The reckoning with racial injustice that the United States and others around the globe have been going through has generated important, powerful changes for individuals and institutions, with more, we hope, on the way. But the path to multiracial democracy and an economically equitable society faces many barriers.

To overcome these barriers requires decentering whiteness. But what does it mean to truly decenter whiteness? And what must the movement built to achieve that look like? These questions animated a report and community dialogue guide that we jointly authored this past June, titled Advancing Well-Being by Transcending the Barriers of Whiteness.

Where to begin? One place to look might be the nation’s response to drug abuse and the stark differences between how white and Black Americans have been treated in this discourse. Notice that when white Americans without a college education started to experience an unprecedented decline in life expectancy, dialogue centered on the economic losses and related pessimism behind the trend. The grim, fatalistic tone was signaled by the titles of such articles and books as Dying of Whiteness: How the Politics of Racial Resentment Is Killing America’s Heartland, Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, and The New York Times’ “Who Killed the Knapp Family?”

An extraordinary amount of attention has been given recently to substance abuse, suicide, and other problems faced by a class of white people whose worsening health and discouraged outlook had fueled right-wing populist politics. This attention was accompanied by greater recognition that substance abuse is primarily a health challenge to be prevented or treated, rather than a crime to be punished, as had been the dominant frame when it was perceived as mainly an issue in Black communities. However, a deeper and broader point is sometimes overlooked: Structural racism not only led to policies and practices that repress Black Americans and deny them freedom, health, and opportunity—it also generated “deaths of despair” among whites and has prevented constructive solutions to pressing problems for the whole country.

That realization reinforces why the nation must leverage the moment to seek to transcend the barriers of whiteness. This will be essential to improving the health and well-being of the 100 million Americans of all races who live in economic insecurity. It will be fundamental to creating an economy that is less extractive and more sustainable. Fortunately, the seeds for this kind of transformative change have been planted, and the efforts to overcome these barriers are well underway.

Whiteness, in the sense that we are using it, does not refer to individual prejudice but rather to the fact that white identity remains the implicit standard of normalcy and entitlement to the rewards of society. This leads to acceptance of the marginalization, “othering,” and, too often, dehumanization of those who are not white. This acceptance is often paired with denial that racism is still an important issue for US society.

Whiteness is also a design challenge. Our laws, regulations, customs, and institutions were designed to advance it and to deny others opportunity. These now need to be redesigned. It’s an enormous task, but also a chance for society to recast norms and institutions in accord with the nation’s core democratic principles. It’s a chance to make sure national norms and institutions meet everyone’s needs—including white people!

The pattern of racialized national politics that we know today, and the divisiveness it fosters, began its modern form in the 1970s and has included several strands of strategy and tactics. There have been several generations of “dog whistle” messages that convey racist sentiments without having to make them explicit or overt. There has been concerted opposition to the scope of the federal government, nominally based in race-neutral libertarian values but in practice growing directly from states’ rights segregationist origins. Racialized appeals to voters reached a new level of messaging sophistication, particularly via social media, by 2016, and fed on not only anti-Black racism and anti-immigrant sentiments directly but also on scorn for “liberal elites.”

Each mainstream institution, profession, and component of government has a legacy and contemporary form of whiteness it needs to confront. The political challenge is to find ways to transform structures, change the rules of the game, and embrace true multiracial democracy.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The failure to have addressed race and racism on a structural level in the past is reflected throughout society. For example:

- The dangerous and inept ways in which police confront and too often kill or wound mentally ill people of all races is a direct consequence of the broader militarization of the culture of law enforcement to control Black and Brown communities.

- The roots of the current housing crisis, affecting entire generations and people of all races, lie in government-sanctioned redlining and other discrimination, which distort home values, undercut the viability of neighborhoods, and diminish financial incentives to build housing for anyone other than the affluent.

- Failure to invest in public education is not only hurting people of color but also hobbling the national economy.

- And, as noted above, the lack of an effective prevention strategy or response to the opioid epidemic now ravaging white working-class communities is a direct consequence of the policies enacted, and alternatives not supported, by the so-called “war on drugs” and resultant mass incarceration of Black and Brown people.

