This article comes from the winter 2020 edition of the Nonprofit Quarterly as part of an article series on “America’s healthcare crisis.” To learn more about this topic, please join us on Thursday, January 21st, at 2 pm EST for a free webinar on Health, Racial Disparities, and Economic Justice.

As COVID-19 hospitalizations spiraled out of control last spring, thousands of people stood at windows and on front porches or balconies each evening, clapping for doctors and nurses and emergency workers who were risking their lives to care for the sick and dying. That praise was well deserved, but it left out millions of nursing aides, housekeepers, medical assistants, food service workers, and many more healthcare workers largely invisible to the general public. Ten months into the crisis, as COVID-19 surges across the country, millions of low-wage workers who have been crucial to our COVID response are demanding to be prioritized, so that they can stay safe (and sane) and protect their families from a sometimes-fatal disease.

The Healthcare “Underclass”

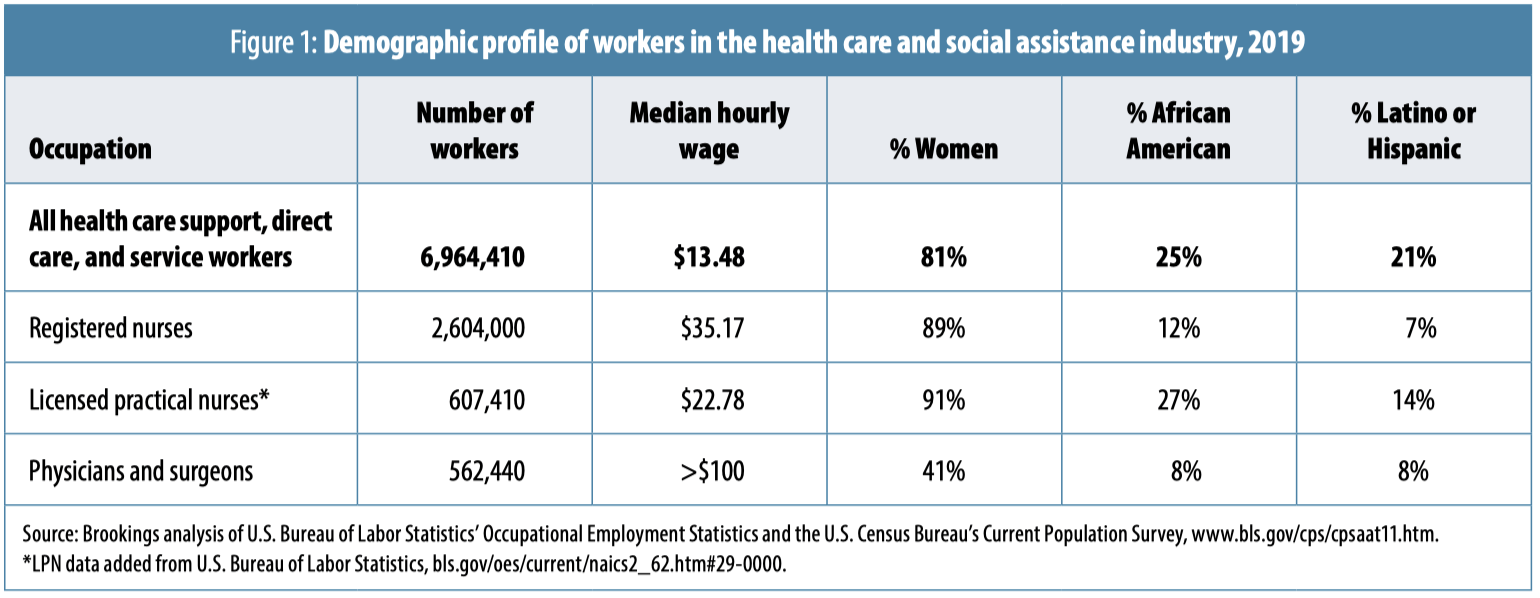

Over 18.5 million people work in healthcare in the United States.1 Of these, only about 600,000 are doctors. By contrast, nurses account for nearly four million healthcare workers. These nurses are spread along a hierarchy based on education, licensing requirements, and workplace settings. Advanced practice nurses are more akin to primary care doctors, and relatively small in number. Registered nurses (RNs) number about three million, with about two-thirds working in hospital settings. A third category of nurses, licensed practical nurses (LPNs)—sometimes called licensed vocational nurses (LVNs)—number about 607,000, with nearly half working in long-term-care settings.2

