April 24, 2014; CNN

The NGOs that put themselves at risk in the world’s most difficult and dangerous conflict areas are often faith-based, or at least connected to or sponsored by some faith-oriented organization. That doesn’t mean that they are engaged in proselytizing necessarily, but they are living out their faith by providing critical services to people in need. NPQ Newswires have discussed the dangers faced by NGO workers in conflict areas in the past, and another case in point happened in Kabul, where an Afghan guard in charge of protecting staff and patients at a CURE Hospital shot and killed three Americans, including a pediatrician from Chicago.

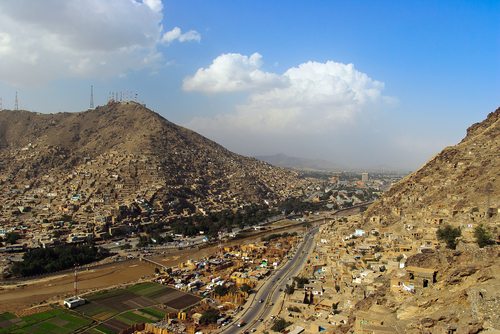

Dr. Jerry Umanos, affiliated with Lawndale Christian Health Center in Chicago, moved to Afghanistan in 2005 to work in a CURE Hospital and a community health center, which supposedly comprise the only two training programs for Afghan doctors. Umanos had felt “called” to move to Afghanistan to treat children and teach doctors. His placement at CURE makes sense; founded by a faith-motivated orthopedist, Dr. Scott Harrison, and his wife Sally Harrison in 1996, CURE has become a network of hospitals and health programs operating in 29 countries, with facilities in Uganda, Ethiopia, Kenya, and other countries in addition to Afghanistan. NGOs like CURE often hire local security forces to provide protection for staff, but situations like this one, where guards turn their weapons against their NGO employers and colleagues, are not unknown.

On one hand, these horrific killings have to be put in perspective. The outrage that has come from some people in this country about the killing of three Americans is justifiable, but those three deaths contrast with the killings of dozens throughout Afghanistan every day, which are treated by many as unavoidable and almost normal. On the other hand, shooting a doctor in a teaching hospital is as callous an action as one could imagine. Dr. Umanos worked for more than seven years at the CURE Hospital. His death means that some number of children won’t be treated and some Afghan medical students won’t receive training. One suspects that he was engaged in the delivery of healthcare, not the evangelism of religion.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The information about the CURE Hospital in Kabul indicates that it has been a locus for many NGOs delivering assistance. With 27 doctors and 64 nurses, the CURE Hospital reports seeing 37,000 patients annually, with an emphasis on children with disabilities, and operates in partnerships with Smile Train (supporting cleft lip and cleft palate surgery), Women’s Hope International (with resources for obstetric fistula surgery), and the Fistula Foundation (training doctors in fistula procedures). The combination of war and poverty plus “stigma, discrimination and misconceived ideas on disability“ conspires to harm children most of all.

It is true, in this context, that the CURE Hospitals include “spiritual ministry” in addition to medical care and training. The definition of CURE’s spiritual ministry is articulated in CURE’s latest fiscal year summary report as follows:

“Often considered cursed, children suffering with physical disabilities, along with their families and communities, come to understand not only the medical reasons behind their children’s physical conditions, but also the reality that God loves and values them, all through the work of CURE. They are all God’s children.”

Consider the subtext of that spiritual statement. In war zones, the number of children with disabilities is huge—not just disabilities related to poverty, but due to injuries from the horrors of war. Unfortunately, in some countries, children and others with disabilities are stigmatized and suffer from all kinds of discrimination, with the disabilities seen as a mark of personal failure or a supernatural curse. CURE’s response to offer treatment, rather than isolation and discrimination, is important and laudable.

If one wanted a reason to object to CURE, the mere presence of religious belief as part of its mission and approach might work, but it’s not a tough religious stance to “proselytize” that we are all God’s children, especially since CURE doesn’t make religious affiliation a requirement for treatment. Perhaps one could point to the presence of Marilyn Quayle (wife of former Vice President Dan Quayle) on the CURE board of directors or the conservative funders among CURE’s sources of support. But give CURE credit: Whatever one might think of its religious background, it is delivering critically important medical services to children with disabilities in a war zone, a place where many others won’t go. If Dr. Umanos and his colleagues were in a nonsectarian organization, they would have still been risking their lives for Afghani children. They didn’t deserve their terrible fates.—Rick Cohen