October 30, 2017; Washington Post

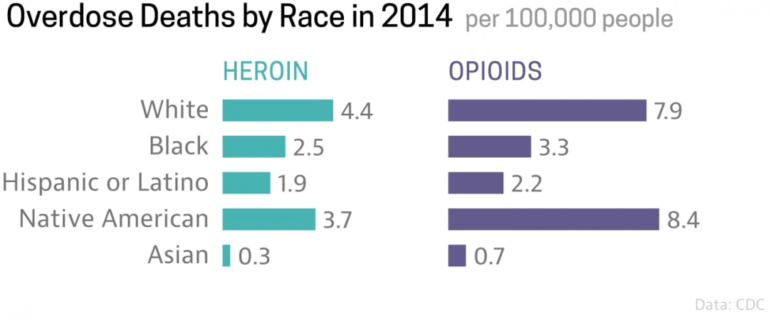

Last week, NPQ wrote about the intersection of the opioid epidemic and philanthropy. Since then, President Trump has declared the opioid epidemic a national public health emergency. Many accounts have emphasized the epidemic’s impact on rural whites—reasonable enough, given that overdose deaths are twice as high per capita for whites as for Blacks and three times higher than for Latinx people. But, as the Washington Post points out, lost in this discussion “is one demographic group that has been profoundly affected by the crisis: Native Americans living on reservations.”

Centers for Disease Control (CDC) data shows that American Indians have heroin overdose rates nearly as high as whites and higher rates of opioid overdose deaths.

There are many reasons why opioids have been so devastating to American Indian communities. One reason, of course, is that the epidemic itself has hit rural America hardest, and most American Indian nations’ lands are in rural areas. But, as the Post points out, intergenerational trauma related to systemic racism is another critical factor.

An article from Stateline, a publication of the Pew Charitable Trusts, emphasizes the legacy of the so-called “Indian schools,” which were “a mid-19th century federal program that attempted to assimilate Native Americans into the rest of the nation’s culture by shipping thousands of Indian children to boarding schools across the country. Many of the children were abused and most lost their cultural identities.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Famously—or, better said, infamously—Col. Richard Henry Pratt, who established the Carlisle Indian School, arguably the best known of the boarding schools, in Carlisle, Pennsylvania in 1879, said their goal was to “Kill the Indian, save the man.” By the 1880s, according to the American Indian Relief Council, “the US operated 60 schools for 6,200 Indian students, including reservation day schools and reservation boarding schools.” A National Public Radio profile in 2008 noted that, “For the tens of thousands of Indians who went to boarding schools, it’s largely remembered as a time of abuse and desecration of culture.”

This may sound like ancient history, but, as the American Indian Relief Council points out, it was only in 1978 that the Indian Child Welfare Act put an end to this practice. Among the congressional findings in the bill was formal recognition that “an alarmingly high percentage of Indian families [had been] broken up by the removal, often unwarranted, of their children from them by nontribal public and private agencies and that an alarmingly high percentage of such children [had been] placed in non-Indian foster and adoptive homes and institutions.”

The Post quotes Gloria Malone, a substance abuse counselor at a reservation-based, long-term recovery house, who said all of her patients “struggle with the brokenness and sorrow of the past.”

A number of Native American communities, such as the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, have taken action. In particular, the Cherokee have sued Walmart, Walgreens, CVS, and drug wholesalers “for knowingly flooding the tribal community with prescription opioids, fueling a deadly drug epidemic that has taken hundreds of lives and cost hundreds of millions of dollars.”

Many American Indian nations have devoted significant resources to improving care for those affected. A few of the examples that the National Congress of American Indians reports follow:

- White Earth Nation has not only successfully engaged law enforcement in decreasing the presence of drugs on the reservation, but they have trained over 100 tribal employees in how to treat overdoses, saving at least 16 lives in the past year. The Nation also has a Maternal Outreach and Mitigation Service, which has already helped 48 mothers, babies, and families with addiction and recovery.

- The Cook Inlet Tribal Council (CITC) Recovery Services department, one of only two detox centers in Alaska, provides treatment to about 850 individuals each year. Services include detox, residential inpatient and outpatient care, screening, assessment, and referral. CITC works with Southcentral Foundation and plans to partner with Knik and Chickaloon tribal organizations and the Mat-Su Health Foundation.

- The Lummi Nation’s Healing Spirit Opioid Treatment Program offers medication assisted treatment, counseling, and accountability through drug testing when treating opioid dependence.

In all of this, there is a determination to prevail in the face of adversity. As a Northern Plains tribal member notes, “There is common agreement that our community’s drug epidemic is rooted in historical and generational trauma. There is also common agreement that, as a tribe, we are strong and resilient and can create support…in order to heal the next generation.”—Steve Dubb