Environmental justice is the frontier of the environmental movement in the US and around the world. The field, scholarship, and advocacy instill the principle that biodiversity, social diversity, ecology, and health are interconnected. The nitty-gritty is democratic systems change—no less than sustainable realignment of the economy and the environment, health for all, and shared prosperity.

Environmental justice takes on the racial, social, and economic root causes of disparities. Attention paid to race, gender, culture, and class is critical to ensuring that those who are hardest hit by pollution can access opportunities, participate in policy decisions, and benefit from investments. In sum, environmental justice is the multicultural dimension of environmentalism.

The focus of Big Green environmental and conservation groups that emphasize biodiversity and protecting wildlife and natural habitats like oceans, rainforests, grasslands, and desert ecosystems is different, however. Who gets included as part of “Big Green” is not always consistent, but helpfully the nonprofit Center for Media and Democracy’s SourceWatch identifies 10 lead organizations. These are: Defenders of Wildlife, Environmental Defense Fund, Greenpeace, the National Audubon Society, the National Wildlife Federation, Natural Resources Defense Council, The Nature Conservancy, Sierra Club, The Wilderness Society, and World Wildlife Fund. (A more extensive list of the 25 largest environmental groups is available here.)

Compared to the environmental justice movement’s multiplicity, Big Green leaders, staff, members, and affiliates often remain largely white. Likewise, grappling with equity in programming and policy advocacy is in short supply. Analogous to how equity, diversity and inclusion is too often treated in the workplace, Big Green groups have normalized the term “environmental justice,” but have far from fully integrated its more extensive frame, which refers to the need to not only change the boundaries of environmental policy, but reconceptualize what counts as the work of environmentalism and what it means to be an environmentalist.

