Even as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to ravage communities across the world, hundreds of thousands of Central Americans remain displaced from their homes. Many have sought asylum in the United States.

On President Joe Biden’s first day in office, he sent the US Citizenship Act of 2021 to Congress. If passed, it could have an impact on Central American migration to the US. While most of the bill focuses on pathways to citizenship, there is a portion targeted at providing aid to Central American countries. Biden’s bill contains funding to “address root causes of migration” in Central America by funding a four-year, $4-billion plan that aims to stem displacement and thereby reduce the flow of refugees to the US.

This begs the question: What circumstances create a refugee? The 1951 Refugee Convention defines the conditions under which the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) continues to apply refugee status: “Someone who is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.” The situation in Central America has already been deemed a refugee crisis by the UN, with close to 900,000 people forced to flee their homes in the Northern Triangle Countries of El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala.

The UNHCR calls the region “one of the most dangerous places on earth.” It is indisputable that the region desperately needs change, but it is not clear how much the US Citizenship Act will improve matters, even if the measure does pass.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The immigration bill put forth seeks to address the widespread problems in Central America that force migration, but the proposed funding should not be seen as benevolence. In fact, the US had a large hand in creating instability in Central America, including its support of a military coup in Honduras in 2009. It’s irresponsible of the US to create a problem, do little to address that problem, and then deny migrants entry or refuge as they flee. In this light, $4 billion for four years is not enough to adequately respond to the crisis. Further, will Central Americans trust the involvement of the US, given the troubled and violent history the US helped shape in the region?

In a four-year report of the region, the Wilson Center found that in order to address the region’s issues, there needs to be “diplomacy, development aid, economic cooperation, strengthening civil society, and security assistance”—all at once. Beyond providing monetary aid, reunification programs for children, and safe and legal pathways to register and process refugee placements, the immigration bill fails to follow this more comprehensive approach.

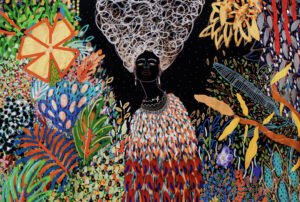

Beyond US policies, nonprofits and similar organizations work in the region to set up peace and anti-poverty programs. For example, the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), a Quaker organization that promotes peace-building worldwide, has programs in Latin America that “focus on issues of urban peace and community security.” In Guatemala, AFSC focuses its efforts on “community accompaniment, generation of information, and advocacy.” AFSC’s three current projects are Micro-Peace Networks, Schools for Peace, and There Are No Barriers for Artivism. Young people’s activism and art is centered in AFSC’s work, and they’re committed to supporting grassroots action and community dialogue.

The central question remains: if Biden’s bill is inadequate, what is the solution? Perhaps partnering with organizations like AFSC could provide qualitative data that shapes solutions moving forward. While Biden’s proposed bill is a step up from the 30-percent decrease in US aid to the region since 2016, much more is needed.—Abby Clauson-Wolf