Consider an economy facing significant economic challenges. The economy is relatively small, geographically isolated, and faces challenging weather that inhibits the growing season, year-round tourism, and in-migration. The population is small, relatively dispersed, and homogenous. In many respects, this economy is in deep trouble, even as a few southern and coastal population centers are faring relatively well.

The above rings true for Maine, where we both live. However, the profile is actually drawn from Finland, circa the late 1980s and early 1990s. The collapse of the Soviet Union, Finland’s largest trading partner, sent the Finnish economy into a tailspin. Unemployment peaked at 18 percent. Finland was at a crossroads: turn inward, or open its economy to the benefits and costs of international trade.

Finland chose the latter option, joining the European Union and becoming an even bigger player in international trade in the high-tech and natural resource sectors. What is less known abroad, but well known in Finland, is that the country simultaneously saw the growth of thousands of new, domestically oriented, cooperatively owned businesses. The growth of Finland’s cooperative economy helped carry the country through turbulent economic times, emphasizing employment, rootedness in community, and creating a balance against the downward pressure on wages associated with international trade (Skurnik and Egerstrom, 2007).

In addition to sharing similar features, Maine and Finland also have considerable differences. What is it about Finland that facilitates a strong cooperative economy? What lessons does Finland provide for Maine—and perhaps other US states that also have rural economies?

Whither the Maine Economy?

As with Finland in the late 20th Century, Maine has a wide spectrum of possible paths that its economy could follow. Here we will focus on three possibilities: 1) maintain the status quo; 2) expand application of traditional community and regional economic development measures; and 3) foster a cooperative economy (Taylor et al., 2016).

Business as Usual

Looking ahead a decade, it is possible that the economic and demographic trends of the past several decades continue. The most challenging factor in this scenario is Maine’s aging population: with the oldest workforce in the nation, the impending baby boomer retirement wave this country faces, dubbed the “Silver Tsunami,” has already crashed upon Maine’s shores.

Meanwhile, continued mechanization and offshoring carries on unabated, leading to fewer and fewer good paying jobs in rural Maine. Too many young people continue to leave. The divergent trajectories of the “Two Maines” continues, with a few southern coastal counties doing okay, while most communities struggle economically and socially, a struggle that has risen to the level of existential threat in numerous rural communities.

Attracting and Fostering Economic Investment

A second scenario focuses on traditional economic development “fixes.” In this scenario, Maine invests in higher education and tax breaks meant to lure businesses. However, these strategies are costly, the benefits flow largely to places doing relatively well in the first place, and the approach leaves Maine jobs and income in a tenuous position, because the firms that were attracted to Maine can just as easily depart anytime thereafter. Additionally, heavy investment in improving education and skills of the workforce, without improved economic opportunity and resilience, can actually accelerate out-migration of those newly educated young people.

Innovations in Ownership: A New Economic Dynamism

Consider a third option, where Maine is well on its way toward a more diversified and equitable economy, with many more sustainable and growing businesses across many sectors and in many communities. The linchpins of this emerging economy are cooperatively-owned businesses: businesses owned by consumers, workers, or groups of producers and independent businesses. Traditional investor-owned firms and family businesses still outnumber these firms in 2030, but the cooperative firms build a foundation for widely shared prosperity in Maine.

The creation of consumer cooperatives provides needed services and jobs in small towns. The opportunity to be a worker-owner of a small business helps retain and attract more qualified, self-directed workers, and turns jobs in a leading state industry, tourism, into lucrative and satisfying career paths for many more Mainers. More young people, low-income people, women, Native Americans and immigrants have the basic knowledge and access to knowledge, resources and assistance to start new cooperatives or convert existing businesses into employee-ownership.

To be clear, developing a cooperative economy is a compliment to, not a replacement of, broadband and other needed public investments. However, widespread adoption of co-ops allows more Mainers to participate in more businesses that generate more wealth and economic security, in ways that are sustainable, equitable, practical, and locally controlled.

Is the third scenario possible? We believe so. While we favor fostering a cooperative economy in Maine, we believe it is important to consider both the opportunities and the challenges.

