November 13, 2018; Washington Post, New York Times, and The Tennessean

It took more than a year—remember the original request for proposals in September 2017?—but the location of Amazon’s second headquarters city is now official. Surprise! It’s actually two cities, with Long Island City in Queens (across the East River from Manhattan) and Crystal City in Arlington (across the Potomac River from Washington, DC) as the “winners.” Amazon’s decision to split its second headquarters, which had been telegraphed last week, means that Seattle will remain the prime company headquarters.

The two locations may give the bookies who took bets on Amazon’s decision some payout math to do. Still, the folks who chose New York City at 60–1 odds probably won’t mind their half-payout. (Crystal City, by contrast, was a heavy favorite, so no big-money winners there.) We’ll see if New York Governor Andrew Cuomo makes good on his pledge to change his first name to “Amazon.”

As expected, Amazon is collecting public subsidies in the process. The amount offered had been a closely guarded secret. Now we know that in New York City, the state and city combined are providing $1.85 billion in tax breaks to the tech giant—about $74,000 per job.

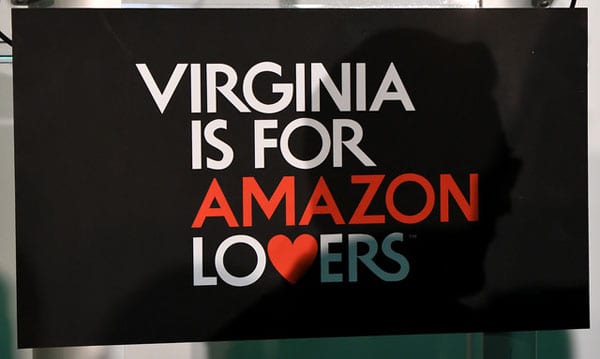

Northern Virginia is also providing significant aid to Amazon. Jonathan O’Connell and Robert McCartney report in the Washington Post direct subsidies totaling $573 million, as well as $223 million for transportation improvements. O’Connell and McCartney add that, “Virginia Tech plans to build a $1 billion graduate campus in Alexandria focused on innovation, part of the higher education package the state offered the company.”

Nashville will house an “Operations Center of Excellence,” which is expected to employ 5,000 people. The center will coordinate customer fulfillment, transportation, supply chain, and other similar activities. Amazon is collecting money from Nashville too. The Tennessean reports Amazon will get “performance-based incentives of up to $102 million.”

But some “losing” cities, which now have the chance to invest in more effective and inclusive homegrown economic development, offered even more. As the New York Times’ Bryce Covert summarizes:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Maryland bid $6.5 billion in tax incentives and another $2 billion in infrastructure upgrades, and its transportation secretary at one point offered the city a “blank check.” Newark, New Jersey, topped that, dangling $7 billion in front of Amazon. Columbus, Ohio, said it would waive all property taxes for 15 years. Chicago offered to let the company pocket between 50 and 100 percent of the income taxes its employees would pay to the city. Fresno, California, proposed giving Amazon joint control over deciding where to spend its taxes.

Times columnist Michael Kimmelman adds that,

Scandalously, American cities and states now spend some $90 billion a year in cash and tax incentives to attract companies, money that could go for infrastructure, schools and police, and that usually doesn’t pay off, as Derek Thompson pointed out this week in The Atlantic. Amazon’s nondisclosure clause set up a process that allowed it, in effect, to crowdsource vast swaths of information about cities while preventing their citizens from knowing what their elected officials were doing to entice the $860 billion company.

Of course, economic development incentives were never expected to be the primary driver of Amazon’s decision. As NPQ noted last January, citing Good Jobs First, state and local taxes are only 1.8 percent of an average company’s tax structure. More factors in Amazon’s decision include the following:

- The existence of footholds in both communities. Karen Weise of the Times notes that “about 1,800 people in advertising, fashion and publishing already work for Amazon in New York, and roughly 2,500 corporate and technical employees work in Northern Virginia and Washington.”

- Personal connections. Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos owns a $23 million mansion in Washington, DC, as well as the Washington Post.

- Easily assembled land. In Crystal City, for instance, the $4.4 billion real estate firm JBG Smith “owns a majority of the property in the bid—enough to accommodate the entire project on its own,” the Post

- The existence of large workforces of highly educated white-collar workers that the firm wants to hire.

Not everyone is pleased to be selected by Amazon. For instance, the Post reports that residents in the “nearby Del Ray neighborhood in Alexandria expressed worry earlier this year that Amazon’s arrival would worsen daily rush-hour backups that already slow traffic to a crawl.” Housing, the Post adds, is also a major concern. The regional council of governments estimated a 65,000-unit shortfall by 2025; Amazon’s arrival makes that gap thousands of units larger.

Meanwhile, nonprofits consider how to respond. In northern Virginia, Anna Scholl, executive director of Progress Virginia, tells the Post, “Thousands of new high-paying jobs could be a boon to our community, but we deserve to know the cost. Tens of thousands of new workers and their families are sure to strain community resources when it comes to affordable housing, mass transit and traffic, and quality local schools. It’s only right that Amazon pay their fair share.”—Steve Dubb