Much like the creation of the telephone or the internet, the advent of artificial intelligence (AI) is changing the very fabric of the society we live in. Not only has AI forever altered the technological landscape, but it also carries monumental and potentially corrosive impacts on the economic, political, and interpersonal terrain that makes up our everyday lives.

Innovators, company founders, and other tech enthusiasts have long tried to sell the public on the idea that AI will create a path to a brighter future. But novel technologies like AI enter a world already fraught by enduring inequities that show up as injustices and indignities for marginalized people. And, rather than creating a more fair and equitable landscape, AI further exacerbates inequalities by codifying power within dominant societal groups.

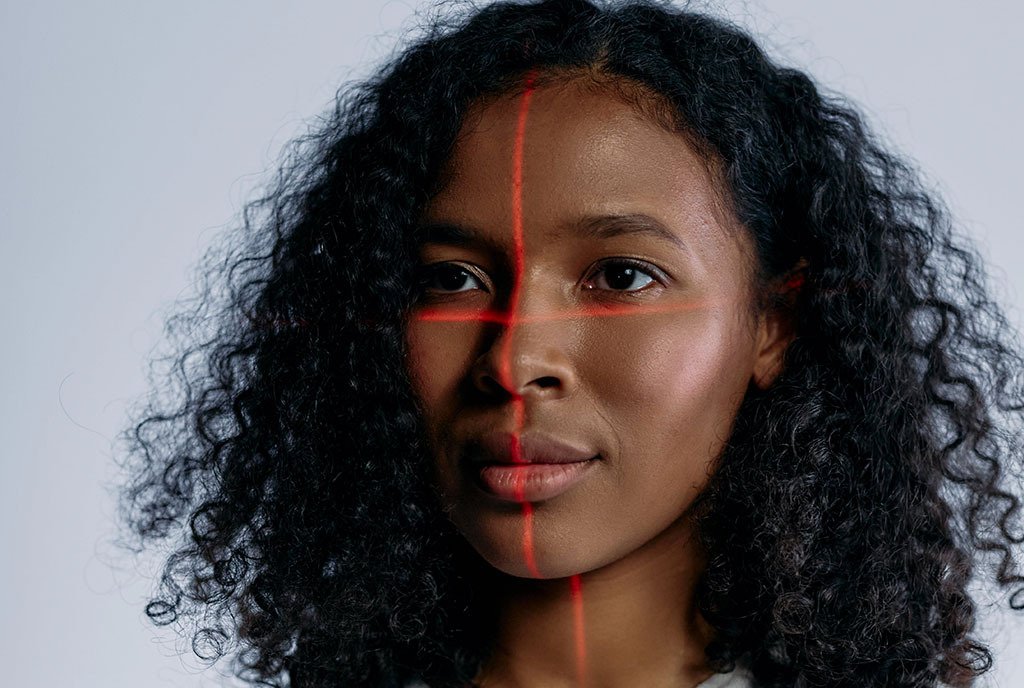

Through testing the technology on faces across gender and skin pigment, studies have explored the degree to which facial recognition technology exacerbates racism, sexism, and their intersection.

Among the most recent and rapid developments of AI is facial recognition technology. Put simply, facial recognition technology is a biometric tool used to identify faces. To identify a face, the tech maps the size and shape of the face and facial features, the distance between those features, and other facets of the face’s appearance. It then compares this map to other faces—typically stored as images in a database—for verification. Problematically, the faces used to train these systems were predominantly those of White men, at the exclusion of other groups. As a result, the systems are largely unable to accurately identify the faces of people of color, women, and especially women of color.

Facing the Research

Through testing the technology on faces across gender and skin pigment, studies have explored the degree to which facial recognition technology exacerbates racism, sexism, and their intersection. In 2018, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) conducted one such study when it tested Amazon’s facial surveillance technology, “Rekognition.” Researchers at the ACLU tested Rekognition on headshots of Congress members, which returned 28 incorrect matches.1 People of color were significantly overrepresented among the false positives, making up 40 percent of those falsely matched with a mugshot in Rekognition’s database, though people of color made up just 20 percent of Congress at the time.

A 2019 report from a government study found “false positives to be between 2 and 5 times higher in women than men.” The same report—which investigated disparities among several racial and ethnic groups, men, and women—revealed that false matches for mugshots were highest for Black women. According to research from the University of Colorado Boulder, since the systems were trained on faces that reinforce the gender binary, they are also deficient in recognizing genderqueer, nonbinary, and transgender people.

More recent studies have confirmed facial recognition technology’s continued inability to accurately recognize non-males and people of deeper hues 2, while also proposing bias reduction strategies.3,4

An Ecosystem Emerges

When it comes to conducting research on facial recognition technology, designing studies to test the technology’s accuracy, speaking out on facial recognition technology’s potentially devastating consequences for vulnerable communities, and pushing for policies that will help safeguard the public from these abuses, Black women have taken the lead. And this leadership has extended beyond the worlds of academia and research to also include advocacy, organizing, and thought leadership on facial recognition technology within the larger context of algorithmic bias.

