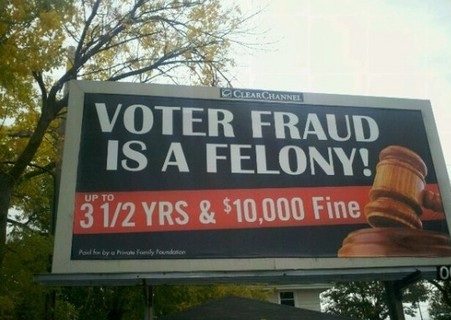

It was recently reported that the Einhorn Family Foundation paid for 85 billboard ads in Milwaukee, Wisc. and 30 apiece in Cleveland and Columbia, Ohio that proclaimed “Voter Fraud is a Felony” and were largely placed in minority neighborhoods. Now comes word that the Einhorn Family Foundation purchased similar billboard ads in Milwaukee in 2010—and received $10,000 that went toward their cost from the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, the nation’s foremost funder of politically conservative charities.

Why bother about a relatively small expenditure of funds by the Bradley Foundation for these signs that occurred in the last election cycle, especially given that the foundation, with assets of more than $560 million dollars, made over $42 million in grants that year? We can think of several reasons.

Disconnect the Dots

The Bradley Foundation is a very competent and well-run foundation, and the Bradley board includes the likes of syndicated columnist George Will, former state senator and losing congressional candidate Tim Considine, well known Princeton University professor and conservative theorist Robby George, and Cleta Mitchell, the Foley and Lardner partner widely considered one of the nation’s top experts in the law of elections, campaign finance, and lobbying. Bradley CEO Michael Grebe was a top lawyer from Foley and Lardner. Grebe told the press that the Bradley grant to Einhorn was for “general purposes,” but acknowledged that it wound up being spent on the billboard ads. The Bradley Foundation’s 2010 annual report describes the purpose of the Einhorn grant as “educational programming.”

Despite the vagaries of “general purposes” and “educational programming,” under IRS regulations on foundations, Bradley is legally required to know precisely what the grant to Einhorn was for. In the Bradley Foundation’s 990PF for 2010, the grant to the Einhorn Family Foundation is accompanied by an asterisk which the foundation used to identify its grants that were covered by IRS “expenditure responsibility” regulations which apply to private foundations that make grants to other private foundations. According to the IRS, “Expenditure responsibility means that the foundation exerts all reasonable efforts and establishes adequate procedures: To see that the grant is spent only for the purpose for which it is made, To obtain full and complete reports from the grantee organization on how the funds are spent, and To make full and detailed reports on the expenditures to the IRS.”

We are not saying that the Bradley grant to Einhorn was illegal, but the way in which the funding was used was certainly odious. This year, Clear Channel took similar billboard ads down after much criticism. Clear Channel, which is owned by Bain Capital, says it pulled the billboards because of a corporate policy against accepting anonymous ads, though it didn’t explain how it decided to approve anonymous billboards that violate its own policy in the first place. Clear Channel also said it offered to keep the billboard ads up if the Einhorn Family Foundation was willing to have its name posted as sponsors of the message but the Einhorns declined. So did the Bradley board give the grant to Einhorn with a thumbs-up for the purpose of the billboard ads, or will they say that, as $10,000 tucked into a $42 million grants budget, they simply weren’t aware of what it would be used for?

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Bradley has been known for its support of conservative think tanks for many years, including the Hudson Institute, the Heritage Foundation, the American Legislative Exchange Council, the Heartland Institute, the American Enterprise Institute, the Manhattan Institute, the Cato Institute, and the Media Research Center, just to name a few. Supporting the development of conservative political thought in this way is well within Bradley’s legitimate scope. Of course, electoral politics is not. In 2010 (and again during this year’s recall election), Grebe, Bradley’s CEO, was also campaign chairman for Scott Walker’s campaign for governor. Steve Einhorn was also a donor to the Walker campaign in 2010 (and, with his wife, an even larger donor to Walker’s effort to fend off his recall earlier this year). Given Grebe’s involvement with the Walker campaign and Bradley, and given Bradley’s funding of the Einhorn Foundation’s 2010 billboards, are we to believe that the ads were not connected to the narrow election of a Republican governor who was seen as unlikely to do particularly well in Milwaukee’s minority neighborhoods?

There is no connection between those dots, according to Grebe, who told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, “We have always maintained strict separation between my personal political involvement and the foundation’s activities, which are not political.”

Why Foundation Leaders and Electoral Politics Shouldn’t Mix

The Bradley Foundation has also been active in its support for combating voter fraud and voter impersonation (which nearly everyone but those who won’t look at the data knows is virtually nonexistent). Bradley’s support is evidenced by its attempt to give a $35,000 grant to True the Vote, an organization which we have written about a few times in the NPQ Newswire (see here and here). True the Vote had to return the money because the organization lacked 501(c)(3) status. Why give True the Vote a grant for election monitoring in 2011? Was Bradley unaware that it and its Tea Party parent organization, the King Street Patriots, lacked 501(c)(3) status, something that could have been determined simply by asking for their IRS letters?

Grebe says that the attempted grant to True the Vote had nothing to do with to the Walker recall campaign. Still, some see a partisan political cast behind the efforts to require voter ID or to “educate” voters about the penalties of voter fraud via anonymous billboards. That impression was perhaps furthered by the comments from a Republican state senator who alleged that former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney would have carried the Badger State had the courts allowed the state’s voter ID law to be implemented in time for Election Day.

The core issue for us, however, is whether a private foundation can legitimately keep its activities separate from a CEO who isn’t simply endorsing and voting for candidates, but taking leadership roles in their campaigns. Even if the Bradley Foundation did nothing wrong, for only $10,000, it has purchased itself a lot more raised eyebrows than the Einhorn billboards were worth. Both conservative and liberal foundations might want to remember that their preferred role is always one that is separate from government so that they can fund the critics and watchdogs of the right and the left to serve as counterweights to government. When foundations get so close to partisan political actors that the wall of separation between philanthropy and electoral aims becomes—or even has the appearance of potentially becoming—blurred or porous, foundations cause themselves, their reputations, and the image of philanthropy damage.

This applies no matter whether foundations are liberal or conservative. Foundations—which are 501(c)(3) entities—are part of the “third sector,” a nonpartisan, albeit opinionated, sector that is different from government and business. If foundations lose that identity—if major, respected foundations act so as to invite questions as to whether they are handmaidens for partisan political campaigns—the damage will extend from the institution involved to the credibility of its philanthropic peers. It takes very little for a private foundation to inflict harm on itself when it pays insufficient attention to its primary philanthropic mission.