August 16, 2016, Christian Science Monitor

Lac Seul First Nation is a remote community with about 3,300 residents on the banks of James Bay in Northern Ontario, Canada. They speak Ojibway, Oji-Cree, and English. In this community, one in 15 people has attempted suicide since September 2015. They endured 26 suicide attempts in March 2016. In April 2016, a state of emergency was declared after 11 residents tried to take their lives in a single day.

Widespread poverty, 70 percent unemployment, trauma from Canada’s residential school system, and systemic racism are among the reasons for this collective nightmare.

The Canadian government took Clifford Bull from his parents in Lac Seul at age 7, placing him in a church-run “residential school.” It was part of an official government program to forcibly assimilate children into Western society. Some of Mr. Bull’s peers recall priests washing their mouths out with soap when they spoke their native language. Across Canada, 150,000 children went through these schools, which were notorious for physical and sexual abuse. After six years, Bull dropped out. “When I came home, I didn’t know my culture, I hardly knew my language,” says Bull, who struggled to reconnect with his family and became a teenage alcoholic. “A lot of my life was centered around trying to dull the pain of being abused and traumatized in residential school.”

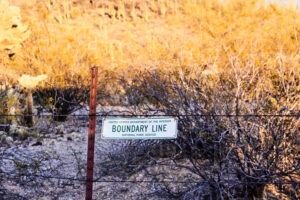

Depravation and assaults on personal dignity loom over the members of this community like specters. The mechanisms of the system that profoundly shape their lives are mostly invisible and inescapable. The educational, healthcare, housing, employment, and criminal justice systems constitute a silent complex that does not lend itself to emotional narrative. Emotions are for the residents of this beleaguered community to attempt to fathom and manage on their own. Each of their life stories involves striving, talent, and connection as well as despair, self-medication, anger, and resignation. Resisting suicide is an act of generosity. As Aristotle wrote in his Nicomachean Ethics, killing oneself is a crime against the community; rejecting suicide helps others choose life as well.

University of Victoria psychology professor Christopher Lalonde has visited scores of remote indigenous communities across Canada while researching cultural continuity. He’s seen reserves with suicide rate that are eight times the Canadian average, as well as communities where suicide is virtually unknown.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“People think suicide happens because of things in the individual’s little life. But suicide is a phenomenon—not on an individual level, but in cultures and communities,” says Professor Lalonde.

Research shows that when one person kills him or herself, the suicide rate in that community spikes. This phenomenon is called “suicidal contagion” or “copycat suicide.” The first suicide normalizes suicide for those who follow. The antidote is to ground young people in their traditions and to help them gain confidence about their future well being. Bull embraced indigenous practices, and his self-esteem slowly rose as he learned the language and hunting skills of his parents and ancestors.

Indigenous people are the fastest-growing segment of Canada’s population and half are under the age of 24, making it more difficult for elders to help everyone who needs it. Other solutions need to be found. “How can we help them construct a healthy sense of identity—something to hold firm and fast, not just in their teen identities but in their lives? That’s not going to come from two health workers parachuted in from Ottawa. We act and react, but we don’t look long-term,” said one of the experts interviewed in the Christian Science Monitor article.

Abominable living conditions can lead to a shared sense of despair, or they can provoke healthy collective protest. Here is a video of a group of activists called Idle No More staging a sit-in at the Toronto offices of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada in solidarity with the people of Lac Seul First Nation.

For Clifford Bull to resist suicide is equivalent to his running into a burning house to rescue those inside who are asleep. By staying among the living, he is saving more than his own life. He is gaining strength measure by measure to be a resource and example for his distressed community.—James Schaffer