February 20, 2015; Esquire

Less than 40 years ago, there was a huge shift in crime-related policy. Many believed if we increased the punishments associated with “low level” nonviolent crimes, criminals would be deterred. They were not, and our prison population exploded. Many were poor and unable to post even a $500 bond. The jail population exploded as well. The result: shattered lives and ballooning government deficits. Many believe it is time for a change.

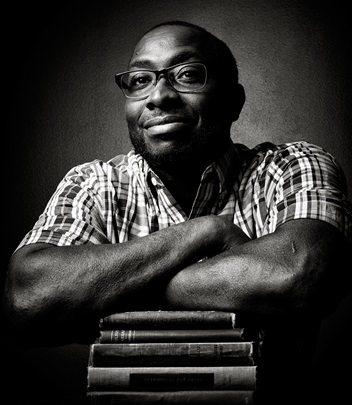

Brandon Crocket (c) 2015

For years, the prison population (excluding celebrity wrongdoers) has been largely invisible in media, but this month, Esquire magazine published a spread of people with their poetry that does not fit the “faceless horde” model. This, we hope, may signal a cultural shift.

On the second Tuesday of every month, a class begins in the basement of a house near the West Side of Chicago. They debate lines and prose. They write poetry full of feelings few have discussed before.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Though the learning is transformative, it isn’t part of a school curriculum. It is lead by a volunteer, Brandon Crockett, and all of the students are former inmates attempting to turn a new page in their lives. Many live in housing provided in the rooms above.

The program is held by St. Leonard’s Ministries, a nonprofit that’s served former inmates for over 60 years. In addition to both temporary and more permanent housing, the organization provides substance abuse treatment, physical and mental health services, and employment training. It serves over three hundred men and women every year. Eighty percent of the men and women completing the program sever the pipeline back to prison and jail, compared to less than 50 percent of all Illinois’ formerly incarcerated.

In the ’90s, few were interested in this impressive success rate, choosing instead to support “three strikes” and other laws extending prison terms for those convicted of nonviolent crimes. Locking them up with little mental health services and fewer employment training programs, the cycle began, and so did spending millions on confining them. Thanks to these practices, many state budgets, including Illinois’, are stuck in the red.

According to a study released earlier this month by the Vera Institute, those in the nation’s jails are more likely to be convicted and to spend time in prison. Even a jail stay of only a couple of days increases the likelihood of broken families and unemployment. Three-quarters of those found guilty are convicted of possession of a small amount of an illegal substance or other low-level nonviolent offenses. Their stay in prison, without access to any of the essential services organization’s like St. Leonard’s provides, costs a minimum of four times more.

Every year, 12 million people are locked up in the nation’s jails. No wonder the MacArthur Foundation, who financially supports the Vera Institute’s work, recently released a request for proposals for a new funding initiative aimed at reducing America’s reliance on incarceration. The five-year, $75 million initiative will fund state and local government programs seeking to develop a more fair and effective justice system.

Breaking the nation’s reliance on jail and prison is the first step. Funding the programs that help these men and women heal and begin living productive lives is the next. To support St. Leonard’s and change the public’s views of those living in prison and jail, Brandon teamed up with world-renowned Chicago photographer Sandro Miller to create an art book of photos and poetry like the excerpt above. The book, Finding Freedom, will become a reality if the Kickstarter campaign launched last week is successful. Miller is best known for his recent project, “Malkovich, Malkovich, Malkovich: Homage to Photographic Masters,” in which he recreated some of history’s most famous portraits using the actor John Malkovich as the subject. It is now running at the Fahey/Klein Gallery in Los Angeles.—Gayle Nelson