November 23, 2016; ProPublica

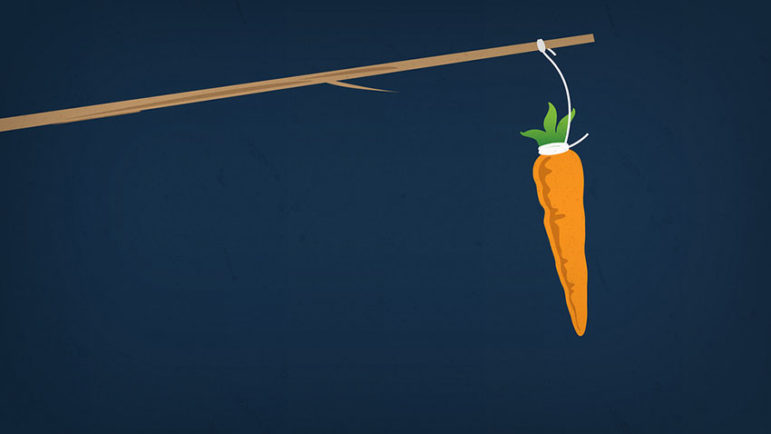

Housing code enforcement traditionally relies on voluntary compliance. That’s because there just aren’t enough inspectors and prosecutors to enforce housing rules. Code enforcement worked for years because “the model” was built around a resident homeowner in a stable neighborhood who had vested interest in repairing her/his home while not aggravating the neighbors. That quaint memory doesn’t reflect today’s typical urban absentee investor, who is too often focused on maximizing profits by minimizing expenses. Preserving asset value and neighborhood goodwill are not compelling interests of most urban landlords. ProPublica asserts that the new model needs to make non-compliance more expensive than compliance and to minimize the cost of bringing an enforcement action. Piling on financial incentives is not the answer.

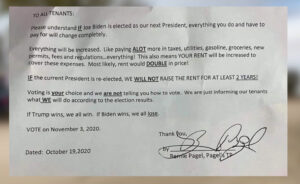

New York City plans to raise the price of non-compliance by clawing back tax benefits given to property owners who promised to keep rents low in exchange for a tax break. Cezary Podkul for ProPublica reports on a new policy focused on landlords who fail to comply with rent restrictions.

New York City housing and finance officials will notify 3,000 landlords next week that they will lose a lucrative property tax break unless they follow procedures aimed at limiting rent increases. The move, which would primarily affect owners of smaller buildings, marks a sharp departure from a previous policy of giving away the benefit without ensuring compliance.

The current non-enforcement policy has made city officials the target of complaints by tenants who were promised affordable rents.

In Rooflines, Professor Paula Franzese calls attention to New Jersey’s failure to withhold incentive payments to landlords who violate tenants’ rights and fail to provide safe and decent conditions. In her article “Stop subsidizing bad landlords,” Dr. Franzese describes a study done by her students at Seton Hall University School of Law: “Today, even the most egregiously derelict landlord is assured a steady and uninterrupted governmental cash flow in the form of substantial rent subsidies no matter the tenant’s assertion in court that the premises are grossly substandard or worse, unlivable.” Her article is a plea for more cooperation among inspectors, courts, and tenants seeking help with poor conditions.

Both of these cases show how cities could make “voluntary compliance” work better with a credible threat of substantial penalties, but the cost of enforcement is still high. Both of these instances require the coordination of three agencies or branches of government—and tenants—in order to succeed.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

This summer in Seattle, the City Council took a different approach, enacting an ordinance that promised “no rent increase for non-compliant units.” Under the Seattle approach, tenants are empowered to challenge rent increases where landlords have failed to comply with housing code requirements.

The novel idea, though, likely won’t restrain rising rents. Rather, it will achieve something that is equally elusive in many major cities: It will force more landlords to fix up neglected properties.

Will the promise of stopping a rent increase be incentive enough to encourage a tenant to risk retaliation by blowing the whistle on a non-compliant landlord? Will Seattle landlords resort to harassment tactics to force these tenants to move, as is common in New York City? Time will tell. In cities like Boston, there is no clear way to measure the scope of the problem. There is no data on the extent of displacement caused by evictions other than the few cases that are contested in housing court.

At a meeting in Cleveland this past week, the Director of Building and Housing was explaining to a group of housing advocates that ramping up a new rental registry program will take several years because landlords aren’t accustomed to applying for a rental license and having an inspection. Besides “jawboning” landlords into compliance, the director suggested that someone in the department could look at the eviction court records, compare the addresses to the rental registry, and then “go after” the unregistered units. But that approach would require a city employee to do data matching, another to send out violation notices, and a law department employee to prepare a complaint when the landlord doesn’t pay the $40 registration fee within a “reasonable time.” In the worst case, a city attorney would need to appear in court to present the case to the judge.

One advocate asked, “Why not make a rule—no registration, no eviction?” The director of Building and Housing was shocked. He told the group that the city didn’t have that authority, but everyone else at the table wondered “Why not?”

It seems like government is accustomed to giving valuable “carrots” in the form of property tax breaks, rental subsidy payments, and summary evictions without having “sticks” that promote voluntary compliance with rules and laws that protect tenants. At the same time, when the cost of enforcement outweighs the financial benefit to the city, renters are left to fend for themselves. The system cries out for market-driven remedies which promote private and public enforcement of housing rights without fear of retaliation in the form of eviction, rent increase, or harassment.—Spencer Wells