On January 6th, five people, including a Capitol police officer, were killed. Property that belonged to all the people of this nation was damaged and destroyed. Our sense of democracy and the rule of law was shaken, and many want to hold Donald Trump accountable for inciting those who carried out this insurrection. But the First Amendment, as interpreted by the US Supreme Court in Brandenburg v. Ohio, sets the bar for finding a defendant guilty of “incitement” very high.

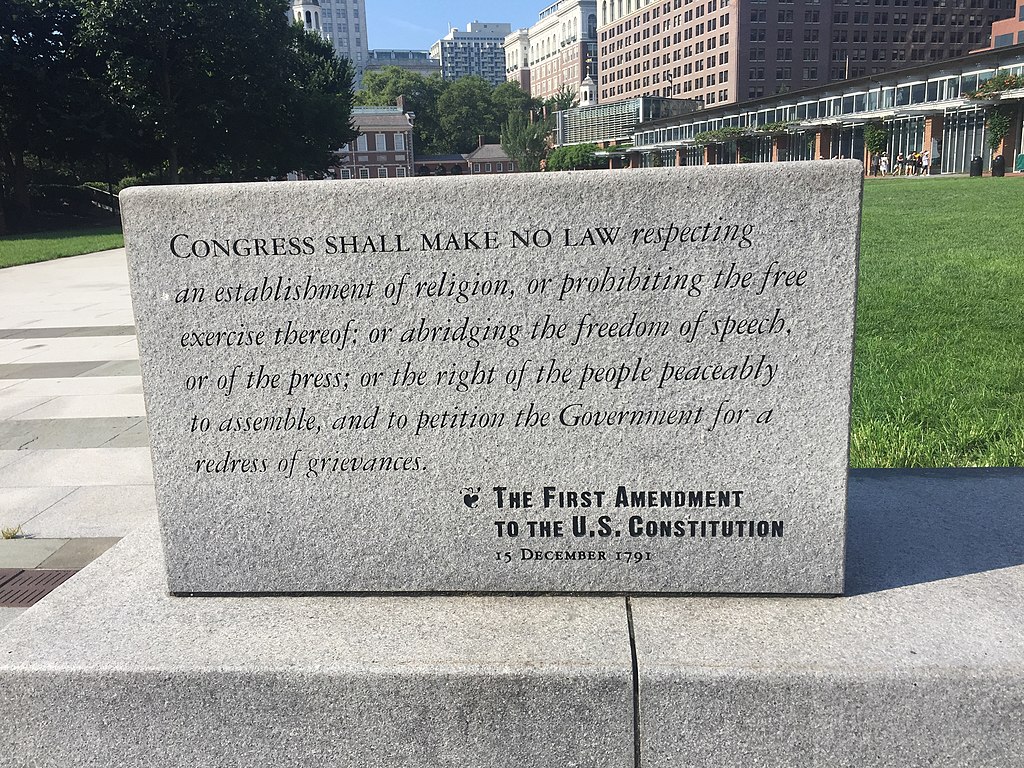

First Amendment protections of freedom of speech are not absolute. Our freedom of speech falls into two categories: protected speech and unprotected speech. Most speech is protected; examples of unprotected speech include incitement to illegal activity and/or imminent violence, defamation, obscenity, child pornography, threats and intimidation, and false advertising.

Trump’s tweets and his charge to the “Stop the Steal” rally protesters on January 6 seem to fit a few unprotected speech categories. He told his followers, “We will not take it anymore” and “If you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore.” The question, however, of whether Trump can be successfully prosecuted in court for incitement is not clear, based on past Supreme Court cases.

“The question of when an individual can be punished [in a manner] consistent with the First Amendment for inciting others to engage in unlawful conduct has long haunted the Supreme Court,” says Geoffrey Stone, Edward H. Levi Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of Chicago and coeditor with Columbia University president Lee Bollinger of a forthcoming volume on National Security, Leaks and Freedom of the Press: The Pentagon Papers 50 Years On.

Stone explains that the Court first addressed this question during World War I to uphold convictions of draft resisters or individuals who criticized the war. The “bad tendency” test was used to crush “disloyalty” and helped convict people under the Espionage Act of 1917 for merely publishing treatises against the war (as in Shaffer v. United States, 1919). In a later case that same year, Schenck v. United States, judges abandoned the “bad tendency” test for “clear and present danger” to distinguish between free speech and language intended to spur action against the government.

“Over the next 50 years the Court wrestled with this issue in a range of circumstances, including during the Communist era, but ultimately embraced a highly speech-protective approach in Brandenburg v. Ohio in 1969, in which the Court held that a person cannot constitutionally be punished for speech because it might lead others to act unlawfully unless the speaker had specific intent to bring about this result and the harm was likely, imminent, and grave. Applying this standard, the Court has not upheld any conviction for causing others to commit crimes through speech since,” says Stone.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Again, the issue of specific intent becomes key. The Brandenburg case involved a Ku Klux Klan member, Clarence Brandenburg, who was convicted for making anti-Semitic and anti-Black statements and called for “revengeance” against the government actions that wanted to “suppress the white, Caucasian race.” He was sentenced to 10 years in prison under Ohio’s Criminal Syndicalism law for inciting “imminent lawless action.” His case was unanimously overturned by the Supreme Court in 1969.

Lee Rowland, a senior staff attorney with ACLU’s Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project explains for TalksOnLaw that the Brandenburg decision could be seen as an all-white male court favoring a white supremacist. But in NAACP vs. Claiborne Hardware in 1982, the Court ruled in favor of civil rights activist Charles Evers, who at a rally encouraged people to boycott “racist, white-only businesses” and threatened to break the necks of people who shopped in such places. The Court’s decision also upheld the right to boycott products or companies for political purposes as a form of free speech.

“One question left unclear after Brandenburg, and still unresolved, is whether the speaker must also have expressly advocated unlawful conduct (in addition to having specific intent to cause unlawful conduct and that the harm was likely, imminent, and grave),” says Stone.

Stone points out that social media, as a form of speech, is no different from a First Amendment perspective, so one would need to look into Trump’s Twitter posts before the January 6 rally. Yet, the core issue here may not be freedom of speech but rather one of accountability.

We are witnessing an ever-growing number of right-wing groups that are willing to use violence to enforce their belief in white supremacy. Those who hold public office hold greater authority and responsibility than those who do not. They need to be held accountable for what they say and do in ways others may not have to be. On January 6th, we witnessed an attempted coup that could have taken down our democratic process. It did not, but lessons need to be learned.

Reining in this violence and preserving free speech rights are both important goals. The courts have tread lightly when it comes to free speech, but Trump’s aggressive undermining of democracy and condoning violence may well have created a need to devise more stringent standards for public officials. With Trump now impeached a second time and a trial looming in the US Senate, Congress may be able to do what the judicial system cannot and consider the broader scope of Trump’s speech, tweets, actions, and nonactions. Based solely on the Brandenburg precedent, however, it might be easier to prosecute Trump for tax evasion than incitement.—Carole Levine