Doctors, with their years of education, receive the most respect and privileges of all healthcare providers, earning in excess of $100 per hour.3 RNs, who manage much of the day-to-day care on hospital floors and in long-term-care settings, earn a median wage of $35 per hour.4 LPNs work under the direction of RNs in acute care and long-term-care settings, administering medications, tracking patient status, and keeping patients comfortable; they have considerably less prestige, and earn a median wage of $22.83 per hour.5 Since COVID-19 arrived, nurses up and down the hierarchy have carried much of the burden. Long concerned about understaffing, they find themselves left struggling to care for far too many patients with critical needs as the virus surges.

Nurses, however, are not the only health workers on the front lines. Another seven million workers occupy “low-wage” roles that also involve direct contact with patients. The Brookings Institution parses these workers into three types of occupations:6

- Healthcare support workers: Those who assist providers such as doctors and nurses—for example, orderlies, medical assistants, phlebotomists, and pharmacy aides.

- Direct care workers: Home health workers, nursing assistants, and personal care aides who support people with physical, cognitive, and social needs in nursing homes, congregate facilities, and private homes.

- Healthcare service workers: Housekeepers, janitors, and kitchen and dining workers in hospitals, nursing homes, and other residential care settings.

These workers earn a median wage of $13.48 per hour. Among the lowest paid are home health and personal care workers, who earn a median hourly wage of $11.57.7

Well-paid clinicians tend to be white and male, while nursing and low-wage healthcare jobs are filled by women, with people of color overrepresented among the lowest-paid occupations (see Figure 1). Across low-wage healthcare support, direct care, and healthcare service occupations, 81 percent of workers are female, 25 percent African American, and 21 percent Latinx.8 LPNs, next on the hierarchy, are also mostly female (91 percent), and here, too, women of color are overrepresented: 27 percent of LPNs are African American, and 14 percent are Latinx.9 RNs, too, are 89 percent female, but this higher-wage occupation is dominated by white women. Of RNs, 12 percent are African American, and 7 percent are Latinx. Women of color represent the majority of the lowest-paid healthcare workers: long-term-care nursing assistants and home care workers.10

Low-wage healthcare workers, including LPNs, face an array of challenges, from general lack of respect to inconsistent hours and shifts to less access to paid leave and employer-sponsored health coverage. These are critical protections that workers need to stay home and get well if they become infected. Despite the large numbers of healthcare workers without robust benefits (e.g., 16 percent of home care aides have no health insurance, twice the rate of the general population, and 52 percent work part time11), healthcare employers were exempted from the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, the relief bill passed in April that extended emergency paid leave to workers who became ill with COVID. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, almost all healthcare workers (17.7 million) were excluded. Though the data were not broken down by occupation, the Kaiser analysis points out that among the excluded workers, 75 percent were women, 39 percent people of color, 24 percent work part time, and 18 percent were low-wage employees. While doctors and RNs are likely to have health insurance and sufficient paid leave to remain out of work for two weeks or more, that is not the case for part-time and low-wage workers.12

Undervalued Workers Put at Higher Risk from COVID-19

Healthcare workers with direct patient contact, including nurses (both RNs and LPNs) and low-wage direct care workers, are most at risk for COVID-19. The latest research suggests that the risk is highest for those who work in inpatient hospital settings and residential and long-term-care settings, particularly those without access to adequate personal protective equipment (PPE).13 As difficult as it has been for hospitals to maintain sufficient supplies of PPE, workers in nursing facilities and in home care have never been prioritized, despite their vulnerability to COVID-19. About half of LPNs work in long-term-care settings, alongside nearly 3.5 million nursing aides, home health aides, and personal care aides, the lowest paid and least respected among our healthcare workers.14

