“This administration today, here and now, declares unconditional war on poverty in America.”

This was the call to arms that President Lyndon Baines Johnson announced in his State of the Union address on January 8, 1964. He urged “all Americans to join with [him] in that effort.” LBJ might not have imagined that he launched more than a war on poverty, but the emergence of a civil society dedicated to a peculiar concept, the idea that poor people could not only be helped out of poverty, but that they should have the right and power to speak for themselves and chart their own futures.

Often, the story of the War on Poverty is told in the specific initiatives proposed by LBJ and passed by Congress—Medicare and Medicaid, the Food Stamp program, the Job Corps, VISTA, Head Start, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act to subsidize school districts with large populations of low-income students, the Legal Services Program, and the Community Action Program of anti-poverty agencies. Over time, additional programs were created that became part of the War on Poverty framework—the Community Services Block Grant, the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), weatherization assistance, and more.

Implicit, however, in the implementation of the War on Poverty was an overarching initiative that is palpable throughout today’s nonprofit sector, a dynamic of converting charity, providing assistance to take care of people in need, to community empowerment: urban and rural communities speaking up for themselves, creating and running organizations aimed at helping poor people take control and ownership over their destinies. In a nation in which both political parties have been able to talk only about the “middle class” and have been unwilling to utter anything politically about poverty for fear of consequences from the right—at least until very recently—the War on Poverty sparked a movement of nonprofit organizations and nonprofit leaders active today in pushing for structural change.

“Whatever the cause,” LBJ said that day, “our joint federal-local effort must pursue poverty, pursue it wherever it exists—in city slums and small towns, in sharecropper shacks or in migrant worker camps, on Indian Reservations, among whites as well as Negroes, among the young as well as the aged, in the boom towns and in the depressed areas.”

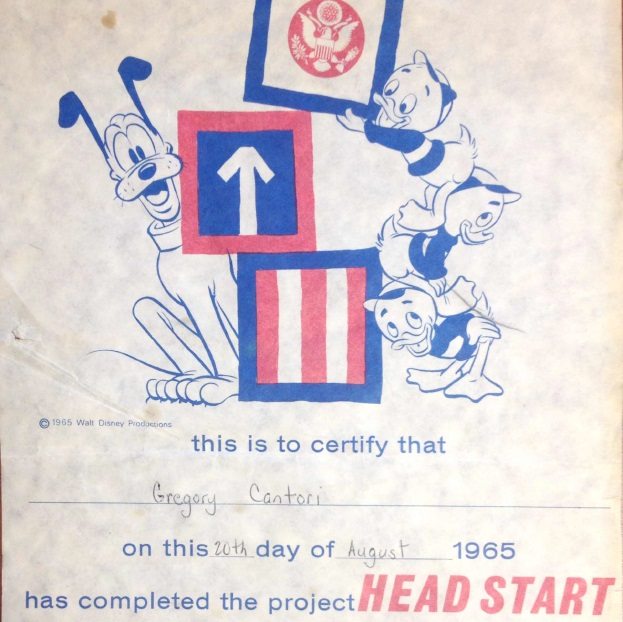

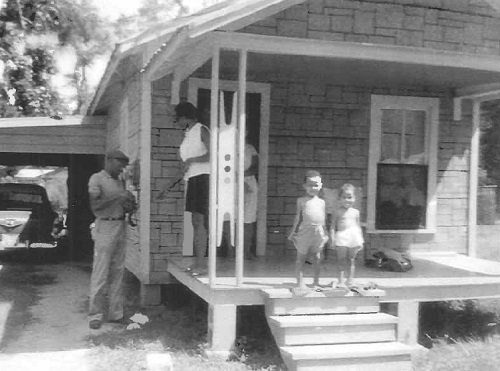

Now head of Maryland Nonprofits, Greg Cantori and his family lived in low-income housing on the South Side of Chicago. In 1965, the five-year-old Cantori was enrolled in the first test run of Head Start, an eight-week summer program that became a school-year program immediately following the pilot effort. One of only a few white kids in the program, Cantori still remembers “the warmth and the sense of excitement of being there.” The current president and CEO of the Ford Foundation, Darren Walker, has a similar feeling, but from having been in the first school-year program of Head Start in 1965 when his family lived in the tiny rural East Texas town of Ames. Living in a shotgun shack, Walker’s mother “wasn’t necessarily thinking about some program,” Walker says. “She just wanted me to start reading.”

