The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released its analysis of the budgetary effects of the American Health Care Act (AHCA) legislation introduced in the House of Representatives last week. The CBO analysis, also known as “scoring,” examines federal revenues and expenditures as well as the bill’s effects on numbers of people insured and the cost of insurance. The news isn’t as bad as was feared, but it’s bad enough to build Congressional opposition from both the political right and left.

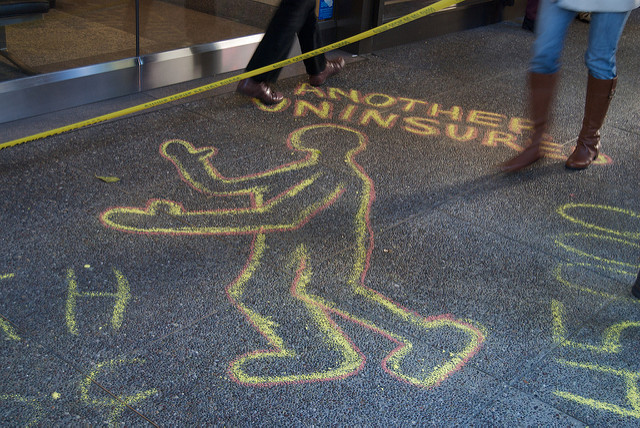

Overall, the AHCA (bill text) will save the federal government about $337 billion over 10 years, mainly by curtailing Medicaid expansion, changing how federal Medicaid funds are allocated to states, and eliminating the current Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) individual and business insurance mandates. Federal taxes are estimated be reduced by $883 billion and spending reduced by $1.2 trillion. CBO predicts that the number of uninsured people under the AHCA will double over the next ten years relative to the number uninsured under the ACA, with a disproportionate of the newly uninsured being those aged 50 to 64 with incomes at 200 percent of the federal poverty level or less. Currently, about 10 percent of the U.S. population is uninsured; under the AHCA, that number will increase to between 15 to 19 percent by 2026. In other words, CBO estimates in 2026 Obamacare would leave 28 million people uninsured; the AHCA would leave 58 million people uninsured.

Insurance costs would increase between 15 and 20 percent from 2017 to 2020 relative to ACA-based estimates, but after 2020 the AHCA’s tax credit-based individual incentives and greater latitude for insurance companies to diversify product offerings (including the return of stripped-down coverage options and increased use of the much-touted Health Savings Account, or HSA) are forecast to make insurance 10 percent less costly than it would be under the ACA.

Major provisions of the American Health Care Act (AHCA) include:

- Eliminating penalties associated with the requirements that most people obtain health insurance coverage and that large employers offer their employees coverage that meets specified standards.

- Reducing the federal matching rate for adults made eligible for Medicaid by the ACA to equal the rate for other enrollees in the state, beginning in 2020.

- Capping the growth in per-enrollee payments for most Medicaid beneficiaries to no more than the medical care component of the consumer price index starting in 2020.

- Repealing current-law subsidies for health insurance coverage obtained through the nongroup market—which include refundable tax credits for premium assistance and subsidies to reduce cost-sharing payments—as well as the Basic Health Program, beginning in 2020.

- Creating a new refundable tax credit for health insurance coverage purchased through the nongroup market beginning in 2020.

- Appropriating funding for grants to states through the Patient and State Stability Fund beginning in 2018.

- Relaxing the current-law requirement that prevents insurers from charging older people premiums that are more than three times larger than the premiums charged to younger people in the nongroup and small-group markets. Unless a state sets a different limit, the legislation would allow insurers to charge older people five times more than younger ones, beginning in 2018.

- Removing the requirement, beginning in 2020, that insurers who offer plans in the nongroup and small-group markets generally must offer plans that cover at least 60 percent of the cost of covered benefits.

- Requiring insurers to apply a 30 percent surcharge on premiums for people who enroll in insurance in the nongroup or small-group markets if they have been uninsured for more than 63 days within the past year.