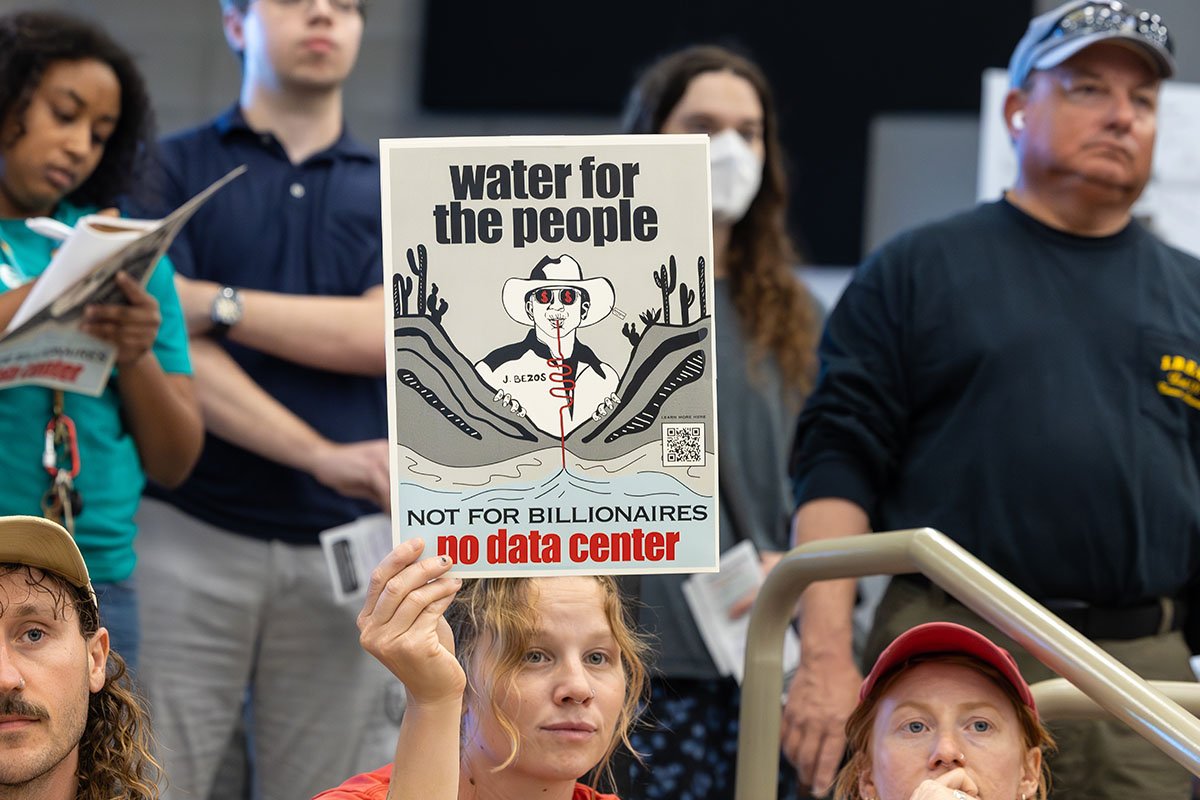

Friction between green groups and environmental justice groups is longstanding—with environmental justice groups often accusing Big Green groups of elitism, racism and, valuing the wilderness more than people. This tension continues to play out locally and in policy debates. Working across differences may be harder in the near term, but, if the hurdles of difference can be negotiated, the potential for collaboration to deliver much greater returns is great.

Defining Terms

Imagine an environmental movement that breaks new ground by tackling equity and the overlapping social and physical determinants people of color and others face on the frontlines of pollution and climate change. While environmentalists can surely count gains made for the planet, more can be gained by grappling with root causes instead of symptoms. Environmental justice is the diversity shot in the arm that Big Green needs.

There is no one universal definition of environmental justice, but the following well-accepted description draws from the Principles of Environmental Justice.

“Environmental Justice (EJ)…refers to those cultural norms and values, rules, regulations, behaviors, policies, and decisions to support sustainable communities where people can interact with confidence that the environment is safe, nurturing, and productive. Environmental justice is served when people can realize their highest potential…where both cultural and biological diversity are respected and highly revered and where distributed justice prevails.”

Professor Bunyan Bryant, University of Michigan, Environmental Justice: Issues, Policies, and Solutions

This is a Peoples’ Agenda—from the bottom up—rooted in political, human, and civil rights, and driven by local grassroots organizing across disciplines and geography. Percolating into mainstream public consciousness, this reframing weaves a social change narrative grounded in fairness for all. Big Green’s traditional ecological, nature, wildlife, and outdoors mission could provide potentially complementary common ground.

Exploring Origins

Some environmental groups have roots in the late-19th century conservation movement (such as the National Audubon Society and the Sierra Club), while others that formed in the mid-20th century might cite Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, wildlife extinction, and the Cuyahoga River fires as inspiring their founding. The environmental justice field arises a bit later, from a series of racial discrimination driven protest actions in the US, starting in the early 1980s.

Leaders of color galvanized people across the country, launching the new justice paradigm joining racial equity, the environment, and health. African Americans’ opposition in Warren County, North Carolina is a widely cited watershed—for the first time in US history, citizens were jailed for trying to stop a landfill in a civil disobedience action.

In 1991, hundreds of delegates representing communities of color and indigenous peoples gathered at the First People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in Washington, DC. The seventeen Principles of Environmental Justice that came out of that event pinpoint concerns ranging from food, renewable resources, and the targeting of noxious facilities and toxic sites, to social and economic issues like jobs, health care, education, and access to services. Groundbreaking studies, from then to now, corroborate why equity, sustainability, and inclusive community engagement are core environmental justice tenets.

When President Bill Clinton took office in 1993, thousands of activists joined in the coast-to-coast campaign I facilitated while at the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, urging a federal response to unequal protection under law. The campaign resulted in Executive Order 12898, Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations. The Order boosted the validity of the field and gave these grassroots efforts added legitimacy, visibility and momentum.

Changing Policies

The environmental justice movement raised public awareness, nationally and internationally, about discriminatory impacts, and the social, legal, and material practices that create them. As a result, over the past few decades, government policies and corporate processes changed.

Candidates in the 2020 US presidential electoral race are injecting the words and more. They are proposing federal solutions including new legal protections, disproportionate impact equity scoring, and rebooting the national Council on Environmental Quality’s focus.

In the states, climate change is front and center. Washington’s new clean electricity law contains energy resilience measures, requires equitable distribution of benefits, and cumulative impact analysis to reduce burdens on the vulnerable. Grassroots groups were essential in the enactment of California’s landmark climate laws and the 25-percent reserved revenues for job creation and investments in disadvantaged neighborhoods.

In South Dakota, the fight over the Keystone XL pipeline permit and the protests on Standing Rock Sioux lands exemplify the power of environmental justice pushback. This struggle is about infringement of indigenous collective political rights and blocking threats to the climate, cultural resources, protected waters, human health and safety and wildlife. Indigenous leaders and their attorneys battle back and forth in this struggle against the US government and TC Energy. Whatever the legal outcome, the fight is a worldwide game-changer, invigorating and rallying people from all walks of life.