Darren and sister Renee in Ames, TX circa ’64

Looking back, Walker sees what Head Start did for him. “It allowed me to imagine a world that wasn’t the world I was in,” he says, “and to aspire and achieve things that weren’t necessarily achieved by people that looked like me and were from places like Ames, Texas.” Cantori still has the certificate he received, signed by Office of Economic Opportunity director Sargent Shriver and by Lady Bird Johnson, for having completed the eight-week program. “When I think about this, of all my certificates and degrees, Cantori says, “this is the one I’m most proud of.” In Walker’s view, “my life has truly come full circle; I’m at the foundation that gave me my head start” and the foundation that actually funded the researchers at Yale back in the day whose experiments with interventions to help poor urban and rural kids with early childhood education became the underpinnings of the Head Start program.

In fact, the Ford Foundation also initiated and funded the Gray Areas Program, originally a six-city pilot effort directed by Ford program officer Paul Ylvisaker that was the precursor for the Community Action Program. Ford also supported the emergence of Community Development Corporations (CDCs), reflected in another War on Poverty initiative called the Special Impact Program. Walker himself joined the leadership of the Abyssinian Development Corporation in Harlem, which received grant support from the Ford Foundation and through the Local Initiatives Support Corporation, a community development intermediary that also emerged from Ford. The War on Poverty reflects the interaction of philanthropic and governmental actors supporting the “joint federal-local effort” that LBJ believed to be so critical to fighting poverty.

“Poverty is a national problem, requiring improved national organization and support,” Johnson said. “But this attack, to be effective, must also be organized at the state and the local level and must be supported and directed by state and local efforts.”

Contrary to the views of ideological critics, the innovations of the original Gray Areas Program agencies in Boston, New Haven, Chicago, and Oakland and the advances of the original Special Impact Program CDCs were not top-down engineering, but locally directed efforts taking advantage of desperately needed national support, in the form of OEO and other program resources, to be fitted to the needs of different localities.

Florence Tandy directs the Northern Kentucky Community Action Commission, exemplifying the imperative of working with communities on the needs and issues they face, hardly a one-size-fits-all template. Her agency has “an odd service area,” Tandy says. “We are in Kentucky, but we are 8 blocks from the Ohio River, where Cincinnati is on the other side…. [Our service area] is really three different cultures; you’ve got an urban culture, you have a suburb an population, and then rural farming, and the families we serve in our rural areas are completely different.” It means, according to Denise Harlow, who started her anti-poverty career 20 years ago as a social worker with the Schenectady Community Action Program, “you serve the entire family… helping the family from a macro perspective.”

“It will not be a short or easy struggle, no single weapon or strategy will suffice, but we shall not rest until that war is won,” Johnson declared. “The richest nation on earth can afford to win it. We cannot afford to lose it.”

What is striking about the cadre of “graduates” of the War on Poverty is that they aren’t giving up. Lil Dupree left a job in community banking to join the community action agency in Kalispell, Montana, now called the Community Action Partnership of Northwest Montana, and after a stint at a national organization in Washington, D.C., she has returned to the local level to a community action agency in southwest Virginia, People Inc. Megan Shreve, currently the director of the Gettysburg-based South Central Community Action Program, left community action for four years to go into the private sector to do software systems work, where she made a lot more money than she ever did in the War on Poverty, but she missed the “amazing, brilliant, exciting” community work of SCCAP and returned.

Now a well-known writer and nonprofit consultant in Oregon, Kathi Jaworski started as a VISTA worker fresh out of school in the North of Howard area in Chicago doing tenant organizing, but years later found herself coming full circle to chair the board of a community action agency in Franklin County, Massachusetts, as it worked through leadership transition issues. Like Jaworski, Stephanie Powers was in VISTA—actually in the first class of “community VISTAs” (hired to work in the communities in which they lived) doing youth organizing in New Hampshire—and later became the Merrimack county director for the Community Action Program Belknap-Merrimack Counties.

