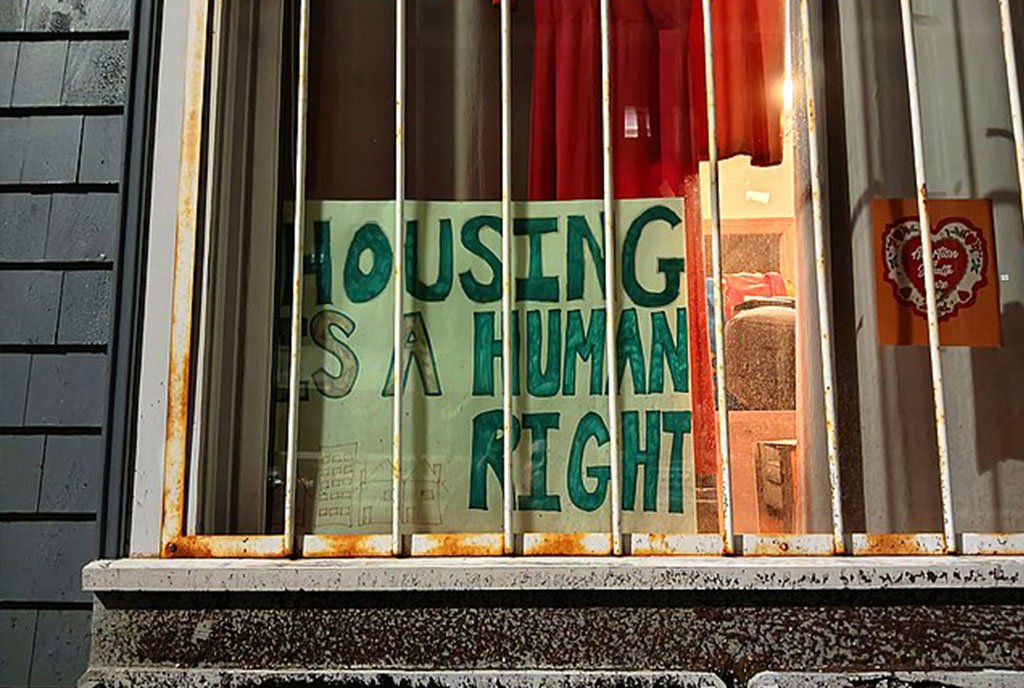

When you see the phrase “housing policy,” what do you imagine? Many people may imagine large, multi-unit buildings and arguments over zoning or code enforcement or the definition of affordability. But what about the people in those buildings?

Tenant organizing, and tenant unions specifically, are an attempt to ensure that tenants—44 million households nationwide—are not merely consumers of housing policy but authors of their own stories.

Driving the growth of tenant unions is a simple truth: Traditional solutions to the housing crisis have not worked.

Tenant unions are not new, but the current wave of tenant organizing reflects today’s economic conditions, which make it increasingly difficult in cities across the country for anyone but the wealthiest to comfortably afford a place to live. In this environment, a new generation of tenant organizers has emerged—people who understand that the single best place to connect with community members is at their door, talking about the single biggest economic issue facing their family.

Shifts We’ve Seen

Driving the growth of tenant unions is a simple truth: Traditional solutions to the housing crisis have not worked. You can build more houses, sure. But relying on the market to solve the affordability crisis ignores the structural problems and power dynamics baked into our housing system.

Following the Great Recession, corporations and private equity firms aggressively purchased multifamily rental housing, single-family homes, and manufactured housing communities. In early 2024, as much as 30 percent of new single-family home sales were to investor groups. The fundamental profit-seeking goals of these companies have contributed to increasing rents, as well as instability and housing insecurity. And it’s only getting worse. By some estimates, private equity firms will control 40 percent of the single-family rental market by 2030.

On the organizing side, the move to tenant organizing marks an evolution from two decades of philanthropy-funded efforts that largely focused on big cities with Democratic-leaning politics in which policy campaigns aimed for some combination of anti-displacement and affordable housing. As preemption at the state level wiped out all but a handful of the policy achievements from that era, the demands from organized tenants grew more ambitious.

As a result, the organizing approach to who, how, and for what purpose organized tenants acted shifted dramatically. And during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the “Cancel Rent” moment and movement crystallized a massive constituency of tenants.

What Is a Tenant Union?

The definition of a tenant union is not etched in stone, but there are a handful of criteria that help describe this organizing structure:

- Tenant unions are organizing tenants in their identity as tenants.

- Tenant unions are often focused on a specific set of tenants, either living in one building or in a set of properties owned by a common landlord. This could mean a slumlord of one building, or a private equity firm that owns multiple buildings in one city, or even Project-Based Section 8 buildings, under the control of HUD (the US Department of Housing and Urban Development).

- A tenant union can be neighborhood- or citywide, across multiple landlords. Organizing across geographies, even states, to form a larger, potentially even more powerful, tenant union can position it to bargain with a corporate landlord with multiple properties and/or effect citywide policy change.