International impact stands out in the Global Atlas of Environmental Justice, which maps thousands of local stories of resistance against inequitable distribution of burdens, amenities, and damaging projects, from land thefts, deforestation, and mines to refineries and poisonous waste sites.

Battles fought since the 1980s illustrate the potency of environmental justice and the spotlight gained from government, academics, policy makers, the media, and the public. The fight for rights and equity is turning over the popular assumption about environmentalism’s elitism in favor of championing the right to a clean, safe, and healthy environment regardless of race, financial status, or zip code.

Bridging Disciplines

Hurricanes, floods, famines, disease outbreaks, and pollution fill the news with graphic evidence about the intertwined human and natural environment and the health of the planet. This denominator could ally the environmental justice movement and Big Green—what is at stake is nothing less than saving the earth. Potential synergies and the urgency of climate change outweigh the obstacles to collaborating. The solutions that prioritize benefits for people who are marginalized will benefit everyone and nature. It is time to turn the page.

Nascent collaborative climate efforts bode well because the economics of decarbonizing the globe is turning into a dominant issue worldwide, in the 2020 national elections, and for Europe’s Green parties. Greenpeace, for example, endorsed the Vision for Black Lives platform, which is significant because the biggest environmental groups have historically avoided mentioning race—one of the chief critiques made by environmental justice advocates of Big Green groups. Greenpeace acknowledges the Black Lives climate agenda, “the inextricable connections between environmental and racial justice” and commits to “work together to confront the unjust structures and exploitative industries targeting Black communities.”

President Barack Obama’s Clean Power Plan is another example. The campaign to inject equity is a testament to community driven, cross-sector information exchange efforts with governmental agencies and Big Green. Although partnerships did not fully form, the Building Equity & Alignment for Impact Initiative (BEA) documents the leadership of people of color, the alignment barriers posed by differences in comparative size, staffing, and funding, and the promise for such coalitions.

Merging ecology, nature, and the outdoors with environmental justice activism will be complex. Coming together involves respecting the significance of community place, history, and collective lived experiences, as well as displaying a willingness to co-prioritize equity factors and strategically incorporate the views of those closest to the solutions.

Creating Alliances

Expanding environmental concerns beyond species and habitat to incorporate equity and inclusion is a big challenge, but the upside is a menu of collaborative options. The partnering stage is set, in part, because green groups realize the mounting significance of racially and culturally diverse US majorities and young voters in frontline neighborhoods who support governmental climate and pollution control interventions.

EQUITABLE ALLIANCES

I. Endow development of inclusive, trusting, reciprocal relationships

II. Respect the leadership of people of color, women, different cultures, identities, and faiths

III. Plan to surmount differences in organization scale and funding

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

IV. Partner, campaign, share expertise and co-fundraise respectfully

V. Embed strategies, best practices and investments that support resiliency for distressed communities

Recently, over 70 green groups and environmental justice organizations endorsed the Equitable and Just National Climate Platform, part of the Climate Forum, a coalition that is mobilizing around a national policy strategy. It was encouraging to see among the platform co-authors and signatories not just environmental justice groups, but two prominent “Big Green” groups—the National Resources Defense Council and the Sierra Club. Last January, over 600 cross-sector organizations endorsed climate change recommendations in an open letter to Congress.

Another plus is networks that support local climate and energy organizing and policy advocacy like BEA, Indigenous Environmental Network, the Climate Justice Alliance, Environmental Justice Leadership Forum, and the Center for Earth, Energy and Democracy. Scholars at institutions like the University of California (UC) Berkeley, UC Los Angeles, University of Michigan, the New School, Texas Southern University, and Dillard University add to the thought leadership.

Philanthropy, for its part, slowly is beginning to address the legacy of the sizable resource disparities between Big Green and environmental justice groups. Most philanthropic funding still sits within white-led nonprofits and conventional environment, conservation, health and development silos. But some larger foundations—like Kresge, JPB, and Hewlett are stepping up. Newer sources dedicated to reinforcing the grassroots like the Windward Fund, The Solutions Project, and the Just Transition Fund are up-and-coming.

These are promising developments for fostering equity, especially scrutinizing the biological and physical features of socio-economic systems, confronting cause and effect relationships and building power. In the inset box, I outline five coalition building best practices shaped by my environmental justice practice in the field.

Environmentalism 2.0?

The bold stance of environmental justice on equity issues that aren’t traditionally recognized as green, the environmental movement’s genesis, and the systemic lack of racial and cultural diversity in many Big Green organizations are three big obstacles to unifying the two movements.

