May 30, 2018; Cleveland Plain Dealer

Among the Ponca in Oklahoma, Casey Camp-Horinek has “watched heroin and opiate addiction sweep though…over the past decade,” creating what she calls “walking zombies.” All told, more than 3,000 people are enrolled in the Ponca Tribe of Oklahoma, and opioid addiction rates are high. In many cases, “listening to their doctors” was the primary cause of addiction.

“I think it snuck up on us,” says Camp-Horinek. “I think the fact that you are dealing with something that’s being prescribed by your medical caretaker made us believe that everything would be OK.”

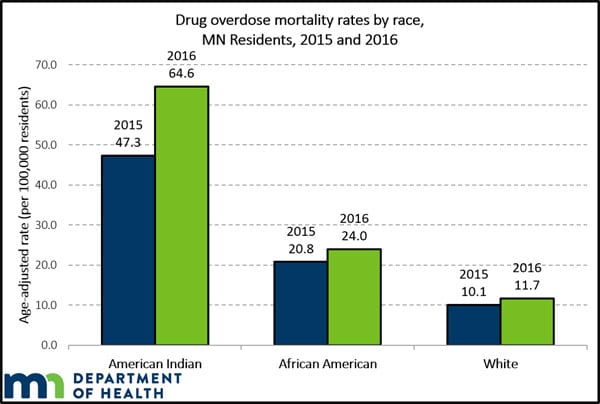

Nationally, as NPQ noted last fall, federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data show that American Indians have a higher rate of overdose deaths from opioids than whites. This past March, Dr. Michael Toedt, Chief Medical Officer of the Indian Health Service, told the US Senate Committee on Indian Affairs that even though CDC data already show that American Indians have the highest rate of opioid addiction–related fatalities, the CDC numbers “may represent an undercount for Native Americans and Alaska Natives by as much as 35 percent, because death certificates often list them as belonging to another race.”

In response, Eric Heisig notes in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, “Native American tribes across the country have filed or are considering filing lawsuits against drug companies over the nation’s opioid epidemic.” In April 2017, the Cherokee were among the first American Indian nations to sue. This March, the Ponca Tribe of Oklahoma, filed their own lawsuit “to recoup costs for social services and other programs…as a means to treating record-high addiction rates among Native Americans.” The Ponca of Nebraska, along with three other American Indian nations—the Winnebago and Omaha tribes in Nebraska and the Santee Sioux Nation—also filed a lawsuit last month.

Additionally, this past January, NPQ covered the filing of a lawsuit by the Rosebud Sioux, Flandreau Santee Sioux, and the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate in the Dakotas. Chairman Dave Flute of the Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate, a nation whose territory straddles the South Dakota-North Dakota line, notes that opioid abuse has grown “to the point of being catastrophic.” Brendan Johnson, a former US attorney who is now working for Robins Kaplan American Indian Law and Policy Group and who is part of the legal team representing the Dakota nations, observes that, “Here the tribes have stood up and demanded to have a voice.” According to the suit filed, 28 percent of patients treated for opioid use disorder in South Dakota were American Indians in 2015–2016, even though they are only nine percent of state residents.

As NPQ has noted, most legal claims filed against opioid manufacturers and distributors are based on at least one of four causes of action:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

- Creating a public nuisance

- Deceptive marketing

- Lax monitoring of suspicious opioid orders

- Unjust enrichment through unfair business practices, leading to unfair windfall profits

A number of the tribal lawsuits, including the one Johnson and his team filed, also highlight the disparate impact the opioid crisis has had on American Indian communities.

As NPQ has noted, in Cleveland, Judge Dan Aaron Polster of the Northern District of Ohio is overseeing hundreds of suits filed across the country. Defendants in the cases include Purdue Pharma, AmerisourceBergen, and the Ohio-based Cardinal Health. Polster has pushed for a settlement, but, adds Heisig, has allowed for discovery and set the first trial for March 2019. The trial date, of course, creates pressure for the parties to reach a settlement before that date.

David Domina, an attorney working with American Indian nations in Nebraska, suggests that the suits brought by the American Indian tribes be treated as their own class. “History, culture, predominant religious practices, significant health practices, abbreviated longevity, lower average user age, elevated usage levels, and historical problems with addictions, all make problems of tribal governments unique.” Johnson adds that American Indians worry about their claims being left out of deliberations, a not unreasonable concern given that they were excluded from the states’ $246-billion, 25-year national tobacco settlement in the 1990s.

The opioid litigation is frequently compared to the lawsuits filed against Big Tobacco. Johnson’s firm Robins Kaplan itself helped the state of Minnesota achieve a $6.13 billion settlement and Blue Cross/Blue Shield $469 million as part of the 1998 tobacco settlement.

As for the opioid cases, Heisig explains that, “The parties have until August 17th to submit a plan to group more cases together for what are called ‘litigation tracks. So far, more than 20 American Indian nations have filed claims, with more claims expected.”

Camp-Horinek calls the drug companies “predators,” adding, “Each and every family I speak to has a personal story about a family member that has become addicted.” Camp-Horinek says any money obtained from opioid litigation would go to fund programs that treat addiction.

Judge Polster said in a May 10th hearing that “the tribes are an important part of this litigation. They have been, I think, disproportionately affected by the opioid epidemic and I’ve made very clear if there is a resolution there won’t be one without them.”

Heisig adds that Paul Hanly, Joe Rice, and Paul Farrell, who serve as lead counsel for the hundreds of plaintiffs in the case, said in a statement that “the tribes are an important component of any solution and we support Judge Polster’s statement that they will not be overlooked nor forgotten. Every plaintiff will eventually have the opportunity to be designated in a case track.”—Steve Dubb