Editor’s Note: This article contains sidebars and graphics not available in the digital edition. Please order a reprint to view the full article.

The tv series I Shouldn’t Be Alive tells the stories of people who miraculously survived near-death experiences in remote, unforgiving environments. I would like to see an episode about nonprofit organizations that have survived existential crises. This article tells the story of one such survivor, which reorganized after filing Chapter 11 bankruptcy. It also explains the mechanics of bankruptcy and how to determine whether Chapter 11 bankruptcy can work for other nonprofits. Of course, this article should not be construed as offering legal advice; retain a lawyer for that. Nonprofits have an aversion to using bankruptcy as a tool. While nonprofit organizations constitute 30 percent of all corporations, they represent only 1 percent of corporate bankruptcy cases. I suspect the gap is indicative of their morality rather than their durability. Nonprofits are so anxious about reputation that they prefer risking liquidation to admitting financial distress. But consider the organization described in this article as an example of the opposite conclusion: after it reorganized under Chapter 11, the nonprofit experienced no reduction in gifts, grants, or contracts. The lesson is this: nonprofits should get over the stigma of bankruptcy and do whatever it takes to keep serving their communities.

Digging a Financial Hole at Helping Hand

Helping Hand was a social-service and job training agency with a history of management problems.[1] Ten years prior, it foolishly accepted a gift of real estate that was contaminated with toxic chemicals, setting in motion lengthy litigation over cleanup costs. The CEO and CFO who made the fateful decision to accept the property went to jail for skimming from sales of other donated assets. Later, Helping Hand paid too much for its building headquarters, which was too big for its needs and drained its resources. The COO was married to the CFO, making financial control impossible. There is more, but you get the idea.

When Helping Hand began to hemorrhage money, the board hired a fundraising consultant. The consultant’s plan was never implemented because a key facet called on board members to raise money. The board tried to find a merger partner but failed because pending lawsuits posed liability questions on top of a huge backlog of unpaid bills. United Way notified Helping Hand that it was in danger of losing its annual grant because its finances did not meet acceptable standards. Meanwhile, unbeknownst to the board, the CEO and CFO suspended monthly payment of payroll taxes and deposits into employee pension plans despite the fact that this money was being deducted from paychecks.

Distressed nonprofits that do not pay payroll taxes are liable for steep interest and penalties, and without realizing it, they dig themselves into a hole that may become too deep for Chapter 11 rescue. Further, board members may be personally liable for such debts. When an annual audit of Helping Hand revealed unpaid obligations, the board fired the CEO, COO, and CFO, and I was brought in as the interim CEO. By this time, Helping Hand was deep in debt to the government and more than 200 other creditors.

In the for-profit world, creditors can petition a bankruptcy court to liquidate a corporation while it still has sufficient assets to satisfy their claims. Or, if creditors believe that better management can turn the company in arrears around, they may ask the court for permission to take operational control. But the Internal Revenue Code bars a distressed nonprofit’s creditors from initiating proceedings and seizing operational control.

The Road to Chapter 11

Helping Hand’s lawyers recommended that it voluntarily file for reorganization bankruptcy (popularly known as Chapter 11). The immediate effect of initiating a Chapter 11 case is to block creditor lawsuits seeking payment and to suspend those in progress. Utility companies and vendors are barred from suspending service for past debts. Chapter 11 gives organizations breathing space to renegotiate leases, mortgages, and contracts before their terms expire. A Chapter 11 filing can also reduce outstanding indebtedness by court order instead of repayment.

Unfortunately for Helping Hand, taxes could not be reduced through Chapter 11 and the litigation was expensive, so the board hesitated. Legal fees must be paid in full before other claims are paid even in part. Law firms specializing in bankruptcy are few, but many large firms have a bankruptcy practice and can be approached for pro bono services. Helping Hand’s lawyers declined to represent it pro bono, so it searched for alternatives.

A banker on the board offered one of his turnaround specialists pro bono to put together an “assignment for the benefit of creditors,” also known as “composition of debts,” or a “workout.” This procedure attempts to obtain creditor agreement to reduce all debt proportionately, which is the norm in bankruptcy court. But without judicial involvement, voluntary agreement is hard to obtain, especially from secured creditors.

Helping Hand’s bank, which was also the holder of its mortgage, proved uncooperative. Finally, the board had no choice but to file a Chapter 11 petition (i.e., to declare bankruptcy). It was able to obtain pro bono legal services from a firm specializing in bankruptcy litigation.

A bankruptcy judge has the power to discharge an organization’s debts, with certain exceptions. But first, the organization must submit a new business plan that demonstrates it is likely to produce a cash surplus while servicing a reduced debt load. For the court to accept a plan, all creditors must be treated equally, and at least half of them—accounting for at least two-thirds of the debt—must consent by a formal vote. If creditor agreement is not obtained informally before filing, a reorganizing nonprofit runs the risk of having the court appoint a creditors’ committee to help develop a plan. Not only does this procedure take more time, but the law allows a creditors’ committee to hire counsel and auditors—at the organization’s expense. And in case you’re wondering, donors have no standing in bankruptcy court. Helping Hand’s attempt to secure an agreement out of court was not wasted effort, however, because it was a dress rehearsal for presenting a formal reorganization plan to the court. It was able to file a “prepackaged” bankruptcy, or a “prepack.” (This is the tactic Chrysler and GM just used.) When creditors learned that the matter was headed to court, the holdouts quickly agreed to the plan. Previously, they had been uncooperative because they were afraid that, without court supervision, all creditors would not be treated equally and the bank was concerned that federal regulators would look askance at a voluntary write-down. The court-approved deal included replacing 80 percent of the board, which gave it instant credibility with creditors.

