December 9, 2019; Washington Post

A “confidential trove of government documents…reveals that senior US officials failed to tell the truth about the war in Afghanistan throughout the 18-year campaign, making rosy pronouncements they knew to be false and hiding unmistakable evidence the war had become unwinnable,” writes Craig Whitlock in the Washington Post.

Whitlock’s statement is based on documents released to the Post by the federal government after a three-year legal battle. The documents come from the Office of the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction or “SIGAR,” which interviewed over 600 people starting in 2014 for its “Lessons Learned” project. Since 2016, SIGAR has published seven papers based on research for that project, but the reports, contends Whitlock, often omitted the “harshest and most frank criticisms from the interviews.”

What the Post has received, explains Whitlock, is “more than 2,000 pages of unpublished notes and transcripts from 428 of the interviews, as well as several audio recordings.” Of these 428 interviews, the names were blacked out for 366 of them, although Whitlock indicates that the Post was able to independent able to identify 33 additional names independently. Whitlock adds that the Post is still seeking a court order to remove the remaining name restrictions.

Although the Afghanistan war has received scant US media coverage in recent years, the US commitment in dollars and lives lost has been significant. Today, the US military contingent today in Afghanistan has fallen to 13,000 soldiers, but bombing is occurring at three times the pace that it occurred under President Barack Obama. Civilian deaths in 2018 totaled 3,804, the highest single-year total since the United Nations started counting a decade ago.

Since 2001, Whitlock adds, “more than 775,000 U.S. troops have deployed to Afghanistan, many repeatedly. Of those, 2,300 died there and 20,589 were wounded in action, according to Defense Department figures.” More broadly, an estimated 157,000 have died in Afghanistan since the war began, including an estimated 64,124 members of the Afghanistan security forces, 42,100 Taliban-affiliated fighters, and 43,074 Afghan civilians. Additional fatalities include 3,814 US contractors, 1,145 coalition troops, 424 humanitarian workers, and 67 journalists.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Direct federal costs (defense, state and US Agency for International Development) are estimated to be between $934 billion and $978 billion. Per capita, that works out to about $3,000 per US resident. These figures, adds Whitlock, “do not include money spent by other agencies such as the CIA [Central Intelligence Agency] and the Department of Veterans Affairs, which is responsible for medical care for wounded veterans.”

Among the findings:

- John Sopko, the head of SIGAR, told the Post that the documents show “the American people have constantly been lied to.”

- “Officials who served under Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama said both leaders failed in their most important task as commanders in chief—to devise a clear strategy with concise, attainable objectives.”

- The $133 billion for reconstruction, aid programs and the Afghan security forces, is “adjusted for inflation…more than the United States spent in Western Europe with the Marshall Plan after World War II.”

- A lack of adequate controls meant that “opportunities for bribery and fraud became almost limitless.” Gert Berthold, a forensic accountant who served on a military task force in Afghanistan from 2010 to 2012, indicated that of the 3,000 Defense Department contracts worth $106 billion that he helped analyze, “about 40 percent of the money ended up in the pockets of insurgents, criminal syndicates, or corrupt Afghan officials.”

- According to interviewers, one Norwegian official said that as many as 30 percent of Afghan police recruits had deserted their posts, so they could “set up their own private checkpoints” and extort payments from travelers.

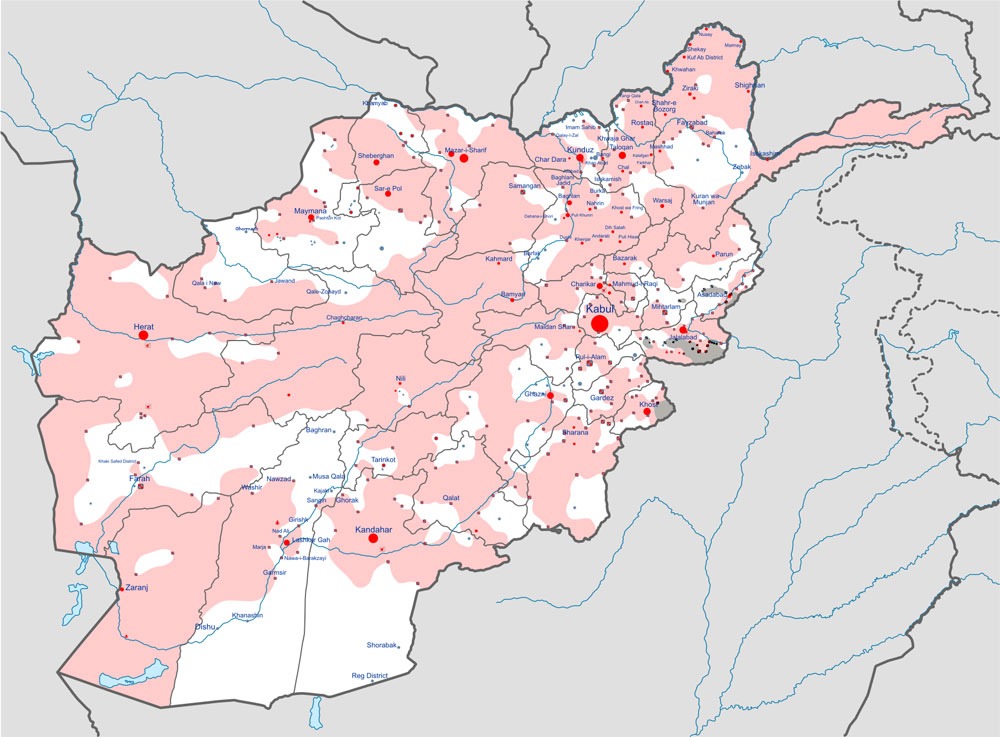

- Afghanistan currently produces 82 percent of the world’s opium supply. “Last year,” Whitlock writes, “Afghan farmers grew poppies—the plant from which opium is extracted to make heroin—on four times as much land as they did in 2002.”

The Post organizes interview transcripts by topic—spin, strategy, nation-building, corruption, security forces, and opium. It has also highlighted 25 of the interviews that Post reporters consider to be particularly essential reading.

What happens next? Two members of the US Senate Armed Services Committee, Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) and Josh Hawley (R-MO) have called for hearings to be held, which may reveal some additional details.

Meanwhile, the Afghanistan Papers remind us of the high cost in lives—and in treasure—of the 18-year-war. For example, if just half of the direct spending on Afghanistan had been redirected to fund universal pre-K education, the federal government could have covered the estimated $26 billion a year cost these past 18 years without raising taxes a penny.—Steve Dubb