August 7, 2017; Washington Post

The article “Rural Appalachia lags the rest of the country in infant mortality and life expectancy” provides an overview of a new study showing a dramatic decline in key health indicators in the Appalachian region. Appalachia is an area of rugged land stretching from Maine to Mississippi, just a few hours’ drive from the thriving coastal cities of the U.S. According to the article,

The country made gains on those health measures over the next two decades, but progress in Appalachia stalled. Between 2009 and 2013, the infant-mortality rate was 16 percent higher in Appalachia than in the rest of the country. People could expect to live 2.4 years less than their counterparts in the rest of the United States.

In contrast to many media sources, which adapted the AP story to emphasize a stereotype of reckless hillbillies with bad health behaviors, Carolyn Y. Johnson’s article looked at other factors that could account for the sudden drop in these health indicators. After all, these rural dwellers didn’t just begin to have problems with alcohol, tobacco, and obesity in 2009. Lack of access to healthcare facilities and the emergence of the opioid epidemic can account for some of the divergence, but neither is significant enough to account for the disparity, according to Ms. Johnson’s account.

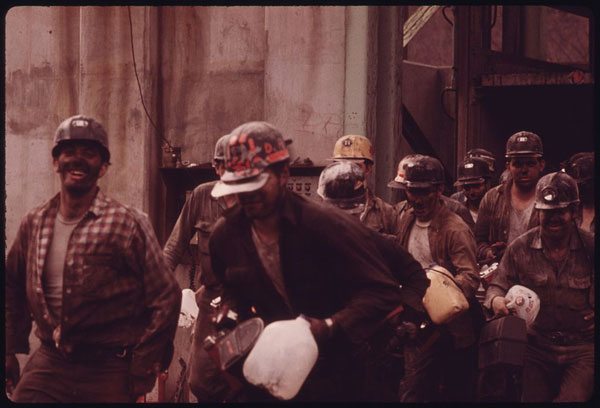

What’s not examined in the article are the impacts of the degradation of air, land, and water; poor housing conditions that foster chronic illnesses; and a prevalence of high-risk occupations like agriculture, mining, and logging. But, again, none of these factors have changed dramatically during the study period. Ms. Johnson does note that one important explanation for the disparity could be the outmigration of healthy individuals, but fails to link depopulation to a cultural malaise of the “left behind.”

Another survey out this past week comes from academic superstar Raj Chetty. Daily Yonder reports on the study in “The Rural Advantage: Rural Upbringing Raises Kids’ Future Earnings, Study Shows.” Rural communities vary widely in how much they promote or retard pathways to adult success, and the article describes some key elements: “Communities that are less racially segregated, that don’t have wide disparities in income, that have good schools and have a strong civic life produce grown-ups who earn more than people who grow up in places without those qualities.”

From that short description of a good community, one might guess that Appalachia’s counties would stand out as examples of “non-metro areas with negative impact” on the Daily Yonder map. But that’s not the case; instead, Appalachia is a hodgepodge of counties with positive and negative impact.

Dr. Chetty’s study hints that perhaps outmigration of young people links these two studies. “Children from many of these counties may not earn their higher salaries at home…[M]ost will move off to the big cities. But once there, they will earn more.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

A strength of Chetty’s study that’s missing in the study of health disparities is the use of very local data to distinguish among rural counties. The health disparities study, by looking at all U.S. data vs. data for the portions of the 13 states that make up Appalachia, may well be missing important local differences. Then, too, each study is a snapshot of a period of time during which massive changes in economics (the Great Recession) and healthcare (the advent of the ACA) were shaping the landscape in every community. Maybe, depending on social resilience, communities responded to these challenges differently.

Appalachia and rural America have been exporting young people to “the big city” for a century, beginning around the World War I when national service, urban industrialization, and rail and highway transportation paved the path to individual prosperity outside the region. At the same time as the pull of the city took the best and the brightest, the traditional rural occupations of mining, drilling, and agriculture were being automated and industrialized to require fewer unskilled workers.

These big socioeconomic swings were powerfully disruptive of the rural and Appalachian communities, and not all communities could cope. For some, retaining a Jeffersonian ideal of civic institutions in a community with some ethnic diversity and without broad disparities of wealth (Chetty’s recipe for success) continued to support the success of young people as they matured and moved away. For other communities, the loss of a civic base and the emergence of “haves” and “have nots” have taken a toll. Factory farming converted farmer owners to tenants; the demise of unions in the extractive industries made the work more dangerous and the wealth less widely shared. And then, just as the Great Recession hit, cheap gas turned coal into a dying business.

Rebuilding Appalachia could be a model for a new initiative that broadens the economic base and preserves unique cultural values of rural America. Marian Conway makes this point in an NPQ newswire, “The Environment as a Moral, Class, and Human Rights Issue.” Perhaps wise leaders can reframe federal assistance as a form of reparations for the demographic, ecological, and cultural damage done by a century of removal of agricultural products, coal, gas, timber, and young people.

Social psychologist Kurt Lewin laid down some guidelines for what was called “cultural reconstruction” in the midst of World War II. Dr. Lewin was looking forward to the need for reconstruction in his native Germany at war’s end. In an essay, Lewin wrote:

It seems feasible and natural to build up group work around the feeding of Europe after this war in such a way that the cooperative work for reconstruction would offer a real experience in democratic group life. It would be possible to reach a large number and wide variety of age levels in this and other works of reconstruction.

Think of the Marshall Plan as a direct extension of Lewin’s imagining, and then consider the failure of Lyndon Johnson’s community action agencies, which devolved from civic engagement to the dole.

The U.S. is already doing the feeding and providing the healthcare in much of Appalachia, but it fails to foster what Lewin called “the cooperative work for reconstruction.” This work, as envisioned by Lewin and the many others working from a similar conceptual base over the years, has to do with the common envisioning, planning, and implementation of our collective futures. It is basic organizing done well and owned locally, and that should be the core of the work of many nonprofits.—Spencer Wells