Underreporting of data has made it difficult to assess the level of infection and death among healthcare workers. The CDC reports, as of December 17, 2020, 3:05 p.m., 278,370 COVID-19 cases and 928 deaths among healthcare workers, including doctors, nurses, and those in multiple other roles in healthcare settings.15 Of those who have become ill, more than half (53 percent) have been workers of color (26 percent Black, 12 percent Latinx, and 9 percent “Asian”). Workers of color were also more likely to be hospitalized: 52 percent of hospitalized healthcare workers have been Black and 9 percent have been Latinx.16

Kaiser Health News and the Guardian have identified over 1,400 deaths among healthcare workers, and they also found that the majority of healthcare workers dying from COVID-19 are Black, Latinx, and “Asian American.”17 As of September 2020, National Nurses United identified 1,718 deaths among healthcare workers, 213 of them registered nurses. Of these, more than half were nurses of color, despite representing only 24 percent of all registered nurses. Among those who have died, 32 percent were Filipino and 18 percent were Black.18 Filipino nurses make up about 4 percent of the U.S. nursing workforce, and, at least early in the pandemic, they were more likely to be in intensive care units (ICUs) and doing risky procedures without sufficient PPE.19

Most striking is a recent analysis of deaths among nursing home workers, data analyzed by Harold Pollack, a professor at the School of Social Service Administration at the University of Chicago. Among the 91,000 deaths in nursing homes, Pollack has identified at least 1,000 among workers—a number, he says, that is likely an undercount.20 To put that in perspective, the CDC reports 928 deaths among all healthcare workers (as noted earlier), while Pollack has identified at least 1,000 long-term-care workers—many of whom earned less than $15 per hour—as having lost their lives due to the pandemic.

Healthcare Workers Still Short on PPE

Though the data are not robust, it is clear that PPE shortages are one of the key factors that put healthcare workers at risk—and as cases surge again, the supply problem continues to be unresolved. 3M, the largest domestic producer of N95 masks in the United States, told CBS MoneyWatch in early November, “U.S. and global demand for PPE continues to far exceed supply for the entire industry.”21

In a September survey of twenty-one thousand registered nurses nationwide, the American Nurses Association found that 42 percent of respondents were coping with PPE shortages they characterized as “widespread or intermittent.”22

While registered nurses are asked to reuse N95 masks for one or more shifts,23 LPNs and others further down the hierarchy—who clean rooms or serve food to patients or care for elders in long-term-care settings—have even less access to equipment they need to stay safe. In a series of interviews by Molly Kinder of the Brookings Institution, health support and service workers noted how often they were overlooked in the distribution of PPE.24

“We had one patient that we thought had the virus,” said Andrea, a hospital housekeeper. “We asked the charge nurse to send us to get fit-tested for the N95 mask that everyone was wearing. Her response was, ‘No, these are for special people.’ And we were just like, ‘We are here to clean the room and make sure no one else gets the virus, and you are telling us that these are for special people?’”25

Nursing home workers have faced some of the greatest challenges. Nearly 40 percent of COVID-19 deaths have been among nursing home residents; yet PPE shortages have never been resolved, putting both residents and poorly paid LPNs and direct care staff at risk. A study by the U.S. Public Interest Research Group (PIRG) found that in late August, 2,981 nursing homes nationwide “had dangerously low supplies of one or more types of PPE.” That’s about 20 percent of nursing homes nationwide reporting that they didn’t have a one-week supply of at least one type of PPE—N95 masks, gowns, eye protection, or hand sanitizer—at the end of the summer.26

Vulnerable nursing assistants are already on edge, coping with post-traumatic stress from the first wave of COVID infections. Edwina Gobewoe, a certified nursing assistant at a skilled nursing facility in Rhode Island, told Judith Graham of Kaiser Health News, “It’s been overwhelming for me personally.”27 Not only was there the trauma of losing patients, but colleagues as well. As Graham writes:

At least 15 residents died of COVID-19 at Charlesgate [where Gobewoe works] from April to June, many of them suddenly. “One day, we hear our resident has breathing problems, needs oxygen, and then a few days later they pass,” she said. “Families couldn’t come in. We were the only people with them, holding their hands. It made me very, very sad.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Every morning, Gobewoe would pray with a close friend at work. “We asked the Lord to give us strength so we could take care of these people who needed us so much.” When that colleague was struck by COVID-19 in the spring, Gobewoe prayed for her recovery and was glad when she returned to work several weeks later.