Co-op Opportunities and Challenges

Co-ops are businesses owned and governed by their members. Co-ops can form as start-ups or by converting from an existing small business. Co-ops fall into a few general categories. Consumer co-ops (e.g. credit unions, food, housing, and electrical co-ops) are owned by people purchasing the firm’s products or services. Worker co-ops are fully owned by workers, while Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs) are businesses where the employees are significant (generally non-voting) shareholders. Businesses form purchasing co-ops to either access inputs they need to operate (e.g. Ace Hardware, Associated Grocers of New England) or to sell products and services they create (e.g. Independent Retailers Shared Services Cooperative, Cabot Creamery or the state’s many lobster co-ops). Multi-stakeholder cooperatives are owned by some combination of workers, consumers and producers (e.g. Fedco Seeds, Maine Farm & Sea Cooperative).

Most co-ops operate under key principles that were first formally articulated in Rochdale, England in the shadow of the excesses of 19th Century industrialization, and later codified by the International Co-operative Alliance: 1) voluntary and open membership, 2) democratic member control (each member gets one vote in governance matters), 3) member economic participation in the cooperative (people invest in the cooperative and profits are shared), 4) autonomy and independence, 5) education, training and information for members, 6) cooperation among cooperatives, and 7) concern for community (International Co-operative Alliance, 2017).

Co-ops help members avoid the monopoly power of a single seller (e.g. a food co-op forming to provide a grocery alternative) and monopsony power of a single buyer (e.g. forest property owners buying a sawmill to avoid “holdup” by an outside mill owner) (Hansmann, 2000). And of course, a “good job” is about a lot more than pay, involving social interaction, a sense of purpose, and autonomy (Schwartz, 2015); employee ownership in particular allows workers to have a much greater voice in shaping workplace policies, benefits and culture.

Co-ops also can make available the benefits of firm creation and ownership to many more people who normally would not think of themselves as entrepreneurs. Usually, entrepreneurship requires large amounts of start-up capital, risk and time. However, by pooling resources, co-ops require lower levels of up-front capital, risk and time from individual members.

Co-ops benefit their local communities in part due to local ownership. Food co-ops have a higher local economic multiplier, make more local purchases, create more jobs per dollar of revenue, create more full-time jobs relative to part-time jobs, and provide better benefits than do conventional grocery stores (ICA Group, 2012).

So, if all of this is the case, why aren’t co-ops more common? One challenge is that having a more diverse ownership can lead to a slower response time, which allows business challenges to escalate into real threats. Second, diverse ownership may lessen the incentives to form new firms (Hansmann, 2000; Dow, 2003). Third, access to capital can be difficult, particularly for co-ops formed by people with limited means.

The second and third challenges can be overcome when a conventional business is converted to cooperative ownership. In this option, founders get rewarded for their efforts in the sale.

The greatest challenge, however, may be one of culture, mindset, and awareness. Neither entrepreneurship nor cooperation (in the sense of ownership) are widely taught, promoted or understood in the US. A successful and sustainable worker co-op, for example, requires a different mindset toward livelihood (Abrams, 2008). However, as Finland and other places show, these obstacles can be overcome.

Broad-Based Ownership in US History

Broad-based ownership models have been a central element in US development. While the US was founded on both the theft of land from Native Americans and Black enslavement, the nation’s founders did perceive widespread ownership of the means of production by white males (land, at the time) as essential for creating a stable, well-functioning republic.

The benefits of ownership were not limited just to land and agriculture: Benjamin Franklin created some of the first co-ops (called mutuals back then, since the term co-op didn’t yet exist), including the nation’s first book library, fire protection services, and a mutual insurance company (Curl, 2012). Maine’s cod fishery often used arrangements whereby fishing seamen shared catch profits and sometimes even owned a share of the fishing vessel (Blasi, et al., 2013).

The greatest period of US co-op growth came in response to the Great Depression. Large swaths of rural America gained access to electricity for the first time through rural electric co-ops. These electric co-ops still service three quarters of the US landmass and 13 percent of the population (National Rural Electric Cooperative Association, 2017). During this period, large-scale, regional co-ops in farming, food production, distribution, and retail grocery stores provided food security for many communities and jobs for many workers.

ESOPs gained federal recognition in 1974 and a 1984 law championed by President Ronald Reagan and Democratic Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill added to federal support. Today, the U.S. has 6,460 companies that are owned in whole or part by ESOPs. These companies employ 10.6 million people. The average worker-owner has an ownership stake that is close to $100,000.

