March 18, 2018; New York Times and Guardian

Over a progression of painful revelations, it has become evident that the data firm Cambridge Analytica obtained the personal data of tens of millions of Facebook members and used it to create sophisticated targeted messaging for conservative political campaigns. While the conflicting stories about who broke which laws are sure to dominate the news cycle for a while, citizens and lawmakers must ask, what are the bigger implications of this type of power? As concerned members of civil society, how are we to interpret and respond to a public discourse that can be and is ever more manipulated by invisible strings?

Cambridge Analytica is a shell corporation funded largely by radically conservative American billionaire Robert Mercer, who was connected to the firm through Steve Bannon, the Trump campaign’s chief strategist. In 2014, Cambridge Analytica bought the private data of between 50 and 60 million Facebook users without their knowledge or consent from a professor who developed an app that harvested the data, not only of the 270,000 people who downloaded the app, but of all their “friends” as well; he claimed he was collecting it for academic purposes. Cambridge Analytica used this data to create and target users with ads, videos, articles, and other forms of information and “news.” Esquire described Cambridge Analytica’s tactics, saying, “Essentially, the firm would attempt to exploit the user’s profile…to serve them information most likely to sway them a certain way. This information (true or not) would reach users in ads and other content and begin forming an informational bubble around them as they used Facebook and browsed the web.”

Christopher Wylie, a former Cambridge Analytica employee who first reported this issue, called Cambridge Analytica’s campaign a “grossly unethical experiment,” “playing with the psychology of an entire country without their consent or awareness.” Research from Harvard Business School shows targeted messaging doesn’t just influence people by guessing what a particular person might want. It changes the viewer’s perception of him- or herself, making them increasingly subjective to future messaging.

Wylie said, “[Bannon and Mercer] want to fight a culture war in America. Cambridge Analytica was supposed to be the arsenal of weapons to fight that culture war.” Except that a war waged on unknowing citizens is hardly a democratic fight; when messages are coded to appear like facts-based news or to target a user’s weaknesses, the power of individual citizens to make informed choices is diluted. Democratic discourse assumes and relies on people having access to common information; targeted messages fragment that discourse by differentiating messages based on what users are receptive to rather than what is being proposed in a public space.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

In a column for NPQ many years ago, Roger Lohmann explained that nonprofits have a special responsibility to steward the “commons,” in which a sense of mutuality and just social relations arise from shared mission, experience, and knowledge. Undermining that shared experience and knowledge by isolating citizens from direct interpretation of public events, or putting them in an “information bubble,” damages our sense of collective responsibility and our ability to talk to one another across differences, which are crucial for making decisions that affect whole populations. Jeannie Fox pointed out that public trust in institutions like the courts and the media, another aspect of the commons, has declined, which affects nonprofits as mediators in that public and institutional space.

Targeted messaging, whether for advertisements or political campaigns, is not a new tactic; politicians have been doing this for decades. Still, there is a particularly unnerving aspect of knowing that computer algorithms are working to build up an information bubble around individual voters. Computers are exponentially more accurate and efficient at targeting. Do we find this more unacceptable simply because we feel on an unequal playing field, where no amount of caution can protect us from being conned?

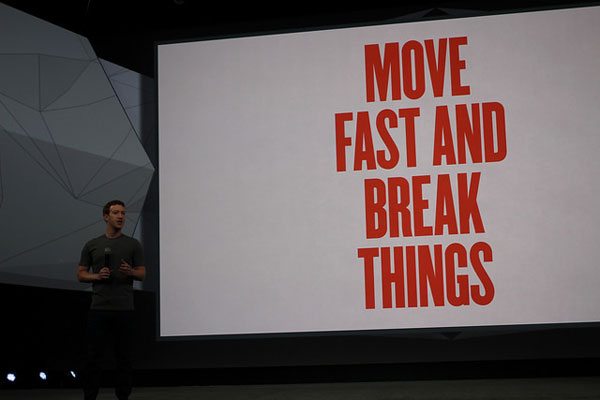

As the scale of the problem has dawned on the public, Facebook has continued to react piecemeal, rather than confront it as a whole. Andrew Bosworth, a VP at Facebook, tweeted, “This was unequivocally not a data breach…no systems were infiltrated, no passwords or information were stolen or hacked.” Technically, that’s true; the fault is not with the program, but with the irresponsible custodianship of people’s data and attention. Facebook’s continued refusal to admit the power of the tool they’ve created or address the underlying issue of public stewardship that goes with that power has lawmakers and citizens alike concerned. Several lawmakers have called for Facebook to testify before Congress to answer this question, and Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey has opened her own investigation into the company’s actions. Facebook has the power to change history by influencing the behavior of their two billion users; can we accept that in a private company?

Some analysts have concluded that Cambridge Analytica’s actual influence on the 2016 presidential election, in terms of the number of voters they convinced, was not very significant, but that isn’t really the point. We should not allow private enterprise to exercise unregulated and disruptive control over public discourse without consideration. Instead, as citizens and stewards of the public square, we have a responsibility to call out and address this threat to democracy.—Erin Rubin