January 3, 2020; Associated Press

We face serious health risks when waste from mines, factories, power plants, or farms is not handled properly. In 1980, the problem was seen as serious enough to require government intervention, and the federal Superfund program of the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was established to “protect human health and the environment by managing the cleanup of the nation’s worst hazardous waste sites and responding to local and nationally significant environmental emergencies.” Alas, 40 years later, the backlog of seriously polluted sites is growing, not shrinking.

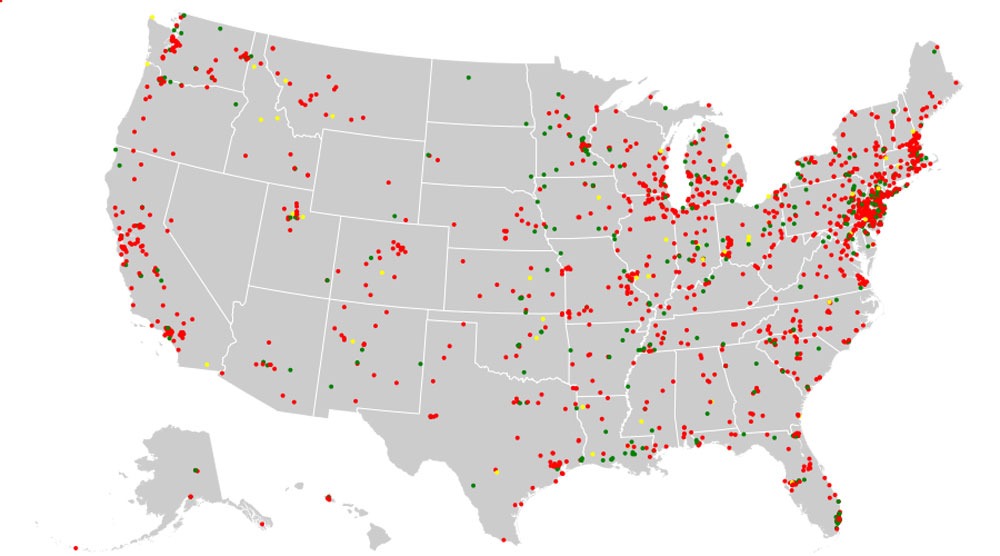

More than 1,300 places are on the EPA’s list of recognized Superfund sites, each posing some degree of danger. According to data recently released by the EPA, cleanup plans for 34 prioritized sites in 17 states and Puerto Rico are stalled for lack of funding. That compares with 12 sites in this category when President Obama left office and represents the greatest backlog the nation has seen in the past 15 years.

In putting forward its 2020 EPA budget, the Trump administration said it was committed to “strengthening [its] focus on protecting human health and the environment.” Then, it asked for a 31 percent reduction in funding for the agency. EPA administrator Andrew Wheeler underscored the Superfund’s importance in comments to Congress—“There may be no better example than our success in the Superfund program”—but has not asked for additional funding to get work going.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Elizabeth Southerland, who worked for 30 years at the EPA, including as director of science and technology in the water office, pointed to this contradiction when she told the Associated Press, “They’re misleading Congress and the public about the funds that are needed to really protect the public from exposure to the toxic chemicals. It’s detrimental.”

In a broader context, the growing number of unfunded Superfund projects is just part of a larger effort by the Trump administration to weaken regulations. According to a recent New York Times report, “more than 90 environmental rules and regulations were rolled back under Trump, [including] rules that were officially reversed and rollbacks still in progress.” In doing so, it has diminished the role of science and knowledge as the basis for policymaking. Syracuse University professor Peter Wilcoxen, who chairs an EPA work group examining the agency’s rollback of federal mileage standards, spoke to the Washington Post about concerns this approach raises. “You could end up establishing a regulation for huge sectors of the economy based on incorrect information.”

Some communities still fight to get recognition of the risks they face and get in line for federal cleanup. In North Carolina, for example, Buncombe County residents are advocating for help to remove toxins from the site of an industrial plant that closed 32 years ago.—Martin Levine