January 14, 2020; Vox

“Are there billions of dollars meant to go to charity that really are just sitting there, untouched and collecting dust, in secretive tax shelters?” That is the provocative question that Theodore Schleifer opens with in Vox, where he discusses a California bill, which, if passed, would begin to provide data that would let Californians at least find out just how many inactive DAF accounts may exist.

As Schleifer explains, “The proposal would disclose the ‘payout rates,’ or details about how often DAF accounts are sitting on money for charity but not awarding it. This disclosure is necessary to provide some of the first hard data that could settle the unsubstantiated allegations flowing on both sides of the debate.”

NPQ has written regularly about donor-advised funds, better known as DAFs. A year-and-a-half ago, we ran a series of articles on DAFs. And we first profiled the California bill, Assembly Bill 1712 (AB 1712) last March, which passed through committee this week on an 8–2 vote.

AB 1712 has some legs behind it. Importantly, it has the backing of CalNonprofits, a leading statewide nonprofit advocacy group. As NPQ’s Ruth McCambridge noted at the time of the bill’s introduction, “In NPQ’s experience, it’s very unusual for an association of nonprofits to back a call for regulation of a funding source, but CalNonprofits has done its homework in terms of gauging the interest of its constituency on the issue. A recent survey of 424 California nonprofits indicates that its membership, 70 percent of which have themselves received gifts through a DAF, overwhelmingly believe DAFs are ‘good but need to be regulated’.”

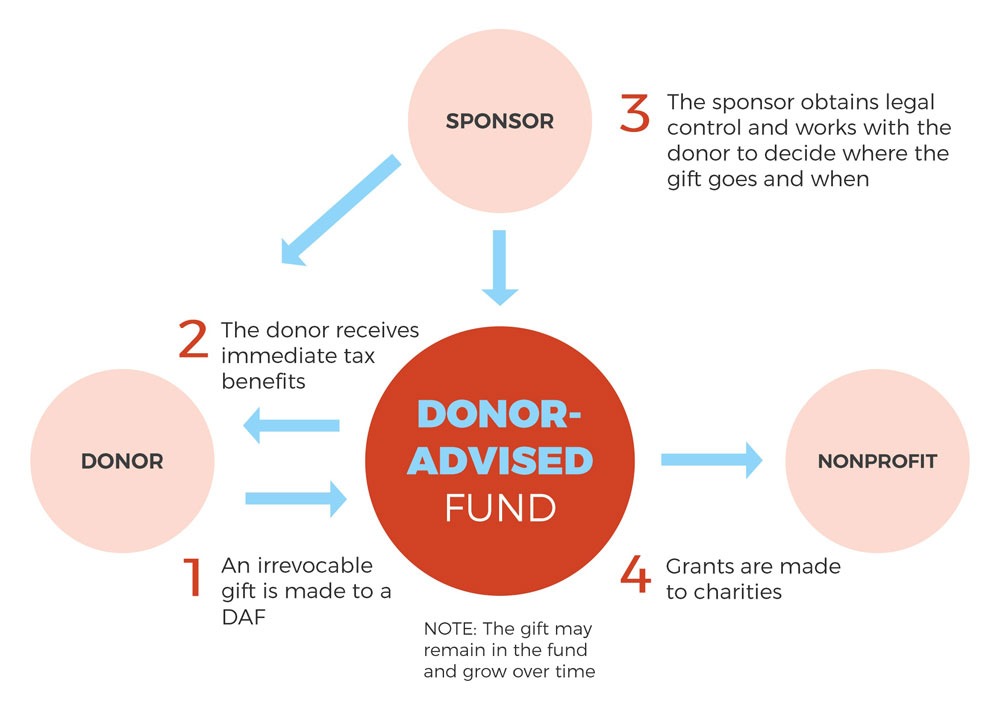

The attraction of donor-advised funds is obvious. As NPQ explained back in 2017:

Essentially, a donor-advised fund is kind of like a charitable savings account. As a donor, you deposit funds into a 501c3 intermediary and, because the intermediary itself is a charity, you get to claim your tax deduction the year of your donation. This buys you time to make decisions about which nonprofits to support, rather than being rushed by the calendar at year-end. And, unlike a private foundation, you don’t have to manage the money yourself.

In general, most DAF account holders use the process appropriately, meaning the money does make it fairly quickly to charities. According to the National Philanthropic Trust, in 2017, there were $112.1 billion in DAFs and in 2018, $23.42 billion in donations was made from those DAFs, so that works out to a 20.9 percent payout rate—meaning, on average, the money gets disbursed to nonprofits in five years.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

But, as Schleifer points out, “Sure, maybe the average donor is consistently paying out their ‘charitable checking account’ to charity, but couldn’t there still be some bad apples who shouldn’t be allowed to cheat the US taxpayer and nonprofit world?”

Well, it is hard to know beyond anecdotes if you don’t have data. As Schleifer observes, “Individual DAF accounts aren’t legally required to disclose their payout rate or to disburse any of the money,” so the potential for abuse is clearly there. And once the tax exemption has been taken, which it is when the original account is established, the public has an interest. It has essentially spent tax dollars by forgiving them.

Then there’s the loophole where foundations can make payouts to DAFs and count that as part of their federally required five-percent payout. Last month, NPQ wrote about one such involving Larry Page, cofounder of Google, noting that Page, “worth $65.1 billion, has been making yearly mega-gifts to his own foundation, receiving tax breaks for his largesse. But when it comes to paying out the five percent in grants the laws require, no deal.…Page controls at least $750 million in donor-advised funds that should already have been spent out.”

The bill, Schleifer cautions, is “still far from becoming a law.” Among the opponents of the legislation is the Silicon Valley Community Foundation, the nation’s largest community foundation, with $8.9 billion in assets as of 2018. Nonetheless, Schleifer notes that if the bill does pass, “the measure could establish a national model for DAFs.” At a minimum, in the form of anonymized data, it would let the public know, not just the average payout rate, but the range of payouts, as well as the percentage of accounts with zero payouts.

This kind of data, of course, could lead to further rules down the road. NPQ has covered various proposals that would set minimum payout rates, and the issue is very much a live one in California.

“We don’t regulate the average behavior. We regulate extreme behavior,” one advocate, Brian Mittendorf, an accounting professor at Ohio State, told Schleifer last year. Thinking otherwise, Mittendorf, would be like saying, “The average person doesn’t commit crimes, so we don’t need laws on the books.”

The California legislation has now passed one hurdle, but it has many steps to go before it becomes law. With the state’s nonprofit advocacy group on one side of the debate and the state’s largest foundation on the other, we will definitely be following how this political battle plays out.—Steve Dubb