March 18, 2019; New York Times

NPQ has repeatedly suggested that large universities need to play nicer with others when it comes to providing for the health and well-being of surrounding communities. This story exemplifies the kind of behavior that can stoke resentment.

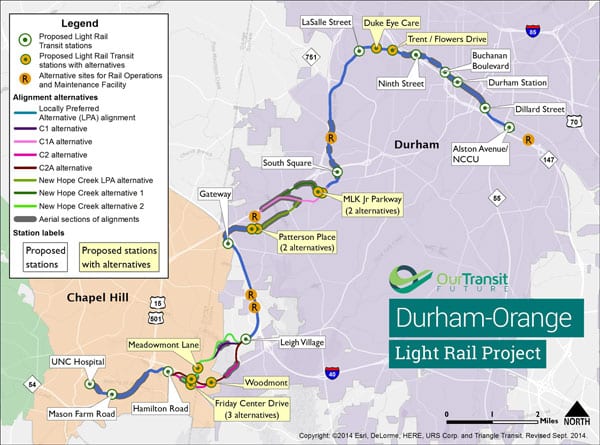

In the Triangle Park region of North Carolina, a 17.7-mile light rail line that “could combat gridlock by linking Durham and Chapel Hill, home to the University of North Carolina, and would provide access to three major hospitals as well as the historically black North Carolina Central University in Durham” seemed to be moving full speed ahead, with taxpayers in both Durham and Orange counties voting in favor of assessing a sales tax to pay for it—until Duke University put on the brakes.

“You have poor and working-class black people who would like to get to better employment in another location, and a whole community collaborating to make this happen, and you have Duke with veto power,” notes Kevin Primus, once a manager of Duke’s men’s basketball team. Primus adds that Duke’s rejection of light rail reinforces the school’s reputation among blacks like himself of being “the plantation.”

For its part, Duke says that the light rail line would interfere with its ability to conduct medical research. As Richard Fausset in the New York Times explains:

Duke officials are adamant that their objections to the project are serious and insurmountable. They said construction vibration and electromagnetic interference from the trains might affect sensitive research equipment at Duke’s sprawling medical campus, which the train line would skirt. And they are concerned about the project’s impact on the underground utilities that serve the medical center—and the threat of new lawsuits.

In their official rejection, administrators said the project, as proposed, would “jeopardize community health, public safety and the future viability of our enterprise.”

Fausset adds, “Duke officials have said they are not opposed to light rail in general, only to this specific project.” In short, the threat of construction vibration and electromagnetic interference made them do it. On its face, Duke’s reasoning sounds plausible—but a little bit of history makes Duke’s argument seem more dubious. To understand, one should look at another university that raised the same argument nine years ago.

The place was College Park, Maryland. At the time, a light rail line was planned to cross the University of Maryland campus, but the university opposed its construction “because of concerns of electromagnetic interference which could potentially affect delicate research equipment in buildings close to Campus Drive.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Shortly afterward, however, the very same school became a leading advocate for what is now known in metro Washington as the Purple Line. Had a new non-vibrating technology been invented? Hardly. What had changed was the university’s leadership. Daniel Mote stepped down and Wallace Loh took his place.

Six years later, Loh explained the university’s change of heart. “We had the opportunity to have that Metro subway underneath Stamp Union, or where Stamp Union is now,” Loh said to the college’s student newspaper, The Diamondback. “We turned it down—we, meaning our predecessors. […] Georgetown also turned it down—both to our regret. So now we have to spend more time, more money, to rectify the mistakes of the past.”

As for the technical issues, Loh said,

The aesthetics, the vibrations, the safety, and the electromagnetic interference with experiments—these are all fixable. The answer is not “Don’t do it.” It’s “Do the technical solutions for it.”

The Purple Line in College Park is being built and slated to open in 2022, and yet the same dubious argument advanced a decade ago has resurfaced here. A memo from the Durham transit group notes that College Park is not unique. Indeed, the transit organizing group, called GoTriangle, says that it has “a list of 20 medical centers around the country with rail systems in close proximity.”

Given that similar technical issues have been managed successfully by so many other communities, what are Duke’s true motives? In the Times, Fausset acknowledges that “some critics wondered whether Duke was using its stated concerns as an excuse for other, hidden worries about the train.” For instance, the Duke statement mentions “public safety”—often coded wording for fears that transit might bring low-income people of color into wealthier white areas. Certainly, if this were the case, it would not be the first time light rail opposition has been so motivated.

Meanwhile, Duke’s action has provoked widespread condemnation. Wib Gulley, a former mayor of Durham, likened Duke’s decision to reject light rail to its 1969 decision to call in the police “to gas and beat students” amid civil rights protests.

Fausset also notes that Mark-Anthony Middleton, a black Durham council member, advocates using eminent domain, calling it “the unsexy part of the work of racial equality.” Middleton tells Fausset that the light rail line “would serve predominantly black Durham neighborhoods that were badly hobbled in decades past by urban renewal projects and highway construction.”

Is there a solution to the impasse in Durham? That remains to be seen. Perhaps Duke administrators should visit their colleagues in College Park.—Steve Dubb