Chicago’s South Side residents have been fighting for decades against environmental racism from industrial businesses that use their neighborhood of mostly Black and Brown people as a dumping ground. Now, advocates are staging a hunger strike to prevent a new metal-shredder recycling plant that could cause severe lung and heart problems from moving in.

For years, the metal recycling plant from Reserve Management Group’s General Iron Industries has battled environmental regulators in Chicago’s rapidly gentrifying North Side over concerns it was polluting the air, water, and ground. If upscale buyers, renters, and businesses were going to be attracted to the Lincoln Yard $6 billion redevelopment projects that were planned in these neighborhoods, it could not remain.

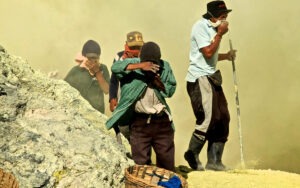

Chicago’s plan to relocate the plant infuriated South Side residents, who say the city sees them as a dumping ground. The neighborhood was once a national economic hub of legendary steel mills and factories, but the environmental costs have been severe. According to a University of Illinois Hospital Community Assessment of Needs (UI-CAN) survey in 2018, children of color on the South and West sides of Chicago were dying from asthma at eight times the rate of their white counterparts. The city’s asthma rate for Black children is twice the national average.

When the plan to relocate the metal-shredder to Chicago’s Southeast Side was announced in 2018, it immediately raised concerns. General Iron had been under investigation by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) three times since 1990. The varied communities of the South Side organized in opposition. Residents voiced their concerns at town hall meetings and through protest actions; they enlisted their elected alders (city councilors) in the fight. But for three years, factory building plans continued.

Earlier this month, on February 4th, community members began a hunger strike, still ongoing, to demand that the city refuse to provide the final licensing that would open the doors and allow metal to be recycled under their noses. At least 77 educators joined the hunger strike during a one-day fast in solidarity. Alder Rossana Rodriguez-Sanchez, who also fasted in solidarity with the strikers for a day, explained to Block Club Chicago, “I’m very familiar with the feeling of being discarded and being used as a dumpster because of environmental racism. I’m incredibly proud that the community is standing up to fight against it—because we have to.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

On day 18 of the hunger strike, advocates seem unmovable, profiling their campaign on social media and calling on Mayor Lori Lightfoot to deny General Iron its permit. A day of action, including a candlelight vigil at City Hall at 5 pm, has been called for tomorrow.

In another effort to stop this move, activists have filed a complaint with the US Department of Housing and Urban Development alleging that moving the recycling plant violates the Fair Housing Act. They are asking the federal government to withhold funding to the city to prevent the relocation from moving forward. Mayor Lightfoot has yet to meet the strikers’ main demand, but her office’s letter to the EPA’s compliance department gives some hope that federal intervention is on the way.

Those who support the move say they trust the operators will meet higher environmental standards and claim the community will benefit from stable and lucrative jobs. Local high school teacher Lauren Bianchi believes her students already recognize these are not the jobs of the future, and told the Chicago Tribune that they “do not see opportunity or a future in this type of industrial development. Many students feel that as adults they will have to move away from the Southeast Side to access jobs and a better quality of life.”

As advocates seek to protect the right to breathe, they stand alongside those protesting biased policing, housing, education, and medical care. Each issue is part of a whole—a struggle to dismantle a web of structural racism and classism.—Martin Levine