June 16, 2020; Grist and the Washington Post

In an anguished Washington Post op-ed, marine biologist and climate scientist Ayana Elizabeth Johnson quotes Toni Morrison: “The very serious function of racism…is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being.”

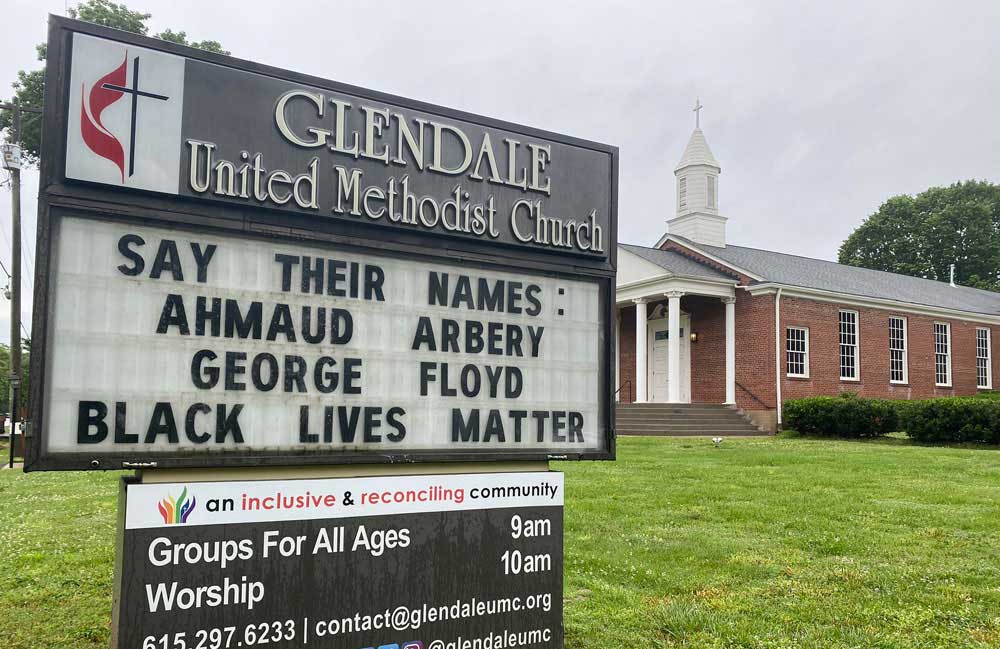

Johnson is driven to “build community around climate solutions.” But the uprising that followed George Floyd’s murder by a Minneapolis police officer has distracted her from that work. As she argues, racism sucks the energy out of Black people and undermines their ability to pay attention to the climate crisis, which already impacts their communities disproportionately.

To move forward and implement the solutions necessary to transform our power grids, our transportation systems, our buildings, and so much more, Johnson says, people of color need to be involved. And to get them involved, white environmental activists need to join the struggle for racial justice. Not just to show solidarity—although that is important—but to eradicate racism so that the US as a whole is equipped to address squarely the threat of planetary extinction.

Johnson supports her argument with data: 57 percent of African Americans report they are concerned about climate change, as do 70 percent of Latinx people, as compared to 49 percent of whites. We cannot afford to have millions of people of color on the sidelines in the fight to save the planet, she tells National Public Radio.

COVID-19 has laid bare the racial fissures in our society, and the deadly impact of policies that relegate people of color to substandard housing in overcrowded neighborhoods littered with toxic industries and waste sites. African Americans are dying of COVID-19 at more than twice the rate of white Americans: 61.6 deaths per 100,000 versus 26.2 deaths per 100,000. The death rate for Latinx persons is also higher than that of whites, at 28.2 deaths per 100,000, even though the nation’s Latinx population is considerably younger than its white population.

The higher rate of infection and death among African Americans and Latinx people has been attributed to a number of factors: overcrowded housing, overrepresentation among “essential workers,” higher use of public transportation, lack of access to regular health care, pre-existing health conditions caused by the stress of racism and poverty, and exposure to air pollution and other toxins.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

A recent Harvard study indicates that even a tiny increase in small particulate air pollution—caused by car exhaust, diesel fumes, and coal-burning power plants—increases the COVID-19 mortality rate. One recent study found that among Californians, Black and Latinx people inhaled “40 percent more particulate matter from cars, trucks and buses” than the state’s white residents, leading to higher rates of asthma and respiratory illness in communities of color. Police brutality and air pollution have millions of people crying, “I can’t breathe.”

There has not been a more stark reminder than COVID-19 of the critical importance of centering racial justice in the fight to create a sustainable future. African American environmental leaders are shining a spotlight on these issues. COVID-19 has prompted the revival of the National Black Environmental Justice Network (NBEJN), which is building an expert network to “help create an equitable green stimulus package, take on the fossil fuel industry, and fight the Trump administration’s seemingly endless orders to weaken environmental protections,” Rachel Ramirez writes in Grist.

“We see these environmental rollbacks as not just fast-tracking project permits, but as a fast-track to the emergency room and cemeteries,” Robert Bullard, co-chair of the network and a professor of urban planning and environmental policy at Texas Southern University in Houston, told Ramirez.

His co-chair, Beverly Wright, notes, “Green stimulus packages often only look at protecting the world, but not protecting people like us.” Wright leads the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice, which has taken on the chemical plants along the Mississippi Gulf Coast. “Any stimulus package dealing with transportation to housing or whatever they’re talking about doing will have to include us and need to be viewed with equity and justice lenses,” she concluded.

In a recent talk with the Boston Globe, Ibram X. Kendi, author of How to Be an Antiracist, notes that policy choices are life-and-death choices. They literally determine who will live and who will die.

To choose life, for people and the planet, we must address both racial injustice and the climate emergency. As Johnson concludes in her Washington Post essay, “To white people who care about maintaining a habitable planet, I need you to become actively anti-racist. I need you to understand that our racial inequality crisis is intertwined with our climate crisis. If we don’t work on both, we will succeed at neither.”—Karen Kahn