January 9, 2013; Source: Fast Company

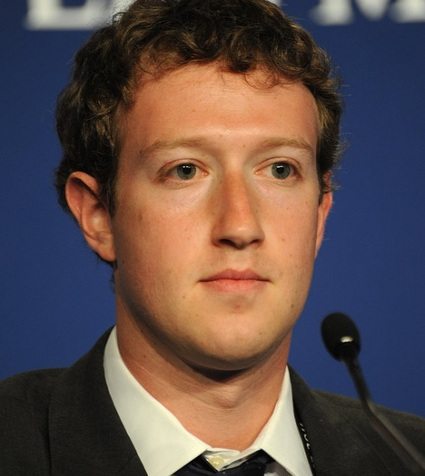

Anya Kamenetz of Fast Company has a truly devastating article about how Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg and Newark, N.J. Mayor Cory Booker “stage-managed” Zuckerberg’s $100 million donation. Kamenetz reviewed 96 pages of e-mails between Zuckerberg, Booker, Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg (even though Zuckerberg’s donation was a personal gift, not corporate philanthropy) and others that were released by the City of Newark on Christmas Eve. The city had refused to release the e-mails, citing executive privilege, but a parents group and the American Civil Liberties Union sued and got Booker’s people to reluctantly comply with state law on public disclosure.

The e-mails are an amazing read. Mayor Booker should also be embarrassed by trying to block the public’s right to know about them via his invocation of executive privilege. Kamenetz writes about the planning team’s discussions “to make the donation look participatory…and making sure the billionaires look ‘modest’ and feel ‘special.’” In one e-mail, a public relations person describes the coverage of Zuckerberg’s “modest life,” which is juxtaposed against the unflattering portrayal of Zuckerberg in the film The Social Network.

Our interest in the e-mails is the technical back and forth about how Zuckerberg’s and Booker’s people made the donation work, particularly the efforts, encouraged by Sandberg, to have “citizens put in funds to help match Mark’s money” as well as recruiting big name donors. The team debated platforms for soliciting and processing small donations (DonorsChoose, PayPal, Google, Kiva, Square, Amazon Payments, etc.), consistent with Sarah Ross’s (from Ashton Kutcher’s company, Katalyst) e-mail input that “it’s bad positioning for Mark if only higher end donors are able to contribute to the matching funds in large chunks.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

NPQ is equally interested in Newark’s efforts to recruit big name, big money donors. Among the names popping up in the list were Oprah Winfrey, the Eli Broad Foundation (which apparently wanted to condition a potential contribution on who the superintendent of schools would be, not unlike its position regarding support for the state programs of Gov. Chris Christie), John Doerr, Warren Buffett, and Bill Gates. Gates gave $3 million for “teacher professional development” and discussed the installation of “panoramic cameras” to monitor and videotape teachers with 360 degree visual and sound coverage to identify what they did well and not so well.

There is even some odd e-mail commentary from Mayor Booker’s fundraising advisor, Bari Mattes, stating that “Mark’s money is not going in to classrooms,” though it is unclear exactly what that means in relation to a donation to the Newark schools. In all fairness, these kinds of interactions between Booker’s and Zuckerberg’s people would have occurred in any city where a philanthropist was waving around a check for $100 million. It is entirely logical that there would be involvement of PR people on all sides to give the donor the press coverage he or she wanted, to burnish resumes and overcome previous negative publicity, and to avoid making statements to trigger opposition from educators and parents.

What should concern readers, however, is the extent to which the City appears to have been willing to let donors’ concerns drive policy decisions. Kamenetz suggests that the “smoking gun” in the story is Broad’s desire to condition a grant on the selection of the schools chief. The person chosen, Cami Anderson, is identified in the article as a former executive director of Teach for America; she is also a former chief program officer of New Leaders for New Schools. Late last year Anderson, announced that she would use some of Zuckerberg’s money to pay for teachers’ salaries and bonuses in contract renegotiations, ultimately using about $50 million of the Zuckerberg contribution, much like former D.C. Schools Chancellor Michelle Rhee did with $64 million in foundation and private donations.

Reading the e-mails, the language and the people involved are very much part of the school reform movement nationally that Booker explicitly lauds in one e-mail. This is consistent with Booker’s 1999 co-founding of Excellent Education for Everyone (E3), which promotes charter schools and vouchers, though in his mayoral campaigns, Booker has disassociated himself somewhat from the voucher side of E3.

The Newark schools need $100 million, but Newark voters and Newark’s parents need to know who is making what decisions for the education of their children. Big money, whether from Zuckerberg, Broad, or Gates, shouldn’t trump the democratic process.—Rick Cohen