Other parts of the legislation would repeal or delay many of the changes the ACA made to the Internal Revenue Code that were not directly related to the law’s insurance coverage provisions. Those with the largest budgetary effects include:

- Repealing the surtax on certain high-income taxpayers’ net investment income;

- Repealing the increase in the Hospital Insurance payroll tax rate for certain high-income taxpayers;

- Repealing the annual fee on health insurance providers; and

- Delaying when the excise tax imposed

To cushion the impact on health care providers and insurers, so-called “disproportionate share hospitals” that serve large numbers of uninsured and Medicare patients will see cuts in federal subsidies under the ACA restored by the AHCA. The CBO report states: “The cuts are currently scheduled to be $2 billion in 2018 and to increase each year until they reach $8 billion in 2024 and 2025.” In addition, community health centers would receive an additional $422 million, or 4.2 percent in additional funding, for 2017. So-called “patient and state stability fund grants” will provide $10 billion a year in federal funding between 2018 and 2026 “for a variety of purposes,” including subsidizing the cost of insuring high-risk, high-usage patients in the individual market.

Under this plan, as was expected, Planned Parenthood has been targeted for federal defunding.,. Curiously, CBO interprets the defunding as happening for only “a one-year period following enactment” rather than the expected GOP effort to pass a permanent ban on Medicaid reimbursement to Planned Parenthood clinics. It is a bit odd to look strictly at the financial impact of such a move, but according to the CBO, this provision, if enacted, would save the federal government $178 million in 2017 and a total of $234 million over ten years. However, by CBO’s estimates, in the one-year period in which federal funds for Planned Parenthood would be prohibited under the legislation, the number of births in the Medicaid program would increase by several thousand, increasing direct spending for Medicaid by $21 million in 2017 and by $77 million over the 2017–2026 period.

The legislation would eliminate those cuts for states that have not expanded Medicaid under the ACA starting in 2018 and for the remaining states starting in 2020, boosting outlays by $31 billion over the next 10 years.” States that did not expand Medicaid will also benefit from $2 billion annually from 2018 to 2021, essentially providing federal funding analogous to that already received by states that chose to expand Medicaid without the coverage expansion requirement.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Other Medicaid-related provisions include:

- Requiring states to treat lottery winnings and certain other income as income for purposes of determining eligibility;

- Decreasing the period when Medicaid benefits may be covered retroactively from up to three months before a recipient’s application to the first of the month in which a recipient makes an application;

- Eliminating federal payments to states for Medicaid services provided to applicants who did not provide satisfactory evidence of citizenship or nationality during a reasonable opportunity period; and

- Eliminating states’ option to increase the amount of allowable home equity from $500,000 to $750,000 for individuals applying for Medicaid coverage of long-term services and supports.

The AHCA, introduced by House Republicans and hurriedly passed out of two House committees last week, is the first of three phases of Obamacare “repeal and replace” envisioned by House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI). Not intended to be standalone or comprehensive, the AHCA is envisioned to be included in the Senate filibuster-proof annual budget reconciliation bill as the first phase. The second phase is large regulatory, with HHS Secretary Tom Price leading the effort to “stabilize the health insurance market, increase choices, and lower costs.” The third phase includes other legislation, such as that required to allow health insurance companies to sell policies across state lines and permit groups of small businesses to seek employee coverage as a single unit—both strategies envisioned to reduce premium costs.

CBO addresses “uncertainty surrounding the estimates” this way:

The ways in which federal agencies, states, insurers, employers, individuals, doctors, hospitals, and other affected parties would respond to the changes made by the legislation are all difficult to predict, so the estimates in this report are uncertain. But CBO and JCT have endeavored to develop estimates that are in the middle of the distribution of potential outcomes.

In other words, we’ve done our best to be reasonable, but who really knows for sure about any of this stuff?

Democrats weren’t about to go along with any GOP plans to repeal and replace Obamacare, and the CBO report will give plenty of additional ammunition with which to attack the AHCA. Members of the conservative House Freedom Caucus might also oppose the bill, giving it no chance of passing the House, much less reaching the Senate where Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY) has already introduced his own conservative/libertarian alternative legislation. One news report speculates that the bill might die as soon as Thursday after the House Budget Committee, which includes three Freedom Caucus members, reviews it. “At least seven Republican members of the Budget Committee have made public statements in the past week indicating they want a full repeal of Obamacare, but it’s unclear whether four of them will decide to go out on a limb and vote no [on the AHCA].” If four Republicans join all committee Democrats to vote against the bill, it will fail. Watch for intense lobbying of conservative GOP committee members this week with a goal to have the bill reach the House floor.

President Trump is generally supportive of the AHCA, which reflects much of the developmental work done over the past two years by former surgeon and Rep. Tom Price (R-GA), who now heads HHS. However, Trump has repeatedly said that one of his healthcare goals is to ensure that everyone has health insurance. The CBO saying that the number of uninsured will double under the AHCA is not good news for the administration as it negotiates for the bill’s passage.