- In all these iterations, organized tenants share a common and specific economic relationship of paying rent to a certain landlord, as well as an ideological and political commitment to a set of values and beliefs, including that everyone deserves access to safe, affordable housing.

Tenant unions often have room for allies, but decision-making about campaign strategy and tactics lives with the tenant leadership. Thus, tenant unions’ member base of people identifying as tenants and their internal democratic structure distinguishes them from other housing justice groups.

A policy victory should both improve the material conditions of tenants and expand their ability and opportunity to organize more tenants.

What Winning Means

Tenant organizing has won unprecedented advances in recent years at the federal, state, and local levels, and these victories helped catapult tenants’ rights and rent stabilization into the national debate.

During the Biden administration, pressure from a strong tenant-led federal campaign resulted in a White House blueprint for tenant protections. While the new administration may attempt to roll back some of this progress, it is important to recognize the tenant power that propelled these wins and the long-term plan to protect what we have and create what we need.

For instance, the quasi-autonomous government-sponsored enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac established a set of multifamily tenant protections for properties they finance. Last year, too, HUD put a 10 percent rent increase cap into effect that covers all properties backed by Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC).

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Meanwhile, at the state and local levels, tenants are leading dozens of campaigns, including the following:

- In Montana, Bozeman Tenants United, a citywide tenant union with over 300 members, is building a multiracial, intergenerational movement of tenants to win safe, dignified, and truly affordable housing for all. In late 2023, the union won a campaign banning the use of homes for short-term rentals, ensuring more housing stock remained available to residents. They engaged tenants and community members in town halls, rallies, and organizing an overwhelming amount of public testimony regarding the impacts of the housing crisis on community members.

- In North Carolina, the North Carolina Tenants Union (NCTU) formed last year as the statewide union of local tenant unions across the state. NCTU supports its member unions in waging a range of tenant-led local campaigns aimed at strengthening tenants’ rights, stopping displacement, winning repairs, and combating rent increases. After Hurricane Helene, NCTU organized to cancel rent and stop all evictions for thousands of public housing tenants in Asheville.

- Colorado Homes for All, a statewide housing justice coalition that includes many tenant-led organizations as members, won a multiyear fight to help pass a good cause eviction law in 2024 to protect tenants from unjust evictions. COHFA has numerous multisector, multi-issue member organizations that share a common concern around housing and tenant rights. The coalition is continuing to work on rent stabilization efforts in Colorado.

These stories do not end with the policy win. The lesson is that tenants organized and built enough power to win, not simply to pass policies or legislation, but to continuously push to implement, enforce, and improve upon them—and to design the next campaign and fight the next fight.

A policy victory should both improve the material conditions of tenants and expand their ability and opportunity to organize more tenants and shift the broader narrative around ownership, land, and capital. These intermediate wins move society closer to the larger goal of challenging the central premise that one person’s home is another person’s investment vehicle.

Leveraging Tenants’ Economic Power

Organized tenants have a specific form of economic leverage over landlords and building owners: withholding their rent. Coordinated rent strikes across multiple properties and landlords can escalate concerns.

In October 2024, for example, tenants in Kansas City, MO, launched a rent strike in two buildings with demands of their corporate landlord, Sentinel, and the federal government, which subsidizes it. The tactic of directly challenging landlords for economic control, rather than exclusively relying upon legislative campaigns and public goodwill, is a critical piece of changing existing power dynamics in the housing market.

There is no path to economic power, justice, or security that does not contest for control with organized capital.

Understanding tenant organizing means reframing the traditional thinking about organizing campaigns as exclusively about winning legislative or administrative policy changes, or engaging in electoral spaces, or running corporate campaigns against egregious actors. Instead, the various forms of campaigning are all downstream from a larger theory of change about tenant power, and distinct from most other forms of campaigning is the economic leverage that organized tenants can directly apply.

Role of Philanthropy

Historically, philanthropy has taken a mostly supply-side approach to addressing the housing crisis and has failed to resource the people and communities organizing for change. Because large foundations often struggle to reach nascent, emerging groups and are reticent to fund tenant organizing at scale, intermediaries play a critical role in supporting the tenant movement.

Funds like HouseUS, where I work, and the Fund for an Inclusive California have been moving money to tenant organizing and providing valuable forms of non-grantmaking support for several years.

It is past time for philanthropy to step up. The are options: fund directly, fund through intermediaries, or both.

When it comes to housing justice, the data is clear. More housing alone will not solve the growing crisis of housing affordability.

Simply put: There is no path to economic power, justice, or security that does not contest for control with organized capital—and that means challenging the hold of the investor class over land, homes, and property. It is time for housing justice nonprofits and philanthropy to seriously examine what will be required for them to work in solidarity with organized tenant unions so that together, we can build a housing system that guarantees a safe, permanently affordable home for all.