In short, overcoming the barriers of whiteness is essential to addressing almost any social problem one could name, problems which have generated personal pain and perpetuated systemic inequality for a long time.

The extraordinary events of 2020 gave great urgency and new direction to this analysis and to our ideas for how to bring about positive change. The movement confronting anti-Black racism built up great moral force and gained widespread attention and influence. The “racial reckoning” and the support shown by so many white people and mainstream institutions was heartening but merited caution, given the nation’s long history of superficial or short-lived expressions of such solidarity. Indeed, the oppositional messages and backlash to the BLM movement expressed during the 2020 election campaign remind us that white backlash cannot be ignored. The insurrection at the Capitol reinforced the threat to maintaining even conventional representative government at a time that an expanded and reenergized democracy is sorely needed.

The COVID-19 pandemic, with its extreme racial disparities, gave an equally powerful jolt and guidance to our understanding of the relationship between structural racism, health, and well-being. The prevalence of the virus and its correlation with racial inequities in housing, employment, and incarceration reinforced the need to tackle those underlying problems.

Given these immediate and long-term challenges on so many fronts, is transcending the barriers of whiteness even possible? We remain optimistic that it is. We see promise both in the development of new narratives and new policy approaches.

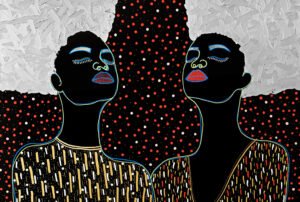

New narrative frameworks and innovative policies, we believe, can generate support that reaches both “persuadable” whites as well as people of color. Our goal should be to not only affirm and equip but also to expand the range of people and organizations committed to racial justice. That expansion calls for a new kind of community dialogue, one that builds upon a common aspiration for well-being that could provide a bridge across racial, class, and cultural divisions.

The new narrative, to be effective, must tap into and resonate with underlying beliefs and perceptions, what Ian Haney Lopez calls “the hidden scaffolding” that undergirds political communications. It should vary to connect with different groups with respect to crafting and delivering messages, but all variants should point in the same direction: generating an understanding of justice that is inclusive rather than divisive and which lays the foundation for powerful collective action to improve health and well-being. Here are four narrative strategies for implementing these changes in governmental, corporate, nonprofit, and philanthropic policies that we invite readers to consider.

- Convey the reasons for economic disruption and dislocation in terms and stories through which white workers can see the common roots of their losses in the experiences of Black ones, as a product of how contemporary capitalism relentlessly sheds jobs and disinvests in places.

- Make the case for how policies initially intended to provide access to the people most excluded by social and economic structures can also benefit many other groups, and indeed the entire nation.

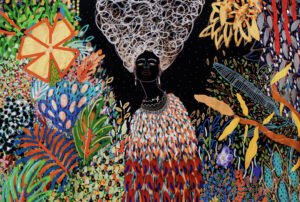

- Present “centering Blackness”—policies and practices that intentionally seek to lift and protect Black people—as an alternative to opinions, attitudes, and beliefs that center whiteness. Centering Blackness is a perspective that will promote collective healing and better outcomes for people of all races.

- Raise public expectations for government to become a force for solving significant economic and social problems.

Already, advocates are hard at work on myriad campaigns to realize these notions in tangible ways. For example, the executive order in support of racial equity by the Biden administration has led PolicyLink and allies to generate a racial equity blueprint for federal agencies. Grassroots efforts for housing justice, health equity, a new vision for public safety, and many other priorities are exhibiting ever-greater alignment. Building the infrastructure and securing the capital for this equity movement will be as critically important as getting its narratives and policy agendas clarified and aligned.

These, then, are the places where advocates need to engage. Recognizing and confronting the barriers of whiteness will make some uncomfortable, and there will always be other worthwhile activities to pursue instead. But movement leaders need to keep, as the saying goes, their eyes on the prize. Addressing underlying issues of economic inequality and structural racism is critical to building a powerful movement for an authentic and just multiracial democracy.