Neftali / Shutterstock.com

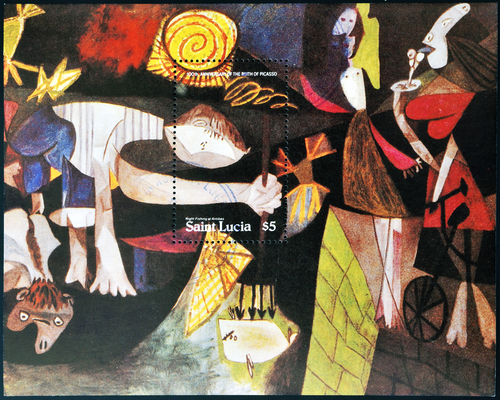

You either like or dislike Picasso’s work. That’s your personal view or attitude. But art experts judge Picasso as a seminal artist, a game-changer. You hire a lawyer and pay attention to what she says without wasting too much time offering your ill-informed or uninformed opinions about the law. You hire a doctor and don’t second-guess her surgical methods.

There’s a substantive difference between personal opinions that are not based on expertise and informed opinions, which are based on expertise and a body of knowledge and research. Unfortunately, the nonprofit sector seems full of opinions, and far too many are the bad kind: ill informed and/or uninformed.

For example, say your boss doesn’t like the direct mail letter that you wrote. Your letter is based on the body of knowledge and research from people like Mal Warwick, Sean Triner, Jeff Brooks, Jerry Huntsinger, and Tom Ahern. But your boss isn’t “comfortable” with the letter. In his opinion, the letter doesn’t represent the agency well. Who is the fundraising expert at your agency? Not your boss. (And not your board chair or any of your board members either, by the way!) The expert better be you!

Here’s another example. Your board chair, the bank CEO, runs a tight board meeting. She uses the executive committee (which I’m on a mission to destroy, as I have previously written here) to work through all issues before the board meets. Committees report at each meeting. Board dialogue is limited, as my article “Conversation is a Core Business Practice” points out.

As the executive director, you’ve studied the body of knowledge about governance by attending workshops and reading books and research. You also serve on boards. You’re trying to improve governance at your agency – and that certainly includes board meetings. But your board chair graciously chuckles and says, “I’ve served on more boards than you are old. We’ll stick with my tried and true approach.”

Your board chair thinks her years of board service make her an expert in governance and board development. But she’s wrong. Experience alone doesn’t make her an expert. She needs the book knowledge and the research findings.

Opinion-Based Approaches and Lousy Fundraising or Governance

There’s something else that is disturbing about the use of personal opinions and experience in fundraising and governance. Too often, this approach leads to lousy fundraising and governance that other people observe and participate in…and then copy.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

For example, I find that most boards are somewhat (or largely) dysfunctional. I’m talking about the supposedly sophisticated boards with their supposedly knowledgeable staff and their powerbroker board members. Yes. Most boards are not that good. And it’s not just me who says so. Read the research from for-profit and nonprofit sector publications like Harvard Business Review and, yes, Nonprofit Quarterly, and and and…

Here’s another example. Let’s say one’s fundraising isn’t doing all that great. Why? Well, there’s the donor retention crisis that began before the 2008 recession. There may be a lack of knowledge about donor satisfaction. Other issues might be insufficient personal face-to-face solicitation, or lousy donor communications. But too many fundraisers don’t know or follow the body of knowledge and research. And those that do too often get stymied by bosses and boards with personal opinions.

Stop Living in a Fact-Free Zone

There’s another problem we have in our work (and in our society at large): fact denial and fact deniers. As Eric Foner stated in a great commencement address for doctoral candidates at Columbia University, “We live in a world where scientific knowledge is subordinated to political and religious dogma, where intellect and expertise are denigrated as elitist, where demands proliferate that history be taught as an exercise in national self-congratulation, not critical self-examination.”

Instead of acting as critical thinkers – learning the body of knowledge and using good research – too many people assert their personal opinion. And these people demand that all others accept the validity of their personal opinions. In fact, parts of our society (and our enterprises, no matter the sector) too often deny facts and assert opinion. Global warming anyone? As Chris Mooney wrote in a marvelous Mother Jones article, there’s actually a “science of why we don’t believe science.”

We need to stop the uninformed and ill-informed opinions and the fact-deniers! Uninformed or ill-informed personal opinion has an impact on the work we do. These opinions – too often promoted by whichever “powers that be” control your life or our agency or our world – stop forward progress. These opinions distract us from the right work and they compromise integrity.

The job of good and competent professionals – and ethical leaders – is to graciously and forcefully disengage from uninformed and ill-informed opinions.

On the April 9, 2012 edition of Seth Godin’s wonderful blog, Godin writes, “Is everyone entitled to an opinion?” He answers, “Perhaps, but that doesn’t mean we need to pay the slightest bit of attention. There are two things that disqualify someone from being listened to:” “lack of standing” and “no credibility.”

You and I need to pay particular attention to “no credibility.” As Seth notes, “An opinion needs to be based on experience and expertise.” So you and I better acquire and maintain that expertise and experience.