The War on Poverty has created a cadre of anti-poverty activists who carry the values and commitments of this movement regardless of where their careers have taken them. Powers, now the director of the Public-Private Partnership Initiative of the Council on Foundations, is a particularly compelling example of this commitment. After her community action agency work, Powers became the director of a Manchester, New Hampshire CETA program. (The Comprehensive Employment Training Act, a federal initiative, was a key program in this nation’s history of workforce development programs.) Many young activists got their starts in community organizations as CETA workers, including Lori Williams, now the associate director of Pace Community Action Agency in Vincennes, Indiana. Williams was a low-income kid with no college as a 20-year-old in 1980 and got her Pace position as a CETA worker just before CETA ceased to be, but she was then hired as a full employee of the agency where she continues to work today.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In Powers’ case, her experience in community action doing community organizing in a town whose economy had been devastated by the closing of a textile mill gave her “a whole different view of the nature of work, what work meant to people…It opened my eyes about the importance of work.” She worked as a jobs counselor with youth and with mothers on welfare. “If people could earn money,” she recalls, “they could make decisions over how they wanted to live their lives and spend their money…[and] not have people tell them how to live.” She describes her community action work as “so absolutely foundational for me, the basic belief structure that I now have that I still truly believe,” reflected in her subsequent career moves such as becoming the national director of a joint Department of Education and Department of Labor “school to work” initiative, then CEO of the National Association of Workforce Boards, followed by her move to the Council on Foundations where she led COF’s National Fund for Workforce Solutions. Like Walker’s career trajectory leading to the Ford Foundation, Powers’ is another story of coming full circle, from organizing among the unemployed of a New Hampshire textile mill town to developing and running national workforce development programs.

“Very often a lack of jobs and money is not the cause of poverty, but the symptom,” the President said. “The cause may lie deeper in our failure to give our fellow citizens a fair chance to develop their own capacities, in a lack of education and training, in a lack of medical care and housing, in a lack of decent communities in which to live and bring up their children.”

When Michael Harrington wrote The Other America, the eye-opening book galvanized the American public—and Presidents Kennedy and Johnson—to commit to eradicating poverty. He was introducing America’s middle class to a large, but to them hidden population of desperately poor people in urban and rural America. Today, anti-poverty activists still find that the overwhelming challenge is the ignorance of too much of the public about the hopes and dreams and commitments of poor people, their willingness and drive to pick themselves up and out of poverty by their bootstraps—so long as they have boots and straps to pull up.

Tandy sees her anti-poverty agency “focusing more on education, on employment, on advocacy…advocating for families, with families, [and] to families to help them imagine a better future for themselves, because low-income families can get discouraged very easy… I’ve tried to be an advocate for those families whose stories we’ve become a part of.” Shreve talks with immense pride about SCCAP’s “Circles Initiative,” which matches low-income families with middle income “allies” to help them “create a future story for themselves and create their own plan” out of poverty.

“You work with the whole family,” Shreve says, and “you see how hard they’re working …[despite] the broken system.” She describes families graduating from the program and becoming “allies” for others. It is a program, she says, that “documents what happens with a family as you work your way out of poverty.”

The stories they tell are not tales of top-down social engineering, but, as Shreve describes, of anti-poverty staff working with low-income families to find solutions. “You see the resiliency of the human spirit, that there’s so much more to people and things than what we understand,” she says. “You see families in difficult circumstances working so hard to develop a good life.” The activists working in the modern-day successors to the original Gray Areas Program agencies are working to empower people to control their lives, not to fit into permanent dependency on an ever-shrinking array of governmental subsidies.

“Our aim is not only to relieve the symptom of poverty, but to cure it and, above all, to prevent it,” Johnson said. “No single piece of legislation, however, is going to suffice.”

Therein lies one of the challenges for the modern day inheritors of the mantle of President Johnson’s War on Poverty. The challenge, Dupree says, is not to deliver services “to keep people in poverty more comfortably, [but to] provide services that are truly helping low-income people to become more self-sufficient.” But, according to Williams, “people tend to focus on the [service-delivery] programs than what we do as a whole.” Too often, the anti-poverty agencies become “siloed” by their programs, as Harlow notes, rather than pulling together a broader, more comprehensive picture of how the agencies adapt and respond to community needs.

