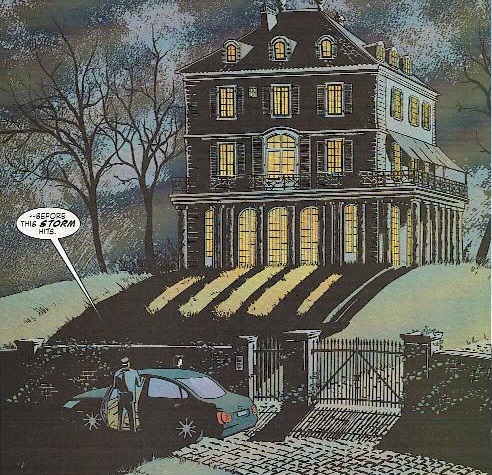

The Unwritten’s Villa Diodati, cometstarmoon

Editor’s Note: This is one of the most beautiful, remarkable, and evocative pieces on the importance of even the most silenced of us staking a claim to defining voice that I have ever read. I, for one, am glad that Letson slipped it past the adjustment team.—Ruth McCambridge

1. The Breaking of Time

“I think poems are echoes of the voices in your head and from your past. Your sisters, your father, your ancestors talking to you and through you. Some of it is primal, some of it is hallucinatory bullshit.”

Paul Beatty, The White Boy Shuffle

Long before I started working on State of the Re:Union (SOTRU), poet Sekou Sundiata told me “one of the biggest issues in America is the country’s collective amnesia.” Our ability to forget whatever didn’t work in the narrative of these United States. We consume the world, and if the bones stick in our craw we spit them out and fly away. In some ways that might be our biggest strength as Americans: the ability to move on, to put one foot in front of the other and face the future. On the surface, it may seem admirable, but moving on without cleaning up just leaves devastation in its wake. Sekou went on to say, “Our selective memory in essence has broken time”—we live only in the present and the acceptable past. Much of Sekou’s life revolved around reclaiming our collective memory.

And yet, time is still broken.

Sekou’s work affected me deeply. After he passed in 2007, I thought a lot about that conversation. How do you “fix” time? That was the idea that was taking up residence in my mind when I first started working in public media. It’s a big question I couldn’t let go of. It’d resurface every few years. I’d write it on walls in my office, scribble thoughts down on napkins in restaurants, talk to myself aloud in public (not recommended). I’d dream about it at night. I read and re-read A Brief History of Time, and any other book about quantum physics I could get my hands on, most of which I still don’t quite understand. In all that searching, the only thing I could come up with was a fanciful idea: where Marty McFly and Doc Brown swoop in with a pimped-out DeLorean and take me back to do some maintenance on the space time continuum. The answer, or my answer, didn’t come from studying the theory of relativity, or my love for 80’s movies. I found it in a comic book.

The Unwritten is an extremely meta book. An evil cabal uses writers to help guide the world into their desired outcome. There’s a bit of magical realism, but mostly it’s about the power of story, how it shapes society and human behavior. Twenty issues into the series, it finally hit me that the answer to the question of “how to fix time?” was already solved. Sekou was the answer to the question he inspired. The poets, the producer, the writers, the storytellers. Public media and other mediums are how we fix time.

2. The Adjustment Team

“I remember you was conflicted, misusing your influence, sometimes I did the same.”

—Kendrick Lamar, “These Walls,” To Pimp a Butterfly

There are many parallels to the world of The Unwritten and ours. Stories have power and resonance and change the way we think and feel, and there is a hidden cabal that uses stories to shape us. They may not be specifically organized with evil intent, but they are, as Philip K. Dick might call them, an Adjustment Team; people whose job it is to set the world on the course they see fit. You can see the fingerprints of their work in our daily lives. Many people in this Adjustment Team don’t even know they are a part of the machine. Every day, the news cycle churns out story after story that builds on a false interpretation of America. They use facts from in the present without following their direct line to the past. Every time a story is told without context it adds to the growing chorus of misunderstanding. If you only look at current events, the issues of police brutality might seem a relatively new thing. The context connects back to the founding of this country and how black people have been treated since the nation’s inception. They stem from slavery, into the Jim Crow era, the fight for civil rights, to the present day. And while it may seem like a heavy burden for a news story to take all this into account, it’s necessary.

