A few years ago, I walked into Mil Mundos, a quaint and intimate indie bookstore in Brooklyn dedicated to Spanish and English literature. On the wall below their small cafe area, there was a poster that said, “We are collecting Puerto Rican pesos.” This was the first time I learned that Puerto Rico once had their own currency. It’s taken me a few years to understand that the loss of the currency was only the beginning of the United States’s control of Puerto Rico’s finances up until today.

In seeking to decolonize, Puerto Ricans are creating local projects that experiment with alternative economic models. Valor y Cambio (Value and Change)—a solidarity economy project headed by Frances Negrón-Muntaner, a Columbia University professor—is one example. It consists of a 400-pound refurbished automated teller machine dispensing Puerto Rican peso bills as an artistic nod to community currency. From June to September 2024, a machine dispensing the currency is operating at Poli/Gráfica, a leading Puerto Rican art exhibition, in San Juan. The project calls attention to the ongoing struggle for liberation after over 500 years of financial captivity.

A History of Debt and Colonialism

Before the United States takeover in 1898, Puerto Rico was a colony of Spain for 400 years. It gained ground in 1897, becoming an autonomous state, followed by the Spanish Empire granting a Puerto Rican currency valued equally to the US dollar.

In seeking to decolonize, Puerto Ricans are creating local projects that experiment with alternative economic models.

However, when the Spanish surrendered its colonies to the United States as a consequence of losing the Spanish-American War, the United States banned the peso and started issuing dollars with a significant difference. The Puerto Rican dollar was not equal to the American dollar. It was worth 60 cents to every American dollar and, as a result, Puerto Ricans lost 40 percent of their savings overnight.

Debt is one way in which the United States has retained control over the archipelago, in what is called colonial debts, according to scholars like Rocío Zambrana, who wrote a book with that title. Zambrana contends that “debt functions as a form of coloniality, intensifying race, gender, and class hierarchies in ways that strengthen the colonial relationship between Puerto Rico and the United States.”

Today, debt remains a central challenge of the Puerto Rican economy. In 2015, largely for reasons related to changing US federal policy, Puerto Rico was nearing bankruptcy. In response, a year later, Congress passed the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA), signed by then-President Barack Obama. PROMESA created a bankruptcy process that allowed Puerto Rico to write off some of its debt but at the expense of being subject to the decisions of an oversight board of unelected officials, whose primary interest is to get Puerto Rico to repay the debt to the vulture capitalists and bondholders. This was often through implementing draconian austerity measures, including public school closures that greatly affected the lives of Puerto Rican people.

Puerto Ricans…have long understood that the economic structure in Puerto Rico does not work for them, and never has.

Relatedly, to cover a portion of the government debt, Puerto Rico’s electricity system was privatized in June 2021 and taken over by LUMA, an American-Canadian company. The company has since increased rates—seven times in 2022 alone—with outages continuing. LUMA replaced the public electricity company, Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA), after they filed for bankruptcy that resulted in the write-off of over three quarters of $10 billion in outstanding debt. In 2022, Puerto Rico exited bankruptcy, but the oversight board will remain in place until there are four years of consecutive balanced budgets.

Puerto Ricans Respond

Puerto Ricans, both in the diaspora and on the archipelago, have long understood that the economic structure in Puerto Rico does not work for them, and never has. Many communities have found ways to not depend on the government. A prime example is Casa Pueblo, a community-based organization located in Adjuntas, the central midwestern area of the main island, which, for over two decades, has laid the groundwork for community-owned solar microgrids. After Hurricane Maria in 2017, this grassroots movement became essential as hundreds of homes were left without electricity. Casa Pueblo was able to distribute 14,000 solar lamps and install over 350 solar systems and buildings.

This was one of many community responses to the situation of austerity. Negrón-Muntaner, the Puerto Rican scholar, recalls her own reaction when watching the then-governor of Puerto Rico announce on television that the debt was unpayable: “I think I, along with many other people, immediately had a lot of questions like, how do we get to this point, what happened?”