Co-ops in Maine: Today and Tomorrow

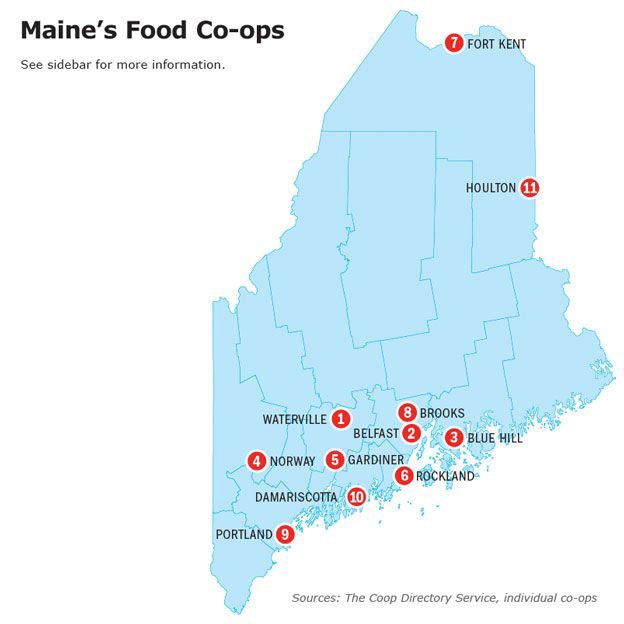

Today, co-ops play an important part in key corners of Maine’s economy. We see the highest potential in six sectors: 1) food, 2) affordable housing, 3) preservation of legacy businesses, 4) forest products, 5) tourism, and 6) craft manufacturing.

With food, dairy co-ops have long been central to that industry. Members of the 21 lobster co-ops pull in over a quarter of the state’s overall catch.2 Co-ops have long played a role in providing processing and distribution infrastructure for food producers. Worker-owned farms, such as New Roots Farm in Lewiston formed by Somali immigrants, can help new farmers more easily start their operations and own their own land by pooling capital and expertise. Meanwhile, as much as 400,000 acres of farmland in Maine will soon change hands (Maine Farmland Trust, 2016) largely due to the age of farmland owners. Co-ops can help preserve these working lands.

Second, many Maine communities face significant housing challenges. Raise-Op Housing Cooperative in Lewiston has purchased some of the community’s large stock of apartment buildings and brought homeownership back to the downtown neighborhoods. In the process, residents are sharing ownership, gaining access to affordable housing, renovating deteriorating buildings, and developing connections among themselves and with the broader community. RaiseOp members range from very low to middle-income families, and include veterans, immigrants, small business owners, single parents, and senior citizens.

Another valuable housing model are Resident-Owned Communities (ROCs), in which manufactured home park residents form co-ops and purchase the parks from investor-owners. Nationally, by July 2020, there were 258 ROCs in 17 states with nearly 17,500 homes. In Maine, ten communities with 464 homes are ROCs. It is worth noting that Maine has over 600 parks that are home to over 30,000 Mainers, so much more could be done to advance this model.3

Third, as noted earlier, Maine has the oldest workforce of any state. Census data indicates that Maine has roughly 32,000 small businesses with employees, which employ over half of our workforce. Of these, 75-80 percent of business owners will want to retire in the near future, but only 17 percent of them have a concrete succession plan. While some family businesses will successfully transition to younger family members, only about 30 percent of those businesses succeed in the second generation (Hilburt-Davis and Green, 2009). Maine’s perpetually anemic economy cannot handle the rapid loss of jobs and economic activity that could come from thousands of business owners closing their doors over the next decade. Conversion to employee ownership could help avert this pending catastrophe. An added bonus is that employee-owned businesses are more productive and profitable, create more jobs, and are less likely to lay off workers in a downturn (Kurtulus and Kruse, 2017).

Employee ownership also can help address two vexing challenges of rural communities – youth retention and attraction, and limited household wealth. One recent study showed that worker-owned firms were much more successful at attracting and retaining young workers and greatly improved their incomes, household wealth and job tenure. Another study showed that lower income workers (particularly workers nearing retirement) in worker-owned firms had dramatically higher household wealth, and employee ownership significantly narrowed the gender and racial wealth gap.