But sorrow followed in early September: Gobewoe’s friend collapsed and died at home while complaining of unusual chest pain. Gobewoe was told that her death was caused by blood clots, which can be a dangerous complication of COVID-19.28

Nurses and Nursing Assistants Demand Greater Safety and Respect

For exhausted and traumatized healthcare workers, the situation on the ground is continuing to worsen. The only winners appear to be staffing-agency nurses, particularly those who are willing to travel. Temporary critical care nurses are earning $5,000 to $6,000 per week,29 while unionized staff nurses (about 20 percent of the workforce) are striking to bring attention to deteriorating working conditions and the failure of multiple hospital systems to negotiate contracts.

In Bucks County, Pennsylvania, eight hundred nurses went on strike the last week in November, citing dangerously low staffing levels. Represented by the Pennsylvania Association of Staff Nurses and Allied Professionals, nurses at St. Mary Medical Center, which is owned by the Catholic health system Trinity Health Mid-Atlantic, have been attempting to negotiate their first contract for more than a year.30 They tried to get the hospital to come to the table during the summer months, when the number of COVID-19 patients had subsided, but the hospital did not make an offer.31 Now the nurses are walking out at a moment when they may have more leverage.32

Headquartered in Livonia, Michigan, Trinity Health owns over ninety hospitals across twenty-two states, five in the Philadelphia area. Nurses at St. Mary Medical Center have been unimpressed with Trinity’s management. Robert Bozek, a St. Mary critical care nurse for twelve years, says Trinity management decisions have been slowly undermining the hospital’s quality of care. “Trinity is not bought into Bucks County,” he told the Philadelphia Inquirer. “They’re bought into Livonia. We need someone to keep them in check.”33

With an increasing number of hospitals owned by large state or national systems, or, in the case of for-profit hospitals, private equity,34 Bozek points to a growing problem: executives, who are not rooted in the community, care more about squeezing out profits than those tasked with delivering care. For Trinity, St. Mary was a major profit center prior to the pandemic, earning $58 million annually for the last three years and supporting outsized multimillion-dollar executive salaries.35

Years of cost cutting had already strained relationships between healthcare organizations and hospital staff before the pandemic, write Dr. Wendy Dean and Dr. Simon G. Talbot, cofounders of Moral Injury of Healthcare, an organization concerned with systems that compromise providers’ moral compass.36 In response to changes in reimbursements and corporate ownership, the authors argue, hospital executives squeezed all the slack out of the system, increasing pressure on providers while also making it difficult to respond to even minor surges, much less a pandemic. Now, they note, the systems are facing two simultaneous cataclysms:

The abject failure of preparedness driven by the dogma that market forces can best shape health care, and the catastrophic failure at the highest levels of leadership in the U.S. to adequately address and control the pandemic. Health care workers are left to manage in the ensuing chaos feeling disposable, devalued, and demoralized.37

“Nurses are totally burned out,” says Deborah Burger, a registered nurse and copresident of National Nurses United, the nation’s largest union of RNs. “We’ve normalized this crisis. We’re staffing [hospitals] as if [these] were normal times and [they’re] not. Nurses who used to have, say, one [patient] code per shift are now seeing that exploding to where there are multiple codes going on. And it takes a toll.”38

As the crisis explodes, nursing shortages are growing all over the country. Olivia Goldhill, reporting in STAT, notes that in one Texas hospital, 30 percent of the staff are out due to COVID-19, either isolating because of exposure, being sick, or caring for someone who is sick. The Mayo Clinic reported one thousand staff out with COVID-19 earlier in the fall.39 The nurses left on the floor are under even more stress, working twelve-hour and sometimes longer shifts.