Soon after hearing this news, Negrón-Muntaner organized a working group to study the debt crisis with the intention of creating a capstone project at the end. In three years, the group spoke at conferences, produced three syllabi to teach students about the debt crisis, and conducted a series of interviews with activists contesting the debt.

A Community Currency Art Project Emerges

During this time, the group realized that the capstone project needed to be a tangible experience for the people affected by the debt, something that wasn’t another conference at a nice retreat. This led to the idea of Valor y Cambio, a community currency that people could temporarily use at local businesses.

The idea of community currencies is not new; indeed, the concept is centuries old. One common US variant is time banking, developed in the 1980s, as a way of giving and receiving services by bartering time. It has often been used as a way to build trust and support networks within communities.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Another example comes from Fortaleza, Brazil, where a community bank was founded in 1998. Managed locally by the Association of Residents of Conjunto Palmeira (Associação dos Moradores do Conjunto Palmeira), the bank produced currency called Palmas, which was equal in value to Brazilian reals—with the aim to create a solidarity economy system that would help to combat poverty by promoting local production and consumption instead of shopping at places like Walmart. As Jared Spears wrote in NPQ, local currencies are “designed to be spent directly in the area. The theory of change involves both encouraging local economic activity—increasing the economic multiplier effect, in technical parlance—while fostering bonds of community.”

Community Currency as a Popular Education Tool

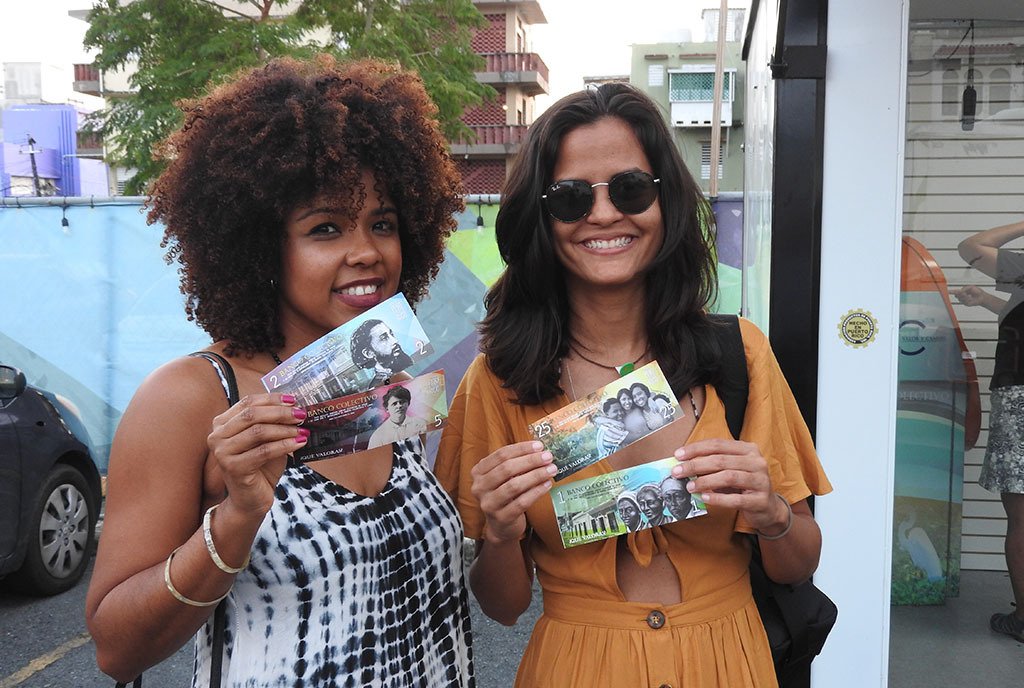

Valor y Cambio is a different project, which Negrón-Muntaner developed in partnership with visual artist, educator, and museologist Sarabel Santos Negrón. The project’s main objective isn’t to institute an alternative currency per se but rather to “plant the seed” for a community currency. To popularize the concept, Puerto Rican pesos in denominations ranging from $1 to $25 are dispensed from an automated teller machine, the bills featuring pictures of Puerto Rican heroes like Roberto Clemente and Julia de Burgos. The bills, co-designed by Negrón-Muntaner and Santos Negrón, each also contain a QR code that tells the story of the person on the bill.