The history and tradition of racial exclusion that shaped the environmental and conservation movement began in the 19th century, when eugenics, enslavement of Black peoples, Jim Crow, the genocide of Native Americans, and sexism were the rule of law and had broad legitimacy in elite society. These views are reflected in the writings of such noted conservationists as Jackson Turner, Madison Grant, John Muir and slaveowner John James Audubon.

Wilderness areas and public policies based on their philosophies shifted resources and access along lines of race and economic status and, until the end of the 1980s, wilderness studies mostly excluded people of color. The environmental movement must confront the racialized ideas of the founders, the many ways in which the US government misappropriated and segregated open space for the exclusive use of whites, and the validity of the scholarship.

Organizations must change on the inside before they can change on the outside, which makes the whiteness of the green groups’ leadership and workforce another challenge. Environmentalists that won’t embrace fairness for people of color, women, and different cultures in the workplace, and the inclusion of community voices and concerns, face irrelevancy as these populations and younger generations gain numbers and power.

The obstacles between the two movements are persistent. Unification would require Big Green to reconceptualize values and deeply embedded customs and roles. Twenty-nine years ago, the Southwest Organizing Project authored the seminal letter challenging the Group of Ten’s whiteness and biased programs. The singularity of environmental justice and the slow pace of change since then means that in the near term a merger of values is infeasible. Instead, the two can—and should—meet minds, identify, and collaborate on aligning crucial mutual goals.

In 1970, more than a million people came out for Earth Day. It was then that Senator Ed Muskie, one of the primary architects of US environmental laws, explained, “Man’s environment includes more than natural resources. It includes the shape of the communities in which he lives: his home, his schools, his places of work.” After this oft-cited record-sized mass mobilization, this stance lost fire.

It is uncertain whether environmentalism will retrieve that spirit, but today there are real opportunities for solidarity. The stakes are high, and the opportunities for working together, on matters such as healthy communities, Just Transition for workers and the Green New Deal are plentiful. We cannot safeguard people and the planet if we are not courageous enough to appreciate diverse ideologies, commit to reciprocal goals, and invest where it counts.

References

Ferris, D., “Environmental Justice: Continuing the Dialogue,” Society of Environmental Journalists, Third National Conference, Duke University, Durham, NC, October 21-24, 1993.

Ferris, D., “A Call for Justice and Equal Environmental Protection,” in Unequal Environmental Protection, Bullard, R., ed.: San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1994.

Ferris, D., Hahn-Baker, D., “Environmentalists and Environmental Justice, in Issues, Policies, and Solutions, Bryant, B., ed.: Washington, DC: Island Press, 1995.

Bell, J., “5 Things to Know About Communities of Color and Environmental Justice,” April 25, 2016. Center for Community Progress.

Taylor, D.E., The Rise of the American Conservation Movement: Power, Privilege, and Environmental Protection. Duke University Press, 2016.

Taylor, D.E., Toxic Communities: Environmental Racism, Industrial Pollution, and Residential Mobility. NYU Press, 2014.

Starkey, M., “Wilderness, Race, and African Americans: An Environmental History from Slavery to Jim Crow.” University of California, Berkeley, 2005.

Cushing L, Blaustein-Rejto D, Wander M, Pastor M, Sadd J, Zhu A, et al., July 10, 2018. “Carbon Trading, Co-pollutants, and Environmental Equity: Evidence from California’s Cap-and-Trade Program,” PLoS Med 15(7): e1002604

Martinez-Alier, J. T., Temper, L., Del Bene, D., Scheidel, A. “Is There a Global Environmental Justice Movement?” The Journal of Peasant Studies, 2016 v.43 no.3 pp. 731-75.

Kilmanjaro, I., Lopez, A., September 2017. “From the Margins to the Mainstream.” Building Equity & Alignment for Impact.

Rouse, S.M., Ross, A.D., The Politics of Millennials: Political Beliefs and Policy Preferences of America’s Most Diverse Generation. University of Michigan Press, 2018.

Purdy, J., December 7, 2016. “Environmentalism Was Once a Social-Justice Movement: It Can Be Again,” in Science, The Atlantic.

Purdy, J., August 13, 2015. “Environmentalism’s Racist History,” in News Desk, The New Yorker

Sandler, R., Pezullo P., eds., Environmental Justice and Environmentalism: The Social Justice Challenge to the Environmental Movements. The MIT Press, 2007.