April 4, 2018; Kaiser Health Network

Last month, NPQ reported on a study from the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP) about Atlanta. The study noted, “Atlanta’s growth and its forward-looking political climate have left many communities, especially low-income communities and communities of color, behind.” The public health data back NCRP’s findings up. As Virginia Anderson writes for Kaiser Health Network, among Atlanta’s racial health disparities are the following:

- Atlanta has the widest gap in breast cancer mortality rates between African American women and white women of any US city, with 44 black patients per 100,000 residents dying compared with 20 per 100,000 white women, according to a study in the journal Cancer Epidemiology in 2016.

- It is the city with the nation’s highest death rate for black men with prostate cancer, with a rate of 49.7 deaths per 100,000 residents. The mortality rate for white men there is 19.3, the National Cancer Institute reports.

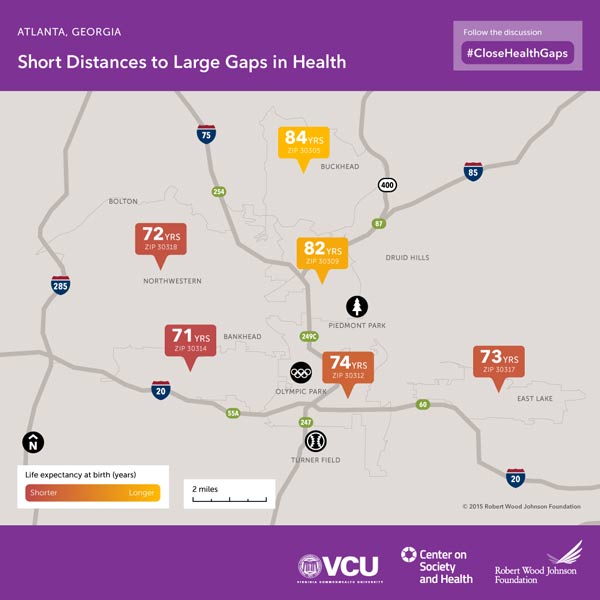

- There’s a 12-year or greater difference in life span among neighborhoods in Fulton County, of which Atlanta is the county seat. Those living in the city’s Bankhead or Northwest neighborhoods, which are predominantly black, fare worse when compared to those who live in affluent, mainly white Buckhead, researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University found.

- Large gaps in mortality exist between African Americans and whites in such diseases as HIV, stroke, and diabetes, according to the Georgia Department of Public Health.

“I think we should be further along in Atlanta, but I think we should be further along in all cities in this country,” says Dr. David Satcher, a former US surgeon general and founding director of the Satcher Health Leadership Institute at Morehouse School of Medicine.

“We have world-class health care facilities in Atlanta, but the challenge is that we’re still seeing worse outcomes” for Blacks, says Kathryn Lawler, executive director of the Atlanta Regional Collaborative for Health Improvement. “Atlanta spends $11 billion on health care in a given year, but much of that is misspent,” she adds.

Atlanta’s situation, of course, is hardly unique. As NPQ has noted regularly, disparate health outcomes are largely the result of what are known as the social determinants of health, with poverty being the largest single factor. As Anderson puts it, “lower incomes, lower levels of education, higher stress, unsafe neighborhoods, lack of insurance and a host of other social factors that combine, over the years, to create differences in quality of health.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Anderson adds that while Blacks “make up just over half of the city’s residents…. 80 percent of Black children…live in neighborhoods with high concentrations of poverty, which often have poor access to quality medical care, while six percent of white children do.” For its part, NCRP noted that since 2000, the number of high-poverty neighborhoods in Atlanta has tripled, even as the city became wealthier.

The stress of racial discrimination itself is also a direct contributor to poorer health outcomes. A 2011 American Journal of Public Health analysis of causes of mortality found that nationally in the year 2000, “The number of deaths attributable to racial segregation is comparable to the number from cerebrovascular disease (167 ,661).”

How to respond? It is notable that NCRP recommendations for philanthropy in Atlanta issued earlier this year and the strategies that leading public health practitioners recommended last year both focus on empowering community groups and fostering a sense of agency. NCRP also emphasizes that philanthropic funding of community groups, to be effective, must be based on a relationship of trust that enables community groups to enjoy long-term operating support.

And there has to be an acknowledgement of the severity of the challenge ahead. As Anderson points out, 50 years after the assassination of Atlanta native son Martin Luther King, Jr., vast inequities remain. Janelle Williams, a Senior Associate for the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Atlanta Civic Site, adds, “We cannot continue to call Atlanta a Black Mecca without first confronting the deep racial inequities that exist.”—Steve Dubb