May 8, 2017; Journal of Blacks in Higher Education

Earning a college degree is a crucial step up the economic ladder. For those struggling to escape poverty, a college education may be the only way out. And, if that degree is from an elite university, the benefits are so much larger. Yet, according to a new study from the Georgetown University Center on Education and Workforce, academically qualified low-income high school students are having a difficult time being admitted at many select schools.

As an introduction to their research, Anthony P. Carnevale and Martin Van Der Werf set the important context for their work.

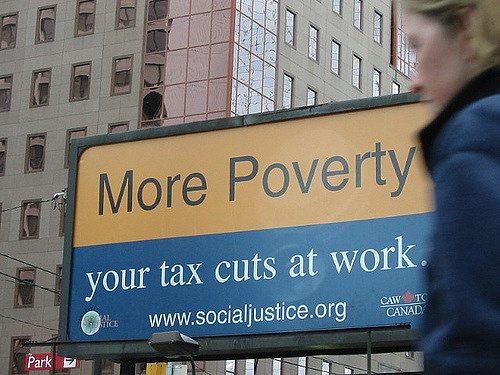

Low-income students have rarely had much success on college campuses. Although college enrollment rates generally have been rising for all population groups, enrollments have risen the least for low-income students. The disparity in graduation rates by economic class is stunning: more than half of students from the top quartile of family income finish college, but fewer than one in ten from the bottom quartile do. The growth in wealth inequality since the 1980s is mostly due to this postsecondary education gap. By and large, young people who earned college degrees grew wealthier, while those who did not grew poorer—especially as workplace demand in the new technologically-focused economy has shifted towards college-educated workers.

Attending a more select college is not only a matter of prestige and gaining networking opportunities; attending a selective college makes earning a degree much more likely. Graduation rates at more selective schools are significantly higher (82 percent) than less selective four-year colleges (49 percent). Only 12 percent of students who begin their college careers at community colleges end up with a four-year degree. The Hechinger Report described a significant number of high school graduates who are losing a chance to take this important step out of poverty because elite universities have not made space for them: “Most low-income students end up at community colleges and regional public universities…but some 86,000 annually score on standardized admission tests as well as or better than the students who enroll at the most selective universities and colleges.”

While standardized tests may not be the being the best way to evaluate readiness for college, the study did conclude that low-income students whose scores are equal or better than the average score of all current selective school students graduate at the same rate as well. Low-income students with the same test scores who attend general admission schools have a graduation rate about 50 percent lower.

Carnevale and Van Der Werf challenge policymakers to require that select universities enroll a greater number of qualified low-income students, up to at least 20 percent of their student bodies. Of the 500 most selective schools, 163 do not currently meet this threshold. At this level, an additional 43,000 low-income students would have a seat in selective college classrooms. This target is reachable; UC-Berkley, Columbia University, UCLA, and Vassar are among the list of schools whose low-income student enrollment exceed 20 percent.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

The report notes that Pell Grants, the federal program that provides college scholarships for low-income students, are not large enough to cover the tuition at most elite schools. Universities will need to re-budget their resources to increase low-income enrollment.

Universities and colleges usually don’t have uncommitted funds in their budgets. Colleges that have successfully allocated more money to financial aid typically had “strategic cost containment plans” that allowed them to reallocate money from one area of their budgets to another. An increased enrollment of low-income students could have other budgetary impacts. Colleges may have to offer more in the way of academic and non-academic counseling. Also, if they take on more Pell Grant recipients, they may have to offer additional aid for housing and food.

It’s important to note that though the study uses standardized test scores as a metric of college eligibility, comparable test scores alone do not make students equal candidates for admission. Harvard’s acceptance rate is 5.4 percent; factors other than grades and test scores have to be considered to narrow the pool that far. These factors can be another barrier for students who don’t have access to a full range of extracurricular activities or connections to alumni who can write recommendation letters. The equity-versus-equality debate in higher education is a tense one, in part because of the enormous advantage given to graduates of select universities and the comparatively limited places available in them.

Is the good of giving thousands of students a chance of a better life worth asking this of all universities whose tax-exempt status requires them to act for the public benefit? In proposing a 20 percent goal, the study’s authors think it is.

Although there are many tradeoffs to consider, perhaps the most important is that the best colleges and universities have the opportunity to serve more low-income students than they are currently. These students now go to colleges from which they have only about a 50-50 chance of graduating. Enrolling them at colleges from which they have close to an 80 percent chance of graduating could go a long way toward advancing equity in this country—by giving students in poor financial circumstances a far greater chance of succeeding.

Many elite universities have robust financial programs that make it easier for low-income students to attend, as NPQ has reported. What is the next step for them to take in making college accessible to all qualified students?

If closing the wealth gap matters, then closing the elite university low-income student gap needs to be a part of the solution. Some members of Congress seem to agree as well having introduced a bill that would penalize universities with the lowest proportions of low income students.—Martin Levine