October 2017; The Atlantic

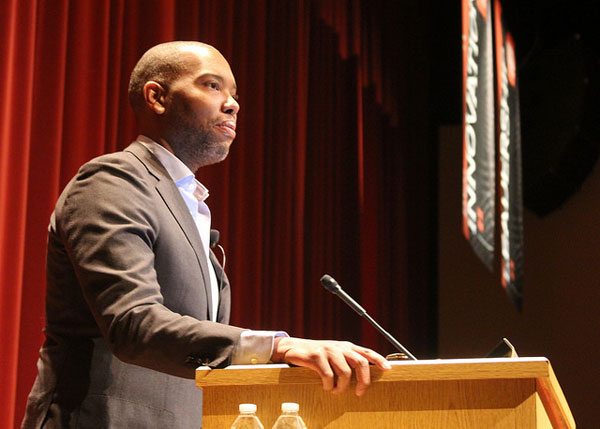

Ta-Nehisi Coates’ essay in the Atlantic, “The First White President,” has gotten a lot of attention. As usual, Coates describes a reality familiar to many people of color but not always so clear for white people, who may not have occasion to connect all the dots.

The main idea in the piece is that “Trump moved racism from the euphemistic and plausibly deniable to the overt and freely claimed,” which “presented the country’s thinking class with a dilemma,” namely their inability to name white supremacy because they themselves are implicated in it. (NPQ wrote about this in the nonprofit sector in last month’s Editors’ Note.)

Coates wrote,

It is often said that Trump has no real ideology, which is not true—his ideology is white supremacy, in all its truculent and sanctimonious power…To Trump, whiteness is neither notional nor symbolic but is the very core of his power…fending off multiple accusations of [sexual] assaults, immersed in multiple lawsuits for allegedly fraudulent business dealings, exhorting his followers to violence, and then strolling into the White House. But that is the point of white supremacy—to ensure that that which all others achieve with maximal effort, white people (particularly white men) achieve with minimal qualification.

But, as Coates points out, this was not enough for Trump. “Trump has made the negation of Obama’s legacy the foundation of his own.” He calls Trump “America’s first white president” because he is “the first president whose entire political existence hinges on the fact of a black president.” Coates deconstructs this as a manifestation of two core features of whiteness—that race is an idea that has to be constructed and maintained by manufacturing and upholding racial difference as central to society, and whiteness is always defined as not being black.

Coates traces the “tightly intertwined stories of the white working class and black Americans” to the prehistory of the U.S., noting that in the early 17th century, when black slaves worked by indentured whites, there was not much racial enmity. But by the 18th century “a bargain emerged: The descendants of indenture would enjoy the full benefits of whiteness, the most definitional benefit being that they would never sink to the level of the slave…But the dignity accorded to white labor was situational, dependent on the scorn heaped upon black labor.”

This has created a national frame in which “the panic of white slavery [the exploitation of white labor by white capitalists] lives on in our politics today,” at the same time that “Black workers suffer because it was and is our lot.” This means that while blacks are much worse off than whites in almost any indicator, it is only white despair that matters. “White slavery is sin. Nigger slavery is natural.”

Coates points out that while many think of identity politics as something that arises in the presence of people of color, it is concomitant with the manufacturing of race. “The model for America’s original identity politics was set” with the frame that “Black lives literally did not matter and could be cast aside altogether as the price of even incremental gains for the white masses.” In short, whites created identity politics.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In History of Sexuality, philosopher Michel Foucault described power as relying on a social differentiation in which that which is affirmed is also simultaneously repressed. Hence, in the U.S., though race is central to the ordering of social, economic, and political forces, it is also not discussed as a core lever for social change. For whites, it is generally more acceptable to talk about class (the result of your interactions in the economic order) than race (a social construction that creates what Kellogg Foundation’s Gail Christopher calls a “hierarchy of human value” and assigns an a priori value to anything you do).

Coates accuses “white pundits and thought leaders” of falling into this trap by “asserting that Trump’s rise was primarily powered by cultural resentment and economic reversal.” But, he notes, the “evidence for this is, at best, mixed.” The strongest predictor of Trump supporters is actually “the racial and ethnic isolation of whites at the zip code level.” In fact, “Trump assembled a broad white coalition that ran the gamut from Joe the Dishwasher to Joe the Plumber to Joe the Banker.”

Coates calls this out as escapism. “In this analysis, Trump’s racism and the racism of his supporters are incidental to his rise.” Coates asserts,

There is a kind of theater at work in which Trump’s presidency is pawned off as a product of the white working class as opposed to a product of an entire whiteness that includes the very authors doing the pawning…Moreover, to accept that whiteness brought us Donald Trump is to accept whiteness as an existential danger to the country and the world.

Escapism allows “no deeper existential reckoning” on the part of whites. We see this same strategy at work in the nonprofit sector, where after six decades addressing the needs of society, we have only recently begun to look at the racialized nature of systemic inequality. Instead, as Coates writes, the core belief “at its most sympathetic,” is that “most Americans—regardless of race—are exploited by an unfettered capitalist economy. The key, then, is to address those broader patterns that afflict the masses of all races.” Coates calls this “raceless antiracism” and implicates the Left in its use, pointing out that “few national liberal politicians have shown any recognition that there is something systemic and particular in the relationship between black people and their country that might requires specific policy solutions.”

Coates sums it up well when he writes that “the scope of Trump’s commitment to whiteness is matched only by the depth of popular disbelief in the power of whiteness.” More specifically, “all politics are identity politics—except the politics of white people.” Given this, Coates writes that “it should not be surprising that a Republican candidate making a direct appeal to racism would drive up the numbers among white voters, given that racism has been a dividing line for the national parties since the civil-rights era.” It’s just that “Trump, more than any other politician, understood…the great power in not being a nigger.”

But, and it is this with which the country is now reckoning, “the power is ultimately suicidal.” While blacks have long been aware of the dangers of whiteness on black bodies, Coates reveals that “the larger threat is to white people themselves, the shared country, and even the whole world.” Trump takes whiteness to its extreme, testing the edges of dictatorship.

Though Coates, in addition to calling Trump “the first white president in American history” also calls him “the most dangerous president,” for him the real danger is those who do not correctly analyze the power at play in the Trump presidency because they are implicated in it. Sadly, as a sector, we haven’t had much to offer in this regard, as we struggle with this ourselves. Hopefully, it’s not too late for us. Coates leaves us with a warning: “It does not take much to imagine another politician, wiser in the ways of Washington and better schooled in the methodology of governance—and now liberated from the pretense of antiracist civility—doing a much more effective job than Trump.”—Cyndi Suarez