June 24, 2018; WNNO New Orleans Public Radio

At NPQ, we have frequently covered the conflict that can arise between tax abatements given to corporations and funding for public schools. For example, in Nashville schools lost $9.3 million to corporate subsidies. In St. Louis, the local paper reports that the loss is nearly $30 million.

In theory, corporate tax abatements are supposed to encourage businesses to invest their resources in new or expanded factories, plants, and offices. This, we are told by tax abatement advocates, will generate more resources for all over time.

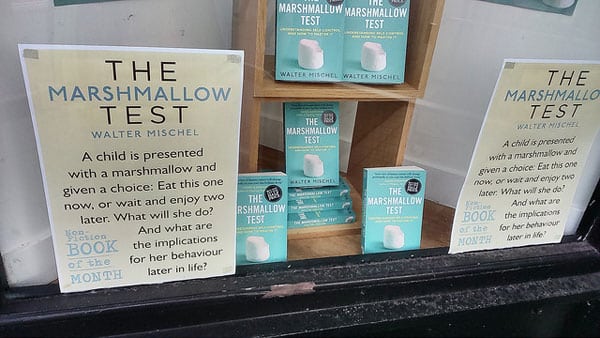

The argument recalls the old marshmallow test where participants are told that refusing one marshmallow for 15 minutes entitles you to two marshmallows 15 minutes later. In theory, the ability of the student to hold out for the 15 minutes was supposed to be a strong indicator of future success, although a more recent study suggests that what the test really shows is that students who come from wealthy families are more secure and thus better able to defer gratification than students from poor families.

Anyhow, do school districts that give up one “marshmallow” now (i.e., current tax dollars) to support tax abatements end up with two marshmallows later?

Turns out that they actually lose the one marshmallow and hurt children in the process. According to a study of Louisiana’s Industrial Tax Exemption Program conducted in 2016 by the nonprofit Together Louisiana, the statewide cost of corporate tax abatements exceeded $16 billion over a ten-year period. Jeanie Donovan, a researcher with the Louisiana Budget Project. told WNNO that for New Orleans, the return on the investment has been miniscule.

“The outcomes for the Industrial Tax Exemption Program have not been great,” Donovan says.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

That’s because rather than seeking exemptions for plant expansions that create jobs, she says companies are getting exemptions for expanding automation and reducing the reliance on human workers. In the last 20 years, the tax breaks have cost the city $178 million dollars, and they’ve created 233 jobs. Do the math, and that comes out to a cost of around $765,000 per job created.

Since 2016, the Orleans Parish School Board has been given the right to reject tax abatements granted by the state. A new request from Folgers Coffee for a new set of abatements in support of 11 new jobs is coming to their agenda soon. The cost to the school district in tax revenues foregone is $3 million.

Nicole Saulny, principal of Esperanza Charter School, has a vision of the improvements her school would need to meet her students’ educational requirements. She told New Orleans’ public radio station, “I would build the gymnasium; I would put Smartboards in each classroom; each classroom would have their own computer carts with laptops.” She’d hire more teaching assistants and give raises to staff, too.

Saulny’s vision can only be realized if the financial resources are available. Certainly, having $3 million more would help realize this vision for her students.

This local school board may soon debate the value of 11 jobs versus spending $3 million more on their students next year. It is a debate that should be happening more widely in state capitals and city halls across the country. If the expensive bidding war that continues to bedevil Amazon’s HQ2 is an example, policy leaders have yet to learn their lessons. NPQ, which has been following this issue, highlighted an open letter from a group of economists and nonprofit leaders asking for caution:

Tax giveaways and business location incentives offered by local governments are often wasteful and counterproductive, according to a broad body of research. Such incentives do not alter business location decisions as much as is often claimed and are less important than more fundamental location factors. Worse, they divert funds that could be put to better use underwriting public services such as schools, housing programs, job training, and transportation, which are more effective ways to spur economic development.

Alas, all too often, the allure of the future gold at the end of the rainbow painted by those dangling new investments in return for huge tax benefits and other public funds seems too great to incent politicians to look behind the curtain.—Martin Levine