Dalitso Sulamoyo, the president and CEO of the Illinois Association of Community Action Agencies, notes that the dependency of some anti-poverty agencies on too much governmental funding “stifles innovation and flexibility.” At IACAA, Sulamoyo lists efforts such as the association’s venture capital arm, which makes small business loans as well as equity investments in businesses from restaurants to RV suppliers with a commitment that the economic returns are funneled back into community action agency core programs. Although focused on two counties in Virginia, Dupree notes that her agency, People Inc., also functions as a CDFI with New Market Tax Credit investments in six states, including an investment in a tire company in South Carolina. At Pace, Williams also reports economic development investments, including the development of a for-profit residential and commercial cleaning business—Pace Ventures Cleaning—that generally employs formerly unemployed or hard-to-employ residents and funnels the profits back into the agency.

Many anti-poverty agencies are and have been delving into economic development, affordable housing ventures, and more. That is due in part to continuing cutbacks in funding, but these new initiatives, entrepreneurial to their core, reflect the need of the War on Poverty for constant reinvention. The public sector funding environment is difficult, with programs that were once reliable income streams for anti-poverty work now threatened by cutbacks, sequestration, and diversion. But the War on Poverty has faced governmental efforts to derail the campaign before. Those with longer histories in the anti-poverty movement recalled President Nixon’s efforts to dismantle the Office of Economic Opportunity only a few short years after President Johnson’s pronouncements, followed some years later by President Reagan’s attempts to undo the support infrastructure for the War on Poverty. As poor people adapt and cope with the challenges they have faced, anti-poverty activists and the agencies they work for have had to do the same.

“Unfortunately, many Americans live on the outskirts of hope—some because of their poverty, and some because of their color, and all too many because of both,” LBJ said. “Our task is to help replace their despair with opportunity.”

But the reality is that after 50 years, this nation still faces the problem of persistent urban and rural poverty plus deepening economic inequalities and disappearing social mobility. “The whole idea of the War on Poverty,” Walker says, “was ultimately social mobility, but we’re learning that social mobility has come to a screeching halt for many people in this country…. We have to recalibrate that conversation.” The nature of poverty is changing, Shreve notes. It includes people who are in the middle class, the working poor, and sometimes working people above the poverty line, unable to pay their bills and in danger of falling into deeper poverty. Tandy adds that “poverty has changed from 1964 to 2014, it’s not the same kind of issues we face then, [and] we have to wage the battle in different ways.” She notes the challenges of predatory businesses, such as payday lenders and rent-to-own businesses, and simply the ever-increasing unaffordable rents of many communities, factors that make “it cost more to be poor now.”

“People who have been doing this work for the last 50 years have faced a lot of naysayers, that we lost the war on poverty, that poverty is not getting any better, but I don’t think this nation has really waged the war that really needed to be raised,” Tandy says. “Once this nation decides it is really important to do, we will really win the war.” “You can throw services at people all day long and it won’t make much of a dent in poverty,” Dupree adds. “You need to change systems.”

But how? Despite having assumed the mantle of leadership at the Ford Foundation where much of the War on Poverty was tested and nurtured, Walker says that “we don’t have time to look back and navel gaze” about the elements of civil society that have their roots in Ford. Rather, he says, “the issues may have changed, poverty may require different interventions, but there are a set of underlying principles that are threads that bind our ability as a society to achieve and provide opportunity, and at the core of that is the public good, the public commons, and public policy.” After 50 years of the War on Poverty, watching today’s pushback on social programs such the Head Start program that educated both him and Walker, Cantori says, “It is history kind of repeating itself.” We may have truly come full circle in the War on Poverty to realize that social and economic conditions change, but the poverty can only be defeated by unending commitments to attack the problems of poverty at their root, to empower low-income people to craft solutions that work best for them and their communities, and to ensure that public policy provides families with the resources to allow them to find their ways to long term self-sufficiency.

On the 50th anniversary of President Johnson’s declaration of the War on Poverty, we should remember his admonition:

“The war against poverty will not be won here in Washington. It must be won in the field, in every private home, in every public office, from the courthouse to the White House.”