Kencee Graves, associate chief medical officer at University of Utah Health, said, “Our numbers keep increasing…. Our nurses feel like there’s no end in sight. They get here, work 12-hour shifts in PPE, it’s just this churn of seeing critically ill patients. And then you go to your community and see peak numbers, and having people continue to go to bars and restaurants.”40

That’s a setup for the type of moral injury that Drs. Dean and Talbot are talking about. It is driving a wave of strikes in multiple states41 and decisions to leave nursing altogether.42 Though data on how many nurses have left the profession are scarce, hospital decisions to ration PPE, to extend shifts, and to ask nurses who have tested positive to return to work if asymptomatic, as happened recently in North Dakota,43 have made nurses feel they are being sacrificed rather than supported. Rebecca, a nurse interviewed by NBC, explained: “We didn’t sign up to be sacrificial lambs. We didn’t sign up to fight a deadly disease without adequate resources,” she said. “We’re told we’re soldiers. Well, you don’t send soldiers to war without a gun and expect them to do their job, but you are doing that to us.”44

The challenges faced by hospital-based RNs are multiplied for those further down the hierarchy: LPNs and low-wage nursing home and home care workers. In June, Service Employees International Union (SEIU), which has organized about seventy-five thousand nursing home workers (about 10 percent), launched a nationwide campaign to protect workers and residents in long-term-care facilities.45 The union released survey results that showed nearly 80 percent of nursing home workers felt that doing their jobs put their lives at risk. Half the workers surveyed also said that nursing homes were putting residents at risk.46 Most of these workers, earning on average less than $25,000 per year, cannot afford to give up their jobs.47

SEIU presented a list of demands in June that nursing home workers in Chicago recently put to the test. Striking workers demanded a $15 minimum wage, double-time hazard pay, better COVID-19 testing protocols, and sufficient, medically certified PPE. After eleven days, Infinity Healthcare reached a tentative agreement with the union, which includes a $15.50 starting wage for certified nursing assistants and at least $1 per hour raise for workers such as cooks and housekeepers, hazard pay in facilities with COVID-19 cases, and five additional sick days for COVID-19-related illness.48 The union is also pressing to organize more workers to ensure they have a seat at the table in deciding their fate.49

In addition to demanding paid sick days and sufficient staffing to protect residents and workers, SEIU wants an “end [to] legal protections for nursing home corporations and employers who have failed to protect all nursing home workers and residents.”50 Rather than hold nursing homes accountable for their failures, at least eighteen states have passed measures to ensure corporate owners cannot be sued.51 In addition, the federal government doled out nearly $5 billion to nursing homes to help pay for testing, PPE, and better infection control,52 but without accountability, it’s not clear how that money has been used. It certainly hasn’t gone to boost pay and protections for frontline workers.

Though critics have pummeled unionized workers for walking off their jobs during a health crisis, evidence demonstrates that unionized nursing homes have outperformed nonunionized homes during the pandemic. A study in New York State found that nursing homes with unions were associated with a 42 percent relative decrease in COVID-19 infection rate among residents and a 30 percent decrease in mortality. The researchers attributed the better outcomes to the effort by unions to ensure their members got access to PPE. Unions were associated with a 13.8 percent relative increase in access to N95 masks and a 7.3 percent relative increase in access to eye shields.53 Better pay and benefits will also have made a difference, decreasing the need for workers to have multiple jobs or return to work when ill.

A Workforce Agenda for the Future

As the new administration takes office in January, it will be confronting the worst health crisis in a century, along with a devastated economy. There are, however, some immediate steps that can be taken to increase safety for our most vulnerable healthcare workers while also reducing the spread of COVID-19.54 These include the following:

- Keep workers safe: Use the Defense Production Act to direct the production of masks and other PPE and ensure that every hospital, long-term-care facility, and home care agency has a sufficient supply. Also, ensure regular testing of all healthcare workers and that all healthcare workers are prioritized for the first vaccines.

- Increase wages for frontline health workers: Bring the federal minimum wage to $15, and require hazard pay, as well. Any additional funding for nursing homes and home care agencies should be directed to increasing wages for the lowest-paid workers, improving testing, and increasing PPE supplies.

- Expand paid leave: Make sure that essential healthcare workers are included in any extension of paid leave benefits in the upcoming new relief bill.

- Remove barriers to forming unions: Unions represent only a small minority of nurses, nursing aides, and other frontline care, support, and service workers. Unions have proved that by keeping their members safe, they also improve outcomes for the patients. The Biden administration needs to make it easier for unions to organize, and prevent corporate leaders from interfering with that process.