“We wanted to create an experience where people could feel literally in their bodies, in themselves, what it would feel to live in an economy where the basic principle was not extraction, but exchange and sharing,” Negrón-Muntaner explained.

In order to take out money, participants have to answer three questions on the screen: (1) What do you value? (2) What stands in the way of what you value? What obstacles are in the way for what you value to flourish? and (3) Tell us a story about someone or an entity that already does what you value.

In the project’s initial launch in 2019, 42 local businesses, including markets, cafes, and restaurants, mostly in San Juan and some in Humacao, signed on for a 10-day trial period. “We got a surprising number of yeses. I think because people really were open and interested in seeing that another way of organizing the economy is possible,” Negrón-Muntaner observed.

“We wanted to create an experience where people could feel…an economy where the basic principle was not extraction, but exchange and sharing.”

Worried that there would be a shortage of pesos due to high spending, a surprising element of the experiment is that most people didn’t use them. People formed long lines, rain or shine, and waited for hours to use the automated teller machine, but it wasn’t to spend the pesos; it was to collect them.

“I started asking people why they weren’t using them, to which they responded that what the bill represented was a different world not based on extraction, and without racism, gender violence and all the values that the stories held were more important than that we could obtain,” Negrón-Muntaner said.

“We also noticed that when people received the bills from the dispenser, it almost always came with a strong emotion and that emotion was joy. People would cry out of joy, people would laugh. People would be so happy for that moment, and I ended up writing an essay called ‘Decolonial Joy.’ When asked why they were so happy or crying, they would say that this bill represents something that I want to be connected to, or I want to see happen in my life, in my lifetime, and for my children,” she said.

“There was a young Afro-Puerto Rican man who came a lot because he wanted to get the one bill, which was the Cordero family bill and once he got it, he got very emotional, and I asked him why. He said, ‘Because it connects me to my African roots and their teachers,’ and that was invaluable, that experience of connecting to the past and to possibly have this passed onto future generations,” she recalled.

Testing the Currency in New York City

Valor y Cambio was also showcased in two predominantly Puerto Rican neighborhoods in New York City: Loisaida and East Harlem. In New York City, the currency yielded different reactions than in Puerto Rico. Contrary to the deep understanding of the project’s objective and necessity in Puerto Rico, people in New York were interested, but there wasn’t the same emotional connection.

“The idea that we would use community currency and not the dollar for everything was very difficult for people to grasp in New York. While it was very easy for people to grasp in Puerto Rico, the idea that we could build exchange economies or types of economies that didn’t focus on profit was hard for people to embrace or even understand,” Negrón-Muntaner said.

After exhibiting in these two locations, the automated teller machines were moved to Wall Street, the area where Puerto Rico’s debt holders are concentrated. They were met with hostility, disinterest, or complete disregard.

Negrón-Muntaner, alongside the Clemente Soto Vélez Cultural & Educational Center, even experimented with creating a solidarity economy network in New York City called JustXChanges, but it wasn’t tested because the pandemic ensued. “One of the characteristics of successful community currencies is the coherency of our community and clarity of needs. If there’s no need that a currency or a system of just exchange can meet, it’s probably not going to succeed,” she explained.

Expanding Mental Models

Although the effort in New York City fell short, within Puerto Rico the model continues to spread. For example, G-8, a community-based organization composed of eight communities surrounding the Caño Martín Peña Channel in San Juan, created their own currency called los PASOS de Caño. Currently functioning today, they use their currency as a voucher system to recognize the work of community members who help bring G-8 closer to their goals. “I think what we have added to the conversation is a particular framework, a particular way one could do it,” Negrón-Muntaner remarked.

As for Valor y Cambio, in the project’s fifth year, the working group wasn’t able to find funding to continue the project. But Negrón-Muntaner is working on a film and book to document the project and its trajectory. She also plans to donate the peso bills to several archives.

And as Negrón-Muntaner concluded, “I think a lot of people that participated in the project were transformed in some way. There was the idea of what was possible before and then when participating, what seemed possible after, was shifted in you.”