Research on for-profit bankruptcies shows liquid organizations have the best shot at restructuring their debt out of court via a workout. Illiquid organizations with large cash flows use prepacks, while illiquid organizations with weak cash flows use Chapter 11 reorganization.[2] These patterns are probably characteristic of nonprofit bankruptcies too.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

When Is Chapter 11 Right?

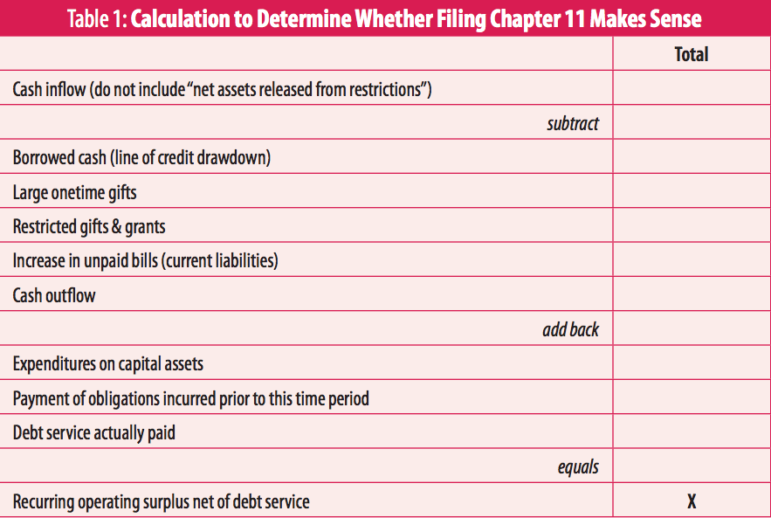

Before an organization jumps headlong into a Chapter 11 filing, it should do a back-of-the envelope calculation to determine whether debt relief might work (for a template, see Table 1 on page 79). The main issue in reorganization is how much debt an organization can service going forward. The object of the calculation in Table 1 is to determine whether the organization without debt could produce recurring cash surpluses. If the number X in the lower-right corner is positive, it is likely that a Chapter 11 filing can restore the organization to financial health without a major change in how it operates.

“Total” is the sum of data from the most recent complete fiscal year plus year-to-date. If the number X is negative, the only way an organization can survive, even by filing Chapter 11, is through a major revision of its business plan, which may involve rethinking mission, types of service, service-delivery methods, and financing.

As Helping Hand’s board considered reorganization bankruptcy, it worried about the reaction of donors and United Way, as well as of government agencies with which it had contracts. But once it faced a choice between filing for Chapter 11 and turning out the lights, it took a candid and aggressive approach with its community partners by seeking their counsel before reorganization and keeping them fully informed during the process.

Helping Hand explained to United Way and donors that its debt load was so heavy that, without using Chapter 11, future funds would be used mostly to retire old debt, not to deliver new services. These donors came to accept that Chapter 11 would reduce Helping Hand’s debt load and allow contributions to be spent on delivering new services. They remained loyal, and there was no substantial reduction in contributions during or after reorganization.

Helping Hand survived independently for a few years after reorganization, but it still had nearly $2 million in tax liabilities that could not be discharged by reorganizing. Although it was able to meet its obligations, its growth prospects were hampered by debt, and it eventually merged with an organization that had initially rejected its overtures. The merger partner agreed to assume the debt because Chapter 11 resolved all the legal issues that had originally scared it away.

Although Helping Hand’s future was touch and go for a while, the story has a happy ending. All distressed nonprofits should consider reorganization bankruptcy. Liquidation is not necessarily the easier or safer course. When the trustees of Wilson College attempted to shut down the institution, alumni persuaded the Pennsylvania attorney general to sue, after which point a judge ordered the school reopened, two trustees removed, and barred the college from paying the trustees’ legal fees.[3]

If Chrysler and General Motors can do it, why can’t nonprofits?

Endnotes

1. For the purposes of this article, the organization studied has been given the pseudonym Helping Hand. Although some facts are on the public record, others are known only to a small group—hence the pseudonym.

2. Sris Chatterjee, Upinder S. Dhillon, and Gabriel G. Ramirez, “Resolution of Financial Distress: Debt Restructurings via Chapter 11, Prepackaged Bankruptcies, and Workouts,” Financial Management vol. 25, no. 1, 1996, 5–18.

3. Alexander V. Zehner, Pa. Ct. Common Pleas, Orphan’s Court Division, 1979. See also, Joseph P. O’Neill and Samuel Barnett, Colleges and Corporate Change: Merger, Bankruptcy and Closure. Princeton: Conference-University Press, 1980.