May 22, 2018; WBEZ-FM and Chicago Reporter

No matter how great a new idea is, effective planning and implementation are more important. That’s one lesson we can learned from Chicago Public Schools’ (CPS) decision to implement choice-based school reform.

In 2012 and 2013, after approving the opening of many independent public charter schools, CPS turned to the task of right-sizing their portfolio of traditional public schools. As the school year neared an end, the City of Chicago finished a long, public planning process and published the list of almost 50 schools to be permanently shuttered when the summer holiday began. The great idea of school reform—letting market forces force poor schools to close—was in full bloom.

The district said it was ready to implement the change. When the new school year began in just a few months, displaced students would be welcomed into their well-prepared new schools. For a cash-starved school district, this massive dislocation promised long-term savings. For students, the promise was that their new schools would give them a stronger educational experience than the ones they were leaving behind.

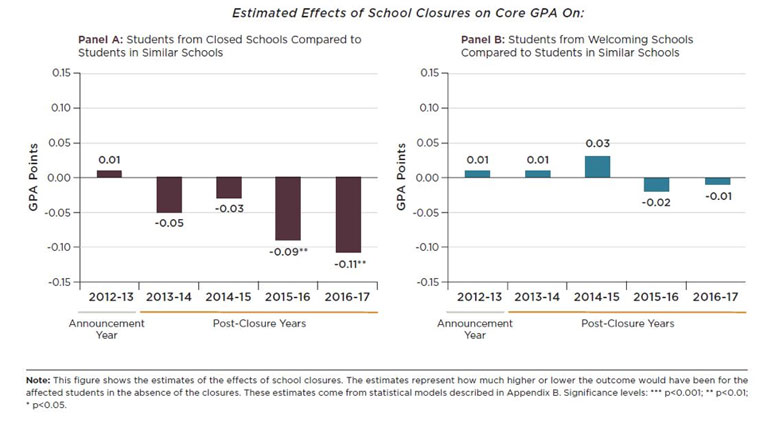

Five years later, the educational outcomes are modest at best, the actual savings hard to see, and the ineffectiveness of the district’s planning and implementation evident. A study published earlier this week by researchers at the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research found that “the reality of school closures was much more complex than policymakers anticipated; academic outcomes were neutral at best, and negative in some instances.”

To make the plan work, the district needed to place 12,000 students who were attending closing schools in new classrooms, prepare the designated receiving schools so that they were ready to accommodate their new students, physically move equipment and supplies to their new locations, reassure parents about the plan, and manage 1,100 staff whose schools were closing.

The physical task of preparing schools for an influx of new students proved daunting. The researchers found that in many cases, the district had not planned effectively.

In addition to having to deal with the clutter of moving boxes and the chaos of unpacking, staff also lamented that some of the welcoming school buildings were unclean, some needed serious repairs, and many upgrades fell short of what was promised or were delayed. Poor building conditions were a barrier to preparedness, undermining community hopefulness about the transition. The inadequacy of the building space resulted in administrators and teachers spending a lot of time unpacking, cleaning, and preparing the physical space, rather than on instructional planning and relationship building.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

A key part of the district’s approach was to provide additional resources to receiving schools so they could strengthen their educational programs. It couldn’t maintain that level of spending over time, however, so many improvements didn’t last: “Many of these initial supports, however, were hard to sustain after the first year, according to school leaders, due to budget cuts in subsequent years and the one-time influx of resources.”

Most critically, CPS underestimated the social dimensions of the sweeping changes they were making. Many of the schools, despite their academic struggles, were important community anchors. Students, families, and staff had strong and important relationships that had been built up over many years. Receiving school personnel were not ready for the feelings of loss and grief that the closures left behind. The researchers found that “staff said they wished that they had more training and support on what it meant to welcome staff and students who just lost their schools. Interviewees wished that their grief and loss had been acknowledged and validated.” And those coming from the closed schools found out that being welcomed was harder than district leaders thought: “Closed school staff and students, in each case, talked about feeling marginalized and not welcomed into the welcoming schools….Staff expressed a need for more training and support in integrating school communities after school closures.”

After five years, the benefits of this pain remain to be seen. According to WBEZ Public Radio, “CPS had said that closing the…schools would save $43 million annually and $437 million over time by not having to fix or maintain the shuttered buildings. But the school district has never provided any detailed information on whether those savings were or will be realized.”

Academically there is little indication that the closings benefited students. “Closing schools—even poorly performing ones—does not improve the outcome of displaced children, on average.…Closing under-enrolled schools may seem like a viable solution to policymakers who seek to address fiscal deficits and declining enrollment, but our findings show that closing schools caused large disruptions without clear benefits for students.”

As student populations decline, school districts face the need to close superfluous facilities. The experience of Chicago points to how difficult this process can be, and the expected benefits require greater effort than locking the door behind the last student. Molly Gordon, the study’s lead author, told WBEZ, “Policymakers make decisions and they hope for a specific outcome or result. But not all the intended benefits play out in reality.” CPS’ current Schools Chief, Janice Jackson, called what happened “unacceptable. We acknowledge that it was imperfect. For me, I can focus on the learnings that came out of that.”

We can certainly hope that this is true. CPS has planned additional school closings for this June. They have a chance to learn from their mistakes and make a new group of displaced students’ experience more positive. We can also hope that educational policy leaders in other districts will take note before they reshuffle their school portfolios. Five years of little benefit is a high price for students, parents, and communities to pay.—Martin Levine