The proliferation of its use means that facial recognition technology too often translates to facial surveillance technology, which could contribute to the marginalization of vulnerable populations.

An ecosystem of scientist- and scholar-led nonprofit organizations has emerged to fight bias in AI systems. Many of these nonprofits are led by women of color, especially Black women—the group most likely to go unseen, unrecognized, or mismatched by facial recognition technology, or to experience algorithmic bias in other forms. Joy Buolamwini, whose initial research and TED Talk brought facial recognition technology and its inequities to national attention in 2016, founded the Algorithmic Justice League (AJL). AJL combines “art and research to illuminate the social implications and harms of AI.” Buloamwini has also recently published a book on the subject, Unmasking AI: My Mission to Protect What Is Human in a World of Machines.

After being publicly ousted from Google in 2020, Timnit Gebru, a frequent collaborator and co-author with Buolamwini, started the Distributed AI Research Institute (DAIR), which creates “space for independent, community-rooted AI research.” AI for the People, founded and led by Mutale Nkonde, serves as an “advocate for policies that reduce the expression of algorithmic bias.” Another nonprofit—Women in AI Ethics—founded by Mia Dand works to “increase recognition, representation, and empowerment of women in AI ethics.”

Facial Recognition Technology and Discrimination

One of the most alarming aspects of facial recognition technology is how widespread it has become. The technologies are scanning our faces at retail stores, airports, and schools, often without our knowledge or consent. Troublingly, facial recognition technology has also been used to surveil crowds at public demonstrations and protests. The proliferation of its use means that facial recognition technology too often translates to facial surveillance technology, which could contribute to the marginalization of vulnerable populations.

Unfortunately, as the research suggests, the inaccuracies of facial recognition technology has led to discrimination in several areas of everyday life. A few of the areas where facial recognition technology is perpetuating discrimination are discussed below.

Law enforcement

Among a plethora of potential issues posed by facial recognition technology, law enforcement’s use of the technology is the most salient, because it is also the most potentially dangerous and deadly use case for the tech. Facial recognition technology has led to several false arrests. A Wired article details three such cases, all three Black men—Robert Williams, Michael Oliver, and Nijeer Parks—and how their unwarranted arrests affected their lives. Facial recognition technology also resulted in the highly publicized arrest of a Black woman on suspicion of carjacking while she was eight months pregnant, as detailed by the New York Times. In each case, Black people were arrested for crimes they didn’t commit because facial recognition AI is notoriously inaccurate for faces with darker skin tones.

Due to its inaccuracy, and because of public backlash, law enforcement’s use of facial recognition technology is banned in some cities; however, the technology is still being used by law enforcement agencies throughout the United States. According to the Brookings Institute, Clearview AI, one of the most widely used commercial providers of facial recognition technology, has “partnered with over 3,100 federal and local law enforcement agencies.”

The Right to Protest

Facial recognition technology has been used to target activists. Derrick Ingram was tracked down by police who tried to invade his New York City apartment after he attended a Warriors in the Garden protest and was accused of yelling into a police officer’s ear with a megaphone. Though the charges were later dropped, the violation of Derrick Ingram’s privacy is still alarming.

According to Amnesty International, “These surveillance activities raise major human rights concerns when there is evidence that Black people are already disproportionately criminalized and targeted by the police.”

For vulnerable communities—which have long histories of being criminalized, targeted, surveilled, overpoliced, and violated by law enforcement agencies as well as excessively penalized by the criminal justice system—facial recognition technology could effectively nullify the right to peacefully protest without threat of retaliation, a right protected by the Constitution’s First Amendment.

Education

Due to the unprecedented and tragic number of school shootings in the United States, schools have found themselves under enormous pressure to address issues of school safety and security. As Arianna Prothero points out in an article for EducationWeek, within this atmosphere of anxiety and despair over school violence, “high-tech solutions such as facial and weapons recognition technology…can be an alluring solution for school boards and superintendents looking to reassure parents that their school campuses are safe.” However, the article also argues that engaging with students is often the most direct path to detecting threats to school security rather than diverting staff time to managing technologically complex security systems.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Moreover, a study from the University of Michigan’s Ford School of Public Policy calls attention to other potential abuses of facial recognition technology within a school setting, pointing out that the tech can also be used to conduct contact tracing, and monitor school attendance and behavior in the classroom. Whether the potential benefits could outweigh the risks of facial recognition in schools is still a matter of debate. Many schools are still grappling with the decision to allow facial recognition technology onto their campus. In September 2023, however, the New York State Education Department became the first department of education in the country to ban the use of facial recognition technology because the technology’s utility and appropriateness within schools was found lacking.

