March 29, 2018; The Crimson

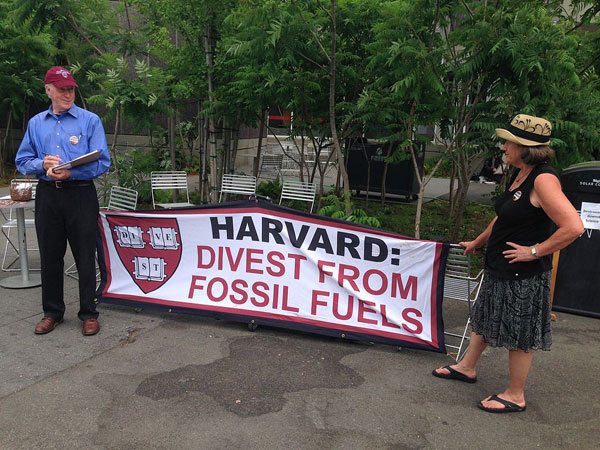

Kat Taylor, a member of Harvard University’s Board of Overseers, has written an op-ed publicly asking university president-elect Lawrence Bacow and the Harvard Corporation to “adopt ethical investment principles,” which includes, at a minimum, asking the Harvard Management Corporation to divest the university’s endowment from fossil fuels.

HMC is a separate body from the University and the Overseers, and its “singular mission is to help ensure Harvard University has the financial resources to confidently maintain and expand its preeminence in teaching, learning, and research for future generations.”

The issue of Harvard’s non-divestment has been in the public eye for years. Current university president Drew Gilpin Faust stated in a public letter in 2013 that the university would not divest. A student group called the Divest Project sued the university in 2014, claiming that as the Harvard Corporation is “a nonprofit corporation organized for educational purposes,” its “investment in fossil fuel companies is a breach of its fiduciary and charitable duties as a public charity and nonprofit corporation.”

Taylor has been in office since 2012, and her term is up in May, but it doesn’t seem this is a lame-duck advocacy campaign. University spokesperson Melodie L. Jackson said, “Kat Taylor has long made her support for divestment known to colleagues on the governing boards.” Taylor herself claims that “I have tried everything else—diplomatically in the background with other Overseers and outspokenly but behind closed doors in plenary. But this is too important for me to remain silent.”

Taylor is the wife of Tom Steyer, a philanthropist who encourages millennial activism and political engagement, as covered by NPQ. She stepped away from the legalese of Divest Project’s case and claimed that divestment “would not only take steps to address the existential crisis of our time, but it would allow the University to lead its peers.” (As a number of schools, including Columbia, Georgetown, and the University of California, have already divested, the leadership spot is questionable, but Taylor is correct that divested schools are in the vast minority.)

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

President Faust argued that though “climate change represents one of the world’s most consequential challenges,” the university ought to “be very wary of steps intended to instrumentalize our endowment in ways that would appear to position the University as a political actor rather than an academic institution.” This only applies to fossil fuels, however, if one views climate change as a purely political problem, which it is not; it is indeed more politically charged than it ought to be, but it is at heart a scientific and sociological issue, aside from the dubious claim by elites that their actions are apolitical. Faust also sidestepped the argument of moral leadership by claiming that the shares would simply find other buyers, but as nonprofit leaders know, the argument that someone would do it doesn’t make it the right choice for your organization.

Harvard has participated in prior divestment campaigns, including from tobacco and the apartheid-led South African government, albeit somewhat late in the latter case. What makes fossil fuels different?

As Rick Cohen pointed out in 2014, “The power of divestment campaigns is that they can bring multinational corporations and government to their knees not financially, but politically.” Divestment campaigns are as much about taking a public stand as they are about making it financially difficult for bad actors to operate. Former US Representative Barney Frank (D-MA) said, “Changing out of fossil fuels is important, but it doesn’t have the same moral problem” as apartheid. That we do not understand climate change as a moral problem is an issue of public perception that institutions like Harvard, which has enormous sway over public opinion and the messaging power of thousands of world-renowned experts, has the power to change.

This is one of the hinges on which Taylor’s argument swings. She wrote, “Especially because it is so influential, Harvard should give moral direction to how HMC manages the endowment.” The other hinge is practical: As Taylor points out, fossil fuel investments aren’t doing so well. HMC actually paused its investments in fossil fuels last year because the university was losing money. Taylor asked HMC to think more long-term, saying, “Clearly, the riskiest thing to do is nothing.”

Harvard’s mission is to “educate the citizens and citizen-leaders for our society.” Though its purpose is education, its position in the world gives it greater responsibility for moral leadership—responsibility that it has acknowledged and demonstrated on more than one occasion. If the university waits too much longer to act on what its stakeholders know is right, it risks being led rather than leading.—Erin Rubin