Fourth, in Maine, forestry is a key area of opportunity. The large role played by forestry-related co-ops in Scandinavia and Quebec illustrates their viability. For example, Boisaco, Inc. is a multi-stakeholder industrial co-op owned by hundreds of millworkers, loggers, residents and small business owners in a town of 2,000 people in northern Quebec. The co-op formed to take over a sawmill in 1984 after the facility’s third bankruptcy in 10 years. Desjardins Credit Union provided initial financing backed by the province and, since then, the co-op has invested heavily, diversified its product lines, and now employs over 600 people. Three in ten of its millworkers have served on the firm’s board of directors (Bau, 2012).

Fifth, tourism, an industry not often viewed as the path to steady, high-paying jobs, can change to do so. Through worker ownership, the fast food server, the gardener, and the housekeeper can own shares in companies and be better compensated.

Lastly, co-ops are well-suited to craft manufacturing. While large-scale manufacturing is declining (Moretti, 2012), smaller-scale manufacturing is strong. An example of this is microbrewing: Maine is one of the top five states in microbreweries per capita (Brewers Association, 2017).

For inspiration, Maine could look to the Carolina Textile District (CTD) in rural North Carolina. CTD is a nascent, cooperative network of small-to-medium size textile manufacturers created by Opportunity Threads (a worker-owned, contract cut and sew facility), Burke Development, Inc. (the economic development entity for Burke County), and the Manufacturing Solutions Center (a research and development organization) (Chester, 2015).

Why Co-ops Matter: Back to Finland4

As we noted, Finland offers highly relevant lessons for Maine to consider. However, unlike Maine, Finland ranks near the top of every index of social and economic health as one of the world’s most equitable, educated and prosperous economies.

Finland gets a lot of attention for its excellent education system, its saunas, its achievements in gender equality, and for having the world’s youngest prime minister, but we hear less about its co-ops. And yet, Finland has more co-ops per capita than any other country. More than one in six Finns are employed by co-ops, and more than five in six are members of at least one co-op. As of 2014, over 5,000 co-ops created employment for more than 90,000 workers and generated annual revenues of $40.9 billion.

Co-ops occupy dominant positions in many industries. For example, Valio is a consortium of dairy cooperatives that includes 85 percent of dairy farmers in the country. The S Group, a network of 28 consumer co-ops has 270,000 members and controls 44 percent of the market in daily goods through ownership of hotels, restaurants, gas stations and banks.

And this is no historical artifact. Until the 1990s, Finland’s co-op sector was no larger than that of its Scandinavian cousins and worker co-ops were virtually unknown (Kalmi, 2013). But then co-ops took off: from 1987 to 2006, 2,921 new co-ops were established in Finland, including 696 worker co-ops, 312 marketing co-ops, and 152 publishing and media co-ops. As of 2013, 150 to 200 co-ops are being formed in Finland each year, this in a country with a population of roughly 5.5 million people (less than the population of Massachusetts (Kalmi, 2013).

What explains this growth? First of all, there was established infrastructure, such as The Confederation of Finnish Cooperatives, better known as the Pellervo Society, which was founded in 1899 and had a long history of providing a robust level education, training, technical assistance, financing for developing co-ops. But most critical was economic necessity. The fall of the Soviet Union plunged the country into the worst economic crisis in its history (Hjerppe, 2008). This was Finland’s Great Depression. Finns responded by forming co-ops.

Is Finland’s success “exportable” (Midttun and Witoszek, 2011)? Finland, like the rest of Scandinavia, has a high level of social services backed by high taxes. It also has a much high degree of cultural homogeneity than Maine, to say nothing of other US states.

And yes, you do need a cooperative culture to support a co-op economy. But stereotypes aside, Finland faces its own challenges in this area. (Skurnick and Egerstorm, 2007). First, individualism is valued in Finland just as in the US; indeed, entrepreneurship education is taught in public schools. Second, a recent report by JP Morgan showed Finland and other Nordic countries were just as “business friendly” as the US. Third, Finnish social harmony can be exaggerated; notably, Finland had its own civil war in 1918, fought along class lines, and divisive, at times violent, political and social tensions into the 1960s (Solsten and Meditz, 1988).

Clearly, no one single policy or cultural characteristic ensures co-op success. That said, the following elements seem to help:

- Supportive public policy, including regulatory, tax, financing, and technical assistance

- Knowledgeable and diverse finance institutions

- Strong trade associations engaged in education, promotion, advocacy, technical assistance, and market research and development

- Widespread education programs in cooperative business development and management

Developing a Co-op Ecosystem in Maine

Where co-op ecosystems have developed, there have been impressive results: stronger economies and communities, higher wages, more innovation and entrepreneurship, and less inequality. And the more developed the ecosystem, the more impressive the results.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

There is no single “recipe” to build a co-op ecosystem (Hausmann, et al., 2008). What is critical is intention. That said, here are some elements to consider.

