The Giving USA report is published annually by Giving USA Foundation, a public service initiative of The Giving Institute. It is researched and written by the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy. The 2017 report, which covers this country’s charitable giving in the 2016 election year, provides extraordinarily promising news for nonprofits that see their givers as more than just automatic tellers.

Readers will remember the surges in giving that extended from last year into this one:

Planned Parenthood received nearly 80,000 donations just three days after the election. The ACLU got more than $24 million in online donations in a single weekend, and Meals on Wheels experienced a surge in donations after reports of federal budget cuts.

These small snapshots promised some blips in the giving landscape for last year, but many were uncertain whether the phenomenon was all that significant and what it would do to the giving landscape in general.

The numbers in this report begin to tell the story, though, and the first important finding is that even with all the dollars pouring into the coffers of groups like the ACLU and Planned Parenthood after the election, other kinds of organizations did not appear to suffer for it. Giving in 2016 was very healthy, hitting an all-time high of $390.05 billion. The second is that even amid great political uncertainty, and probably even because of it, people without enormous wealth gave in larger numbers than they have in the recent past.

The first finding puts to bed the spate of alarmist articles suggesting that the outpouring of donations to “resistance-oriented” groups would reduce the donations to other kinds of advocacy or to service-oriented groups. In fact, the report projects that all nine categories of recipient organizations saw an increase in 2016, a very rare phenomenon. Those increases were not inconsequential, ranging from a high of a 7.2 percent increase in giving to environment and animal organizations (for a total of $11.05 billion) to a low of a 3 percent increase in giving to religion. (Giving to individuals actually decreased by 2.5 percent.)

Patrick M. Rooney, Ph.D., associate dean for academic affairs and research at the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, points out that the highest increases among recipient groups were in the environment, health, international affairs, and the arts. All of these categories were front and center in public and political discourse toward the end of 2016 as areas that might be targeted for policy changes and defunding by the new administration.

“In 2016, we saw something of a democratization of philanthropy,” said Rooney. “The strong growth in individual giving may be less attributable to the largest of the large gifts, which were not as robust as we have seen in some prior years, suggesting that more of that growth in 2016 may have come from giving by donors among the general population compared to recent years.”

In an interview with NPQ, Rooney also explained that donations like those that flowed to resistance-associated groups after the election would probably act much like disaster-related contributions, in that they would not displace givers’ contributions but generally be over and above.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

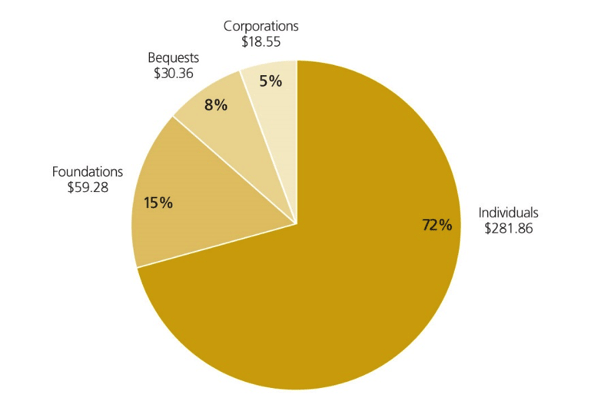

This brings us to the second important point, which is that individual gifts of the non-mega-scale variety appeared to display a serious uptick this year. The research found that the overall 2.7 percent increase in charitable giving from all sources was primarily driven by a four percent increase in individual giving. Four percent may not seem like a lot, but since individual giving composes 72 percent of the giving pie, or more than $281 billion, four percent represents a good deal of money.

In addition, as Rooney reports, the number of very large gifts in that individual category was depressed, meaning that a significant portion of the increase had been in small to mid-size gifts. The fact that bequests also declined means that larger gifts were not a part of the growth this year. All of that, as Rooney posits, implies good news in the civic health space, as reflected in numbers of donations.

All of this should come as little surprise to nonprofits, since we already knew that volunteering and giving are relatively closely linked behaviors. Thus, the massive number of people who volunteered to show up for protests on climate policy, immigration, science, and women’s rights over the past six or seven months should have been something of a predictor of what we could expect in giving trends. That makes this an exciting moment for fundraisers and organizers. As we reported in April:

The Albuquerque Journal reports that local environmentalists “are calling, emailing, showing up at meetings, donating money and offering to lobby legislators in support of measures aimed at promoting renewable energy in place of burning fossil fuels.” This comes in response to Trump’s promises to “end the war on coal” by rolling back measures aimed at curbing greenhouse gas emissions, and lifting a moratorium on the sale of coal-mining leases on federal lands.

[…]

Environment New Mexico, a research and advocacy group lobbying for greater renewable energy requirements, has also experienced increases in support since the November election. People email asking how they can help, current donors to the cause are increasing their contributions, and new donations are flowing in. The group reports that people offer to write letters or make phone calls to legislators, and even go to the state Capitol.

Imagine these scenarios reenacted all over the country, and you get a sense of the potential of this moment.

So, in summary, the political uncertainty of the past year did not restrain but rather motivated giving. There were fewer mega-gifts and many more small and mid-sized gifts. This may well have been the result of increased civic activism in general, but it does not appear to have reduced the giving to other types of groups—at least, not that we can see in these numbers.

What this means in terms of action steps is that the small to mid-size supporter is the big story right now. Once you have attracted those donors, your job is to engage and keep them as active and respected community members. It may be time to concentrate on making the most of this period of multi-faceted activism and our very rich landscape of mobilizable human and cash capital.