While issues with facial recognition technology have resulted in false arrests, fueled tactics used to surveil and intimidate activists, and track people (including school children) without their knowledge or consent, there are also positive applications of the technology that have the potential to help rather than hinder marginalized communities. For instance, according to Michael Gentzel’s article “Biased Face Recognition Technology Used by Government: A Problem for Liberal Democracy,” facial recognition technology “can help physicians diagnose diseases and monitor patients in the healthcare setting, find missing and lost persons, and help law enforcement apprehend dangerous criminals.”

If facial recognition technology remains largely unchecked, its abuses, which have been most largely and deeply felt by Black Americans, is likely to be felt by a larger segment of the American public in the future.

However, with facial recognition technology’s stark inaccuracies when it comes to recognizing faces of color and women, the likelihood that the communities most affected by facial recognition technology’s harms will fully benefit from its redeeming use cases is negligible. And as Gentzel argues, the risks seem to greatly outnumber the benefits, especially for marginalized groups.

In her book Race After Technology, Ruha Benjamin discusses why understanding what she refers to as “anti-Black technologies” such as facial recognition technology is crucial for understanding the scope of injustice perpetuated by technology even when these technologies “do not necessarily limit their harm to those coded Black”:

The plight of Black people has consistently been a harbinger of wider processes—bankers using financial technologies to prey on Black homeowners, law enforcement using surveillance technologies to control Black neighborhoods, or politicians using legislative techniques to disenfranchise Black voters—which then get rolled out on an even wider scale.5

If facial recognition technology remains largely unchecked, its abuses, which have been most largely and deeply felt by Black Americans, is likely to be felt by a larger segment of the American public in the future.

Policy Implications

Like any technology, facial recognition technology is a tool that can be used for or against the public good. As long as people keep pushing for positive change, there is still hope for a future where facial recognition technology will benefit all members of society. Though experts in the field of AI ethics are leading the charge, there is also an important role for everyone else who is affected by facial recognition technology or concerned about its abuses.

Alondra Nelson is one of the voices calling for greater transparency and accountability in the use of AI while simultaneously creating AI governance frameworks that forge a path for more ethical, sustainable, and equitable uses of the technology. According to Nelson, in a Center for American Progress article, one of the glimmers of hope surrounding the use of AI is that it has sparked an “ongoing, rich public debate about the current and future use of artificial intelligence.”

Since facial recognition technology will impact our society at large, Nelson argues that “we all deserve a role in giving shape and setting terms of how it should not be used.” Buolamwini, in a 2021 New York Times podcast, echoed much of the same sentiment regarding the public’s right to be included in discussions about when, how, and if facial recognition technology should be used. In a nod to the ubiquity of the technology, she said, “If you have a face, you have a place in this conversation.”

Outside of nonprofits and other mission-driven organizations who exclusively focus on the detrimental effects of technology, Nelson also argues that AI policy has implications throughout the broader nonprofit, social movement, and advocacy landscape. She stated that “anyone engaged in advocacy in a movement—from women’s health care rights and civil rights and to climate crisis activism and labor activism—should see AI as a tool that may advance their work or frustrate it, and engage accordingly.”

But time isn’t on the side of advocates and activists concerned about the reach and deleterious outcomes associated with facial recognition technology. Though there has been a great deal of movement in government and the nonprofit sector to understand and redress its harms, tech companies big and small are continuing to aggressively market surveillance-focused facial recognition software to law enforcement agencies, school districts, and private businesses. Consequently, the technology is still being used in airports, in schools, in clinical settings, in stores, in apartment complexes, and elsewhere. Ironically, like the databases the technology draws from and feeds into, facial recognition technology itself has many faces.

Notes

1. Amazon released a statement refuting the ACLU study because, according to Amazon, the ACLU researchers used incorrect settings while conducting their test. The ACLU used the default 80 percent confidence level for its test, though Amazon recommends a confidence level of “99% for use cases where highly accurate face similarity matches are important.”

2. Ashraf Khalil, Soha Glal Ahmed, Asad Masood Khattak, Nabeel AI-Qirim, “Investigating Bias in Facial Analysis Systems: A Systematic Review,” IEEE Access 8 (June 2020): 130751–130761. 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3006051

3. Inioluwa Deborah Raji, Timnit Gebru, Margaret Mitchell, Joy Buolamwini, Joonseok Lee, and Emily Denton, “Saving face: Investigating the ethical concerns of facial recognition auditing.” Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society (February 2020): 145–151. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2001.00964

4. Singh, Richa, Puspita Majumdar, Surbhi Mittal, and Mayank Vatsa, “Anatomizing Bias in Facial Analysis,” Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 36, no. 11 (2022):12351–58. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v36i11.21500

5. Ruha Benjamin, Race After Technology (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2019), 32.