First, state government and the philanthropic sector should make it a priority to develop co-op and employee-owned businesses. Key leverage points could include education and outreach; technical assistance for rural, low-income and immigrant communities; and policy research.

Second, we should encourage the conversion of business assets to co-op or employee ownership and reduce the cost of financing the sale. For example, eight states provide various tax incentives for the sale of manufactured home parks to a resident-owned co-op, and Iowa and Missouri have both implemented a tax exemption of 50 percent on the sale of a business to employees.

Third, we should make sure people can get the information and technical assistance they need to develop a new co-op or pursue a successful conversion. Seven state employee ownership centers exist today. Ohio, for example, has helped over 100 firms with roughly 15,000 employees become employee-owned at a fraction of the cost of traditional jobs programs. To expand resident-owned housing, simply providing residents notification of when a mobile home park is put on the market would help. New Hampshire did this three decades ago and today 30 percent of that state’s mobile home parks are resident-owned.

Fourth, the state can leverage its deposits in local banks that commit to lending to co-op and employee-owned businesses. In Indiana and Ohio, state treasurers purchase special certificates of deposit to create a capital pool for low-interest loans for employee-ownership conversions.

Fifth, entrepreneurship education, training, and mentoring opportunities matter. Every high school student should have opportunities to gain real world business experience.

Sixth, while a co-op ecosystem requires public policy, existing co-ops can be mentors. Building a state association would greatly strengthen the co-op ecosystem and could facilitate partnerships with high schools and community colleges.

Without question, co-op and employee ownership deliver material benefits to and improve the economic health of workers, families, and communities. However, co-ops are uniquely capable of providing greater benefits to us as human beings. Hope, control over one’s future, influence in one’s community, self-reliance and interdependence – these things are in short supply these days in Maine (and around the nation). Building a cooperative economy could make a big difference.

References

Abrams, John. 2008. Companies We Keep: Employee ownership and the business of community and place. Chelsea Green Publishing, White River, VT.

Bau, Margaret. 2012. Boisaco, Inc., a Community Owned Industry in Remote Quebec. USDA Rural Development, Stevens Point, WI.

Blasi, Joseph R., Richard B. Freeman, Chris Mackin, and Douglas L. Kruse. 2008. Creating a Bigger Pie? The Effects of Employee Ownership, Profit Sharing, and Stock Options on Workplace Performance. No. w14230. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Blasi, Joseph R., Richard B. Freeman, and Douglas L. Kruse. 2013. The Citizen’s Share: Putting ownership back into democracy. Yale University Press, New Haven.

Brewers Association. 2017. “Craft Beer Sales & Production Statistics, 2015.” Web site: https://www.brewersassociation.org/statistics/by-state/ [Accessed February 27, 2017].

Chester, Sara. 2015. “Connecting Heritage Assets to Modern Market Demand: Reinventing the Textile Industry and Restoring Community Vitality to Rural North Carolina.” Economic Development Journal 14 (4): 34-40.

Curl, John. 2012. For All the People: Uncovering the Hidden History of Cooperation, Cooperative Movements, and Communalism in America. PM Press, Oakland, CA.

Dow, Gregory K. 2003. Governing the Firm: Workers’ Control in Theory and Practice. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Hansmann, Henry. 2000. The Ownership of Enterprise. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Hausmann, Ricardo, Dani Rodrik, and Andrés Velasco. 2008. “Growth diagnostics.” In Serra, Narcis, and Joseph E. Stiglitz. The Washington Consensus Reconsidered: Towards a New Global Governance, 324-355. Oxford University Press on Demand, Oxford, UK.

Hilburt-Davis, Jane and Judy Green. 2009. Family Businesses Have Traits to Survive. Website: https://www.pbn.com/Family-businesses-have-traits-to-survive,40521 [Accessed March 14, 2017].

Hjerppe, Riitta. 2008. “An Economic History of Finland”. EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples. Website: https://eh.net/encyclopedia/an-economic-history-of-finland/ [Accessed May 14, 2017].