…

COVID-19 is revealing the deep cracks in the U.S. healthcare system, particularly for those who labor day in and day out to save lives and give comfort. The deregulated, decentralized market-driven system, when combined with a government that simply doesn’t care, has left workers vulnerable to illness and death themselves. Whether healthcare workers become sick at work or because COVID-19 has spread so widely in their communities, we now face a crisis within a crisis, as health and long-term-care providers reckon with insufficient staffing that will put further pressure on those who remain.

As with so many challenges facing the United States today, this could be a transformational moment in which we reassess the value of our essential workers and invest in a caring future. Or, we could return to a system in which health systems gobble up more and more resources while giving back as little as possible to their employees and communities. The choice is ours.

Notes

- Samantha Artiga et al., COVID-19 Risks and Impacts Among Health Care Workers by Race/Ethnicity (San Francisco: Kaiser Family Foundation, November 11, 2020).

- “May 2019 National Industry-Specific Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates: Sector 62—Health Care and Social Assistance,” Occupational Employment Statistics, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; “Occupational Employment and Wages, May 2019: 29-2061 Licensed Practical and Licensed Vocational Nurses”; and “Occupational Employment and Wages, May 2019: 29-1141 Registered Nurses.”

- Physicians and Surgeons: Pay, Occupational Outlook Handbook, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, last modified September 21, 2020; and see Jacquelyn Smith, “Here’s how much surgeons, lawyers and 18 other top-earning professionals make per hour,” Business Insider, November 29, 2016.

- “Occupational Employment and Wages, May 2019: 29-1141 Registered Nurses.”

- “Occupational Employment and Wages, May 2019: 29-2061 Licensed Practical and Licensed Vocational Nurses.”

- Molly Kinder, “Essential but undervalued: Millions of health care workers aren’t getting the pay or respect they deserve in the COVID-19 pandemic,” Brookings Metro’s COVID-19 Analysis, Brookings, May 28, 2020.

- Ibid.; and for a more detailed analysis of the direct care workforce, see Direct Care Workers in the United States: Key Facts (New York: PHI, 2020).

- Kinder, “Essential but undervalued.”

- “May 2019 National Industry-Specific Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates: Sector 62—Health Care and Social Assistance.”

- Kinder, “Essential but undervalued.”

- Direct Care Workers in the United States: Key Facts.

- Michelle Long and Matthew Rae, “Gaps in the Emergency Paid Sick Leave Law for Health Care Workers,” Kaiser Family Foundation, June 17, 2020.

- Long H. Nguyen et al., “Risk of COVID-19 among front-line health-care workers and the general community: a prospective cohort study,” The Lancet 5, no. 9 (September 2020): E475–83.

- “Occupational Employment and Wages, May 2019: 29-2061 Licensed Practical and Licensed Vocational Nurses.” For home care aides, nursing assistants, and residential care aides, see Direct Care Workers in the United States: Key Facts.

- “Cases & Deaths among Healthcare Personnel,” CDC COVID Data Tracker, December 17, 2020, 3:05 p.m.

- Artiga et al., “COVID-19 Risks and Impacts Among Health Care Workers by Race/Ethnicity.”

- “Lost on the Frontline,” The Guardian and Kaiser Health News, accessed December 6, 2020.

- Sins of Omission: How Government Failures to Track Covid-19 Data Have Led to More Than 1,700 Health Care Worker Deaths and Jeopardize Public Health (Silver Spring, MD: National Nurses United, September 2020), 5.

- Usha Lee McFarling, “Nursing ranks are filled with Filipino Americans. The pandemic is taking an outsized toll on them,” STAT, April 28, 2020.

- Judith Graham, “Long-Term Care Workers, Grieving and Under Siege, Brace for COVID’s Next Round,” Kaiser Health News, Kaiser Family Foundation, November 16, 2020.

- Megan Cerullo, “Supplies of N95 masks running low as COVID-19 surges,” MoneyWatch, CBS News, November 6, 2020.

- “New Survey Findings from 21K US Nurses: PPE Shortages Persist, Re-Use Practices on the Rise Amid COVID-19 Pandemic,” press release, American Nurses Association, September 1, 2020.

