March 25, 2019; New York Times and Slate

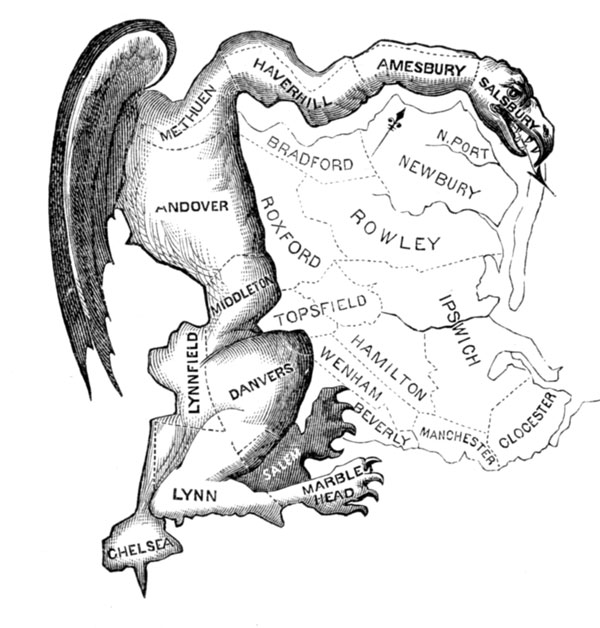

When you vote, your expectation is that your vote will count. But depending on just how the lines are drawn for your congressional districts (both state and national), it’s a question just how much meaning your vote has. For years, politicians on both sides of the aisle have manipulated the boundaries of districts to favor one party or another, pushing voters of one persuasion into one area and creating some most interesting (and confounding) patterns of political districts. The result: In the House of Representatives—even in “wave” election years, when there is a large shift from one party to another—reelection rates exceed 85 percent. In non-wave years, they are typically closer to 95 percent. Even in 2018, clearly a “wave” year, 91 percent of incumbents who ran for reelection to the US House of Representatives kept their seats.

Race has also come into play as boundaries are drawn, and NPQ has addressed the federal court and Supreme Court cases in the last few years that have ruled that racial and partisan gerrymandering is unconstitutional.

This week, the issue of gerrymandering returns to a Supreme Court that had been reluctant to make a concrete decision on this difficult issue. But the Court has some new players now, with the addition of Justice Brett Kavanaugh flanked by Neil Gorsuch, and this leaves Chief Justice Roberts as a possible swing vote on what may or may not be a partisan issue.

The justices of the US Supreme Court have shown great reluctance to wade into these waters, not wishing to be seen dipping their toes into the politics of what should be dealt with by Congress and the states and fearing the potential to over-politicize the Court. The 2017 and 2018 cases were sent back to the lower courts and the states for resolution; obviously, not a successful move, since the Supreme Court finds itself again with the issue of gerrymandering in its lap.

On their face, the two partisan gerrymandering cases the court is hearing do not look like they should break along party lines. In one case, Rucho v. Common Cause, good government groups Common Cause and the League of Women Voters are going after North Carolina Republicans for explicitly drawing congressional district lines to help Republicans capture 10 of 13 seats. In the other case, Benisek v. Lamone, good government groups such as the Brennan Center are siding with Republican voters who have challenged Maryland Democrats’ decision to gerrymander a Republican district to give Democrats a 6–1 congressional advantage in the state. Political scientists have weighed in on both cases to say that technological advances in data technology have allowed for more sophisticated gerrymanders, giving states in the upcoming 2020 elections the ability to draw district lines that will be so effective they can withstand even wave elections that should sweep entrenched incumbents out.

And yet redistricting, like so many other election reform issues, has itself become another partisan issue, with Democrats much more likely to support reform and Republicans more likely to want to leave the question to the political branches. Former Obama Attorney General Eric Holder has raised considerable sums for a Democratic effort to fight Republican redistricting efforts, and former Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker has agreed to head a Republican group in response to Holder.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

How are judges to distinguish between an acceptable map and one that’s gerrymandered? It would seem that no map could be drawn without some bias. This is demonstrated in North Carolina, where the map in dispute in the SCOTUS case bisects the largest historically Black state university in the country with five dorms in one district and seven in another. Not all cases are so distinct, but the voting outcomes are. Is this a judicial issue, or should it be back in the hands of lawmakers who created these maps in the first place?

Modern technology seems to offer some solutions outside of the judiciary and legislation, as NPQ and others have pointed out.

Social scientists have devised a host of new yardsticks in recent years for gauging partisan leanings in maps. Perhaps most important among them is that advances in computing now permit experts to randomly generate thousands and even millions of hypothetical maps, all drawn using the same criteria, that can be compared with the maps challenged in gerrymander trials. Mathematical formulas can then calculate whether a challenged map is part of the pack in its partisan tilt or is at the extremes—a “statistical outlier,” in redistricting parlance.

That already has been done in the federal trial challenging the North Carolina gerrymander. There, an expert witness for the plaintiffs randomly generated 3,000 simulated congressional district maps using the same demographic data as the official map that has regularly awarded Republicans 10 of 13 seats.

None of the 3,000 gave the party more than nine seats.

The Supreme Court will hear these two cases and arguments will be put forward. Some Justices will be uncomfortable with the partisan and racial nature of this issue. Some may not. Will this be another 5-to-4 decision about fairness and equity? Will there be a swing vote? It will be difficult to kick this one back to the lower courts or the legislatures again—although one should never count this possibility out. But it may finally be decision time on gerrymandering.—Carole Levine