Hoover, Melissa, and Hillary Abell. 2016. The Cooperative Growth Ecosystem. Democracy at Work Institute and Project Equity, New York City.

ICA Group. 2012. Healthy Foods, Healthy Communities: Measuring the Social and Economic Impacts of Food Co-ops. National Cooperative Grocers Association, Iowa City.

International Co-operative Alliance. 2017. Co-operative Identity, Values, and Principles. Website: https://ica.coop/en/whats-co-op/co-operative-identity-values-principles [Accessed March 16, 2017].

Kalmi, Panu. 2013. “Catching a Wave: The Formation of Co-operatives in Finnish Regions.” Small Business Economics 41(1): 295-313.

Kurtulus, Fidan Ana and Douglas L. Kruse. 2017. How Did Employee Ownership Firms Weather the Last Two Recessions? Employee Ownership, Employment Stability, and Firm Survival in the United States: 1999-2011. W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, Kalamazoo, MI.

Logue, John, and Jacquelyn S. Yates. 2006. “Cooperatives, Worker-owned Enterprises, Productivity and the International Labor Organization.” Economic and Industrial Democracy 27(4): 686-690.

Maine Farmland Trust. 2016. Farmland Access. Web site: https://www.mainefarmlandtrust.org/farmland-access-new [Accessed March 13, 2017].

Majee, Wilson, and Ann Hoyt. 2011. “Cooperatives and Community Development: A Perspective on the Use of Cooperatives in Development.” Journal of Community Practice 19(1): 48-61.

Midttun, Atle and Nina Witoszek. 2011. “Introduction: The Nordic Model – How Sustainable and Exportable Is It?” In Atle Midttun and Nina Witoscek, The Nordic Model – Is It Sustainable and Eportable? Norwegian School of Management and University of Oslo, Oslo.

Moretti, Enrico. 2012. The New Geography of Jobs. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston.

National Center for Employee Ownership. 2019. Employee Ownership by the Numbers. National Center For Employee Ownership, Oakland, CA, https://www.nceo.org/articles/employee-ownership-by-the-numbers [accessed Feb. 21, 2020].

National Rural Electric Cooperative Association. 2017. America’s Electric Cooperatives: 2017 Fact Sheet. Website: https://www.electric.coop/electric-cooperative-fact-sheet/ [Accessed May 30, 2017].

Pellervo. 2014. Cooperation in Finland. Website: https://www.slideshare.net/pellervo/ cooperation-in-finland-2012-14261413 [Accessed March 14, 2017].

Restakis, John. 2010. Humanizing the Economy: Co-operatives in the Age of Capital. New Society Publishers, Vancouver, BC.

Schwarz, Barry. 2015. Why We Work. Simon and Schuster, New York City.

Skurnik, Samuli and Lee Egerstrom. 2007. “The Evolving Finnish Economic Model: How Cooperatives Serve as “Globalisation Insurance.’” Presented at Co-operatives and Innovation: Influencing the Social Economy, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

Solsten, Eric, and Sandra W. Meditz. 1988. Area Handbook Series: Finland: A Country Study. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Taylor, Davis F., and Chad R. Miller. 2010. “Rethinking local business clusters: the case of food clusters for promoting community development.” Community Development 41.1: 108-120.

Taylor, Davis, Rob Brown, Jonah Fertig, Noemi Giszpenc, Kate Harris, and Ahri Tallon. 2016. Cooperatives Build a Better Maine. Cooperative Development Institute, Northampton, MA.

End Notes

- Significant portions of this article are extracted from an academic paper written by the authors. See Davis Taylor and Rob Brown, Owning Maine’s Future: Fostering a Cooperative Economy in Maine.” Maine Policy Review, volume 26, number 1, 2017: pages 23 -34, https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mpr/vol26/iss1/5.

- Percentage catch based on author calculations using data from Maine Department of Marine Resources.

- National data on ROCs comes from ROC-USA. See Sammi Chickering, “Austin Community is Second ROC in Texas,” July 1, 2020, https://rocusa.org/news/austin-community/, accessed July 21, 2020. Maine data on ROCs were compiled by the authors based on technical assistance provided by the Cooperative Development Institute. Maine data on mobile home parks was compiled by the authors based on Maine state licensing records.

- This case study, including cited data, is drawn from Pellervo, 2014, except where noted.