- See, for instance, Brittany Lyte, “Nurses at Kapiolani Medical Center Demand Better Coronavirus Protections,” Honolulu Civil Beat, December 2, 2020.

- Molly Kinder, “Meet the COVID-19 frontline heroes,” Brookings, May 2020.

- Ibid.

- Teresa Murray and Jamie Friedman, Nursing Home Safety During COVID: PPE Shortages (Denver, CO: U.S. PIRG; and Santa Barbara, CA: Frontier Group, October 2020), 1.

- Graham, “Long-Term Care Workers, Grieving and Under Siege, Brace for COVID’s Next Round.”

- Ibid.

- Olivia Goldhill, “‘People are going to die’: Hospitals in half the states are facing a massive staffing shortage as Covid-19 surges,” STAT, November 19, 2020.

- Juliana Feliciano Reyes, “As coronavirus cases rise, 800 Bucks County nurses go on strike over ‘dangerous’ staffing levels,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 17, 2020.

- 6 abc Digital Staff, “Nearly 800 nurses strike at St. Mary Medical Center in Bucks County,” 6abc Action News, November 18, 2020.

- Reyes, “As coronavirus cases rise, 800 Bucks County nurses go on strike over ‘dangerous’ staffing levels.”

- Ibid.

- Michael Furukawa et al., “Consolidation And Health Systems In 2018: New Data From The AHRQ Compendium,” HealthAffairs (blog), November 25, 2019.

- Reyes, “As coronavirus cases rise, 800 Bucks County nurses go on strike over ‘dangerous’ staffing levels.”

- Wendy Dean and Simon G. Talbot, “Beyond burnout: For health care workers, this surge of COVID-19 is bringing burnover,” STAT, November 25, 2020.

- Ibid.

- Danielle Renwick, “‘Many of us have PTSD’: Pennsylvania nurses strike amid Covid fears,” The Guardian, November 21, 2020.

- Goldhill, “‘People are going to die.’”

- Ibid.

- November and early December 2020 saw strikes in Washington State, Hawaii, New York, Illinois, and Pennsylvania. Ian Kullgren, “Health-Care Workers Turning to Strikes as Covid-19 Surges Again,” Bloomberg Law, November 24, 2020; Renwick, “‘Many of us have PTSD’”; and Lyte, “Nurses at Kapiolani Medical Center Demand Better Coronavirus Protections.”

- Safia Samee Ali, “Why some nurses have quit during the coronavirus pandemic,” NBC News, May 10, 2020.

- Danielle Renwick, “Anger After North Dakota Governor Asks COVID-Positive Health Staff to Stay on Job,” Kaiser Health News, Kaiser Family Foundation, November 18, 2020.

- Ali, “Why some nurses have quit during the coronavirus pandemic.”

- “Amid COVID-19 Devastation, Nursing Home Workers Launch Nationwide Campaign to Protect Workers, Residents,” SEIU, press release, June 18, 2020.

- “National Survey Shows Government, Employers Are Failing to Protect Nursing Home Workers and Residents,” SEIU, press release, June 9, 2020.

- Direct Care Workers in the United States: Key Facts, 1.

- Manny Ramos, “Nursing home workers reach tentative deal to end strike against Infinity,” Chicago Sun-Times, December 4, 2020; and Scott Vogel, “Infinity Workers: Check Out Our New Tentative Agreement!,” SEIU HCII, December 5, 2020.

- “Amid COVID-19 Devastation, Nursing Home Workers Launch Nationwide Campaign to Protect Workers, Residents.”

- Ibid.

- Abigail Abrams, “‘A License for Neglect.’ Nursing Homes Are Seeking—and Winning—Immunity Amid the Coronavirus Pandemic,” Time, May 14, 2020.

- “HHS Announces Nearly $4.9 billion Distribution to Nursing Facilities Impacted by COVID-19,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, press release, May 22, 2020.

- “In New York State Unionized Nursing Homes, Lower COVID-19 Mortality,” HealthAffairs (blog), September 10, 2020.

- These recommendations are taken from several sources, including Kinder, “Essential but undervalued,” and Murray and Friedman, Nursing Home Safety During COVID.