March 6, 2018; The Guardian

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has dismissed a civil rights case brought by residents of the small, overwhelmingly Black town of Uniontown, Alabama, against an Alabama environmental agency. The agency had approved the dumping of four million tons of coal ash at a landfill site in their community, reports Oliver Milman in the Guardian. In 2013, several dozen Uniontown residents filed a complaint under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act. In its 29-page letter, the EPA dismissed the complaint on the grounds that there is “no causal connection” between the “alleged harms” and the landfill site.

The group that organized and launched the complaint in 2013, Black Belt Citizens Fighting for Health and Justice, was featured last month on an NPQ webinar in which the organization’s president, Esther Calhoun, participated. With the support of the American Civil Liberties Union, Calhoun and her colleagues last year successfully beat back a $30 million defamation lawsuit launched by the landfill owners that had sought to shut down the group.

Uniontown is a small town of 2,400, located about a half hour’s drive west of Selma. About 90 percent of Uniontown’s population is Black, and about half live below the federal poverty line. The town is also home to the Arrowhead landfill. As Milman explains, “Arrowhead, operated by Green Group Holdings since 2011, sprawls over an area twice the size of New York City’s Central Park, accepting the waste from 33 different states.”

Milman adds that, “The site used to contain a jumble of car parts, electronics, and other discarded items until a flood hit a coal plant 330 miles away in Kingston, Tennessee, in 2008. Over the next two years, the clean-up of Kingston involved shifting four million tons of potentially hazardous coal ash by train to the Arrowhead landfill abutting Uniontown.”

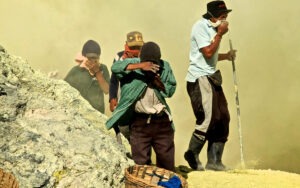

In 2015, Kristen Lombardi reported for NBC News that, “Foul odors, corrosive dust and menacing buzzards have become facts of life for people who live here. Some no longer sit on their porches, grow their gardens or let children play in their yards. In the area abutting the landfill, almost everyone claims to have suffered ill effects—from headaches and earaches to neuropathy.”

In a report published last April, Calhoun told the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy that, “We took pictures [of] the waters coming off the landfill. We had a scientist test the waters that had arsenic in it. We had the EPA come from Georgia to view how close this huge mountain [of landfill] is. Alabama Department of Environmental Management allows sewage water to flow into the creek. The creek flows down, and it goes from community to community. There is sewage that’s contaminating the water, and children are drinking this water.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

EPA’s dismissal of Uniontown residents’ Title VI claim is being met with widespread incredulity. “To say there is insufficient evidence is ludicrous; I just can’t take it seriously,” says Ben Eaton, who has lived in Uniontown for 33 years and is vice president of the Black Belt Citizens community group. “The protection we’ve got from the government is little to none. I can’t help but feel it’s because the population is mainly black and poor. This was forced on us. If this was a white, wealthy community, this would’ve never happened.”

Milman notes that, “Coal ash contains toxins such as mercury and arsenic that can affect the nervous and reproductive systems and cause other health problems. According to the EPA, people living within a mile of unlined coal ash storage ponds have a one-in-50 risk of developing cancer.”

Milman adds, “Residents, already upset the landfill was placed next to a historic cemetery, began to fret that the coal ash would seep out into the air and water. Some stopped drinking the tap water. Many still spend as little time outdoors as possible due to the smell and swarms of flies. A rash of nosebleeds, breathing difficulties, mental health issues and cancers have been blamed upon the coal ash, although the authorities have not conducted any studies to analyze the potential link.”

“The shipping of toxic coal ash from a mostly white county in Tennessee to this rural, poor and most black county and community in the Alabama black belt is a textbook case of environmental racism,” remarks Robert Bullard, a pioneering environmental justice researcher.

Marianne Engleman Lado, a Yale Law School lawyer who represented residents, says an appeal against the EPA was possible but unlikely. Lado notes that the EPA dismissed the complaint because it found the company was operating the landfill within regulatory guidelines. But Lado says that mere compliance with environmental permits should not negate civil rights concerns.

“The decision is frustrating, it’s angering. Uniontown is a classic civil rights situation. How can people trust the government if it can’t even recognize how this enormous facility is affecting the community? It’s mind-boggling.”—Steve Dubb