If you are examining the uprising in Baltimore, but refuse to acknowledge the crushing generational poverty in that city, and how that poverty was created, then you are doing a disservice to the people crushed by the weight of the system. In fact, you are serving the system, an agent of the Adjustment Team effectively breaking time.

The agents in this Adjustment Team are not bad people. Most don’t even know they’ve joined the bureau. There are no badges, secret handshakes, or decoder rings. You can be diametrically opposed to the concept and still be an agent. I know because I’ve accidentally worked for them on occasion. We strived so hard with SOTRU to be the exact opposite, but sometimes we missed the mark. On a whole, SOTRU bought texture, history, and forethought to the stories we covered, but not all, especially when we first got started. In our first season, we went to the Española Valley in New Mexico. The anchor story in the hour was about acequia, an ancient form of irrigation that has been around for centuries and used in Española to fairly distribute water to farmers. To tell that story, we had to give a quick history of the area. In doing so, we didn’t get into the indigenous population’s struggle with the Spanish colonizers; we went by it so quickly because we needed to move on to the big story. In the edits it didn’t seem like a big deal, but it was a huge mistake, because that conflict shaped the people just as much as the desert climate.

That’s just one example, but I can look back on a few other stories where we missed, and I’m sure there are others that I can’t see. I carry those mistakes to remember, so it doesn’t happen again. There is only one way to fight these adjustments—speak the truth; tell the stories that carry the full weight of the world on their backs. But how? So many news and storytelling organizations want—or at least say they want—to get it right but fail.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

3. The True Face of America

Let America be the dream the dreamers dreamed—

Let it be that great strong land of love

Where never kings connive nor tyrants scheme

That any man be crushed by one above.

—Langston Hughes, “Let America be America Again”

While working on SOTRU for over seven years, I’ve been afforded the opportunity to see the country in a way most people will never get a chance to. It sounds Hallmark-y. Trust me, I’ve tried every way possible to describe it without sounding schmaltzy, but the true face of America is beautiful, flawed, and diverse. Not just in her people, but in her landscape as well.

I think it’s easy to forget, the way we live in our cities, suburbs, rural areas, or wherever become the lens through which we view the rest of the country. In times when that view is disturbed by a news event, we shake our head and think that anyone unlike “us” is crazy. That thought process robs us of the true face of America and feeds a misconception that is at the heart of the rift in time.

The big bang America was born of is a lie we’ve held onto without realizing it. This untruth comes as natural as thinking that water is wet or the sun is hot. At the root of it, we engage in the world that has created a “default human being.” Our understanding of everything comes from the perspective of this mythical “default human,” a straight white male. This default is who we naturally tell stories to, for, and about. The truth is that there is no default human, and there lies the crack in the space-time continuum, the place where our context dissipates, where our history is lost and blind spots proliferate. Stories are told that are incomplete, cultures are discredited because it doesn’t conform, we are a symphony with one instrument playing all the parts. To make the symphony as dynamic as can be, instruments must be given to other players. The experiences, background, and thought process that new people bring into the conversation can be subtle or can completely shift the organization’s trajectory. To a lot of people making decisions on content, that can be scary. But if you want to tell the story right, if you want to “fix time,” it’s fear that must be overcome.

Recently on Reveal, we worked on a piece about George Holliday, the man who filmed the Rodney King beating. In the story, we talked about the unrest that took place in Los Angeles after several of the officers were acquitted. I made it very clear that I was not going to use the word “riots” to talk about the rebellion that took place. It might seem like a small thing, but words matter, they have importance. I cannot in good conscience call a community’s response to brutal oppression a riot. But every day, newsrooms, storytellers, reporters, and producers do. Words like “Riot” or “Thug” have become code words, or as Professor Ian Haney Lopez calls it, a “dog whistle”—an inaudible signal that subconsciously feeds our worst selves. The easiest way to tell if a word is a “dog whistle” is to the look at its use. If a word is only applied to a certain group of people, with negative connotations, then the use of that word is problematic. My colleagues at the Center for Investigative Reporting get it; there wasn’t an argument about it at all. I think part of that has to do with the diversity in the newsroom, and a staff of reporters and producers empowered to speak their minds.

In public media we talk about diversity a lot. So much so, that when it’s brought up, I roll my eyes. Not because I don’t believe in it, but because it’s a buzzword with little weight. I’ve heard the song and dance so much in the past, I no longer get excited when the music comes on. If an organization is talking about diversity, but doesn’t invest in it, what’s the value of all that talk? Public media particularly has done pretty well super-serving the default human being, and it’s understandable—the core audience is what’s keeping the lights on. But we are doing a disservice to both the “core” audience and those outside if we are not presenting America in its Technicolor splendor. The big networks are easy targets when it comes to these issues. The conversation comes up time and time again without any real resolution, but maybe the answer doesn’t come from high up. Maybe it comes from the ground up.

All across the country, the local NPR affiliates are like bundles of nerves. They can tell us when there is pain, they broadcast pleasure, they feel the heat before the fire is visible. But what if those nerves don’t reach into their communities beyond the default households? What if whole swaths of the community don’t know they exist? When I first got into public media, I would tell my friends I had a show on NPR. Most of my white friends understood immediately. But my friends of color—of all economic backgrounds and education levels, from all over the country—had no idea what NPR was. In fact, many still don’t. The question is one of audience, and how do you grow it in communities that are different from your base?

It starts with making people feel welcome. Letting them know they are valued, letting them hear themselves in your local programming. It’s going into these communities physically—being a presence. I heard many stations complaining about Tell Me More going off the air (I complained too!), but I wonder how many of those stations have local shows where people of color are featured? Where that community knows it has a voice? Unfortunately, just putting me on a station’s airwaves does not make that station diverse. What makes a station diverse is the work it puts into the community.

I know firsthand how hard it is to create a diverse staff in public radio. SOTRU operated on a shoestring budget, with an HR department of zero. Every time we hired a producer, we looked for diverse candidates. The demands of the job were very specific, and the pool was really small. It’s a chicken and egg equation. There aren’t many diverse candidates, so diversifying the sound of the station is difficult. Because diverse audiences don’t hear themselves reflected on public radio, they don’t end up going into that field, thus less diverse candidates. Additionally, so many stations across the country are just barely getting by, there are no resources to invest. So when someone says become the “Diversity Genie” and make it happen, it doesn’t seem fair. But throwing up one’s hands isn’t a solution either.

There are efforts afoot throughout public media by stations trying to diversify their sound:

- In Baltimore at WYPR, producer Aaron Henkin teamed up with musician Wendel Patrick and the two started chronicling Baltimore in a series called Out of the Blocks. This type of work paid off when the city was filled with unrest after the death of Freddie Gray. Not only did it serve the core audience, but it expanded it and gave context to the events of the day.

- St. Louis Public Radio did some amazing deep dives in Ferguson, really painting a picture of how to connect to the community you serve.

- KCUR launched an innovative program to bridge the divide.

Podcasting has attracted a whole contingency of people who’ve never heard or worked in public radio, but are in essence making public radio! We shouldn’t be scared to invite them into the tent, in fact we should be rolling out the red carpet. They are young, diverse, and driven. They are our next generation, or they are our replacements.

The world is moving faster than the Adjustment Teams can do their work. Social media is rewriting all the rules, and time will be healed, but only if we join the fight. As media makers, we are vital in that process, because we can tell the story, bring the context, and become the sound that chronicles the fury. The word “public” is our strongest asset. It means while other media outlets’ focus is financial, ours is sacred. It’s a calling; the purpose, to make this country a better place for all of its people. If we do away with the concept of a default human and embrace our humanity in all the forms it manifests, we can make this country what our forefathers dreamed but never actually achieved. We have the airwaves, an abundance of talented, smart people, and a mission. All we need now is the willpower to be who we were always meant to become.

This piece was published in its original form at Transom.org and is printed here with permission.