August 15, 2018; Columbian (Vancouver, WA)

On the surface, a recent article by Patty Hastings in The Columbian about financial difficulties at The Arc of Southwest Washington (TASW), based in Vancouver, Washington (just north of Portland, Oregon), is a typical nonprofit tale. Margins are tight, difficult decisions about expenses and assets need to be made, and there are internal and external tensions and pressures of concern for the board, staff, volunteers, funders, and donors. Ultimately, of course, all of this directly impacts the beneficiaries of the Arc—namely, the individuals with intellectual disabilities who the nonprofit seeks to serve, as well as the communities in which they live.

The story also points to broader implications about infrastructure management that are applicable to the nonprofit community as a whole. By their very nature, physical assets like buildings and equipment deteriorate over time, and even with the best of governance and stewardship, accounting for their future maintenance costs is always a paper exercise, dependent upon many future variables. This represents a “double whammy” scenario as described by Clara Miller: Not only do they incur increasing costs, but funders and donors are not easily attracted to investments in repairs and renovations.

Understanding the workings of any nonprofit organization should never be reduced to an analysis of financial statements, but certainly TASW is facing challenges 1-2 as identified by Hager and Searing in “Ten Ways to Kill Your Nonprofit”: 1) overwhelm it with liabilities and 2) operate in the red. While caution is always advised with respect to reacting to year-to-year fluctuations in revenues and expenses, the potential albatross of deteriorating physical assets and ongoing deficits—without apparent opportunities to address them—cannot continue indefinitely.

Today’s plans for the future of nonprofit infrastructure are not only impacted by obvious financial issues like changes in funding and/or policy, they are also influenced by changing mission-oriented perspectives, with pressures that can come from both internal and external stakeholders.

The current challenges and opportunities facing The Arc of Southwest Washington in supporting people with intellectual disabilities (such as Down syndrome and autism) offer a window into similar choices that have been faced or are in active consideration by countless nonprofits that have undergone a similar journey in balancing past legacies with future needs and opportunities.

An outgrowth of disparate pre-war movements, led primarily by parent groups seeking a better life for people with intellectual disabilities in the ’30s and ’40s, The Arc was founded in 1950 and now includes some 700 local and state chapters. In the early days of the movement, supporters were driven by a desire to improve the existing institutions that were home to their loved ones, while at the same time questions were already being asked about whether or not a life lived in institutional settings was appropriate or necessary for the population.

Some 65 years later, the size of the institutional settings has changed, but the debate and the implications pertaining to both finances and intended outcomes are similar. John Weber, the interim leader at TASW cites both cost reduction and shifting priorities in explaining the decision to sell off the organization’s massive 8,000-square-foot headquarters, which in addition to office space, has served a variety of functions, including a sorting depot for donated items, thrift store operations, and other activities that fit into a the general category of a “warehouse facility.”

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

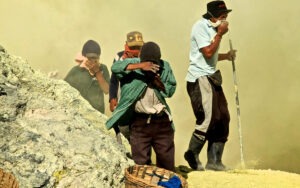

The symbolism of “warehousing” is a touchpoint in the intellectual disability community. This type of programmatic social services infrastructure is increasingly seen as a vestige of the past, when agencies sought to help people with disabilities find their place by creating parallel social and economic environments that are located within—but not necessarily as part of—authentic communities. Carol Blessing et al. described the problems of “segregated infrastructure” in their 2012 article on “Vocational Rehabilitation, Inclusion, and Social Integration”:

The deinstitutionalization movement of the 1960s was in response to the significant human rights violations experienced by people in institutions…Unfortunately, the movement of people out of large institutions…without much planning for meaningful community-based alternatives [resulted in] a proliferation of smaller but nevertheless segregated programs and services.

The pressure to continue moving away from a medical model approach to a social model (focused on more inclusive outcomes) is very much a part of the current tensions at TASW, and according to Weber, “That’s the direction we’ve been heading for many years now.”

The State of Washington Developmental Disabilities Administration hosts one of the nation’s leading-edge conferences on these transitions, the Community Summit. (I had the honor of attending and speaking there in 2014. Although just four years ago, my shared plenary with Julie Kingstone on the “Journey to Social Inclusion” represented to some degree the musings of radical outsiders. The vibe of that time was “Sounds great, but if we don’t have these programs, we don’t really believe we’ll have anything at all.”) Looking at the offerings from the 2018 Community Summit, there is little doubt that a dramatic shift has taken place in just four short years. The agenda represents a relentless variety of perspectives—both theoretical and practical—on the why and how of moving to community-based and person-centered outcomes. There isn’t a session to be found that explains “how to set up a facility for group programs.”

We see instead The Arc of Rensselaer County (NY state) sharing their journey from group-based to individualized supports, or a seminar by legendary advocate Ari Ne’eman about “Employment First” the growing movement to eliminate the work-like programs represented by the historical uses of the very type of facility that TASW is currently offloading.

It’s a model that still permeates many states across the country, but whether it is being removed via legislation or economic collapse, there’s little chance that it won’t soon exist only as a historical footnote on the continuing path to inclusion.

The ownership of physical assets that intentionally or unintentionally reinforce segregation is perhaps unique to particular segments of the nonprofit sector (people with intellectual disabilities, mental health facilities, and services for seniors to name a few) but it extends more broadly to questions about nonprofit purpose: Do they exist to “run programs” or to change society for the better?

The extent to which TASW is responding to financial necessity versus being driven by a mission-oriented imperative is not known, but we look forward to following this evolving situation. If new leadership can effectively navigate these challenges, it could be a win-win with better outcomes at lesser expense—the holy grail of nonprofit management!—Keenan Wellar