August 18, 2015; Washington Post and NPR

NPQ would like to invite comments and articles in response to this newswire.

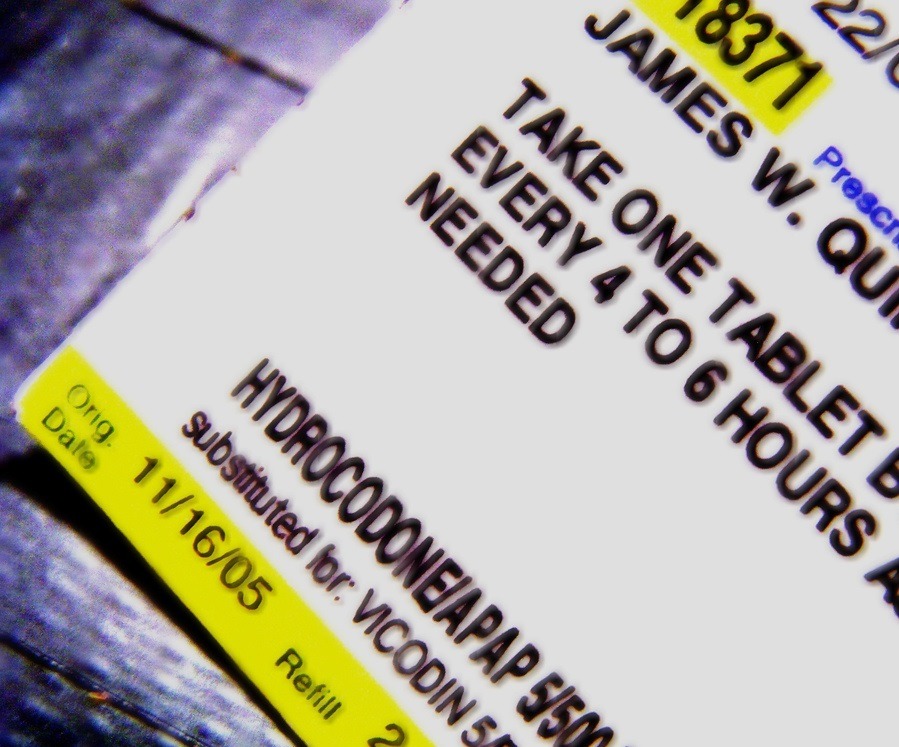

With increases in addiction to opiates approaching epidemic proportions, governments are scrambling to address the issue with innovative programs, funding, and policy shifts. However, it takes time before these efforts make things easier for the nonprofits on the ground, and responses vary from place to place.

Seeking help for heroin addiction in the Chicagoland area is no easy feat, even though Chicago is one of the hardest-hit cities in the country. Chicago is the leader in heroin-related emergency room visits. That may be due in part to delays; according to Kate Mahoney of PEER Services, located in Chicago’s northern suburbs, many patients have been waiting as long as five months for treatment services—and as the Illinois budget crisis continues, the wait is growing . The problem is exacerbated since Illinois is one of the few states that has bucked the national trend and cut funding for treatment.

A new study by the Illinois Consortium on Drug Policy at Chicago’s Roosevelt University found that 35 percent of individuals admitted to Illinois-funded substance abuse treatment programs are there due to heroin addiction, more than twice the national average. The Consortium is celebrating its tenth anniversary developing policy and legislative analysis. Its projects explore and educate policymakers on the connections between substance abuse, mental health, and disadvantaged populations. The organization’s vision