May 24, 2020; Tampa Bay Times and New York Times

“The State cannot condition voting on payment of an amount a person is genuinely unable to pay,” wrote federal judge Robert Hinkle this weekend in his 125-page decision in the case of Kelvin Leon Jones et al. v. Ron DeSantis et al.

But wait a minute! Why is this even a question? Didn’t the 24th Amendment to the US Constitution—you know, the one that says, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote in any primary or other election for President or Vice President, for electors for President or Vice President, or for Senator or Representative in Congress, shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any state by reason of failure to pay any poll tax or other tax”—resolve this issue over a half-century ago?

Well…it’s complicated.

The decision by Judge Hinkle rescues—mostly, we’ll get to the exceptions—Amendment 4 in Florida. Amendment 4, many NPQ readers will recall, stated that, except for those convicted of murder or sexual assault, “any disqualification from voting arising from a felony conviction shall terminate and voting rights shall be restored upon completion of all terms of sentence including parole or probation.”

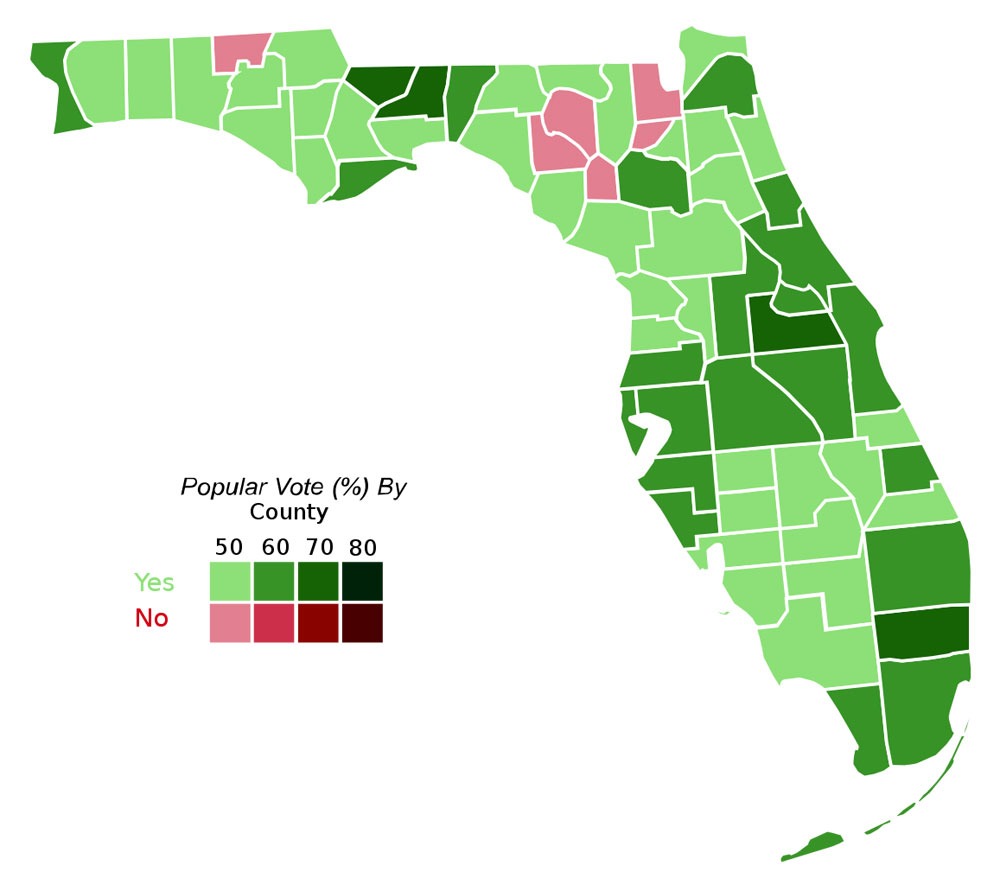

The measure was approved by Florida voters by an overwhelming 64.5 percent “yes” vote and promised to restore voting rights to as many as 1.4 million Floridians.

“Any” would seem to mean any. “But not so fast,” said the state legislature. Last June, Florida’s Republican legislature passed Senate Bill 7066, signed into law by Governor Ron DeSantis (R), which requires former prisoners to not only complete “all terms of sentence including parole or probation,” but to also pay any costs owed to the state, including fines, court fees, restitution, and accumulated interest. Notice that none of these words had appeared in the amendment that Florida voters overwhelmingly approved. To say the least, the Florida state government had taken a very liberal interpretation of the meaning of the phrase “all terms of sentence.”

Even better—from a voter suppression standpoint, that is—is that the amount owed by the former prisoner seeking to have his or her voting rights restored is often unknown. As Judge Hinkle wrote, “The State is on pace to complete its initial screening of the citizens by 2026, or perhaps later, and only then will have an initial opinion about which citizens must pay, and how much they must pay, to be allowed to vote.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Hinkle’s ruling does away with this nonsense. In particular, Hinkle rules that former prisoners cannot be denied the right to vote if they cannot afford to pay—and that it is presumed that a person is unable to pay if the person seeking voting rights restoration had an attorney provided for their criminal case because they couldn’t afford one on their own, or if their financial obligations had been converted to civil liens.

However, Hinkle’s order also allows that “the State can condition voting on payment of fines and restitution that a person is able to pay.”

Under Hinkle’s injunctive order, however, the state cannot wait until 2026. It will have 21 days after receiving a person registers to vote to challenge it, after which the state can no longer intervene.

Hinkle notes that, “In most cases, the Division (of Elections) will need to do nothing more on (legal financial obligations) than review the judgment to confirm there is no fine or restitution…in the remaining cases—the cases with a fine or restitution—the overwhelming majority of felons will be unable to pay.”

Carl Tobias, a law professor at the University of Richmond tells Lawrence Mower of the Tampa Bay Times that Hinkle’s ruling is “perhaps the most important ruling in the US now ahead of the November election.”

“This ruling means hundreds of thousands of Floridians will be able to rejoin the electorate and participate in upcoming elections,” adds Julie Ebenstein, senior staff attorney with the American Civil Liberty Union’s Voting Rights Project. “This is a tremendous victory for voting rights.”

Mower noHinkle’s grant of permanent injunction relief is expected to be appealed. However, the judge’s cautiously worded ruling may make a successful appeal by the state of Florida more difficult. As Patricia Mazzei observes in the New York Times, “Much of Sunday’s ruling is built on a previous ruling by the United States Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit in Atlanta, which would hear any appeal.”

A bigger challenge might be the clock. Mazzei points out that, “with an appeal likely—and legal and political steps beyond that uncertain—it’s too early to assume that people affected by the ruling will be able to register to vote in time for November—or how many will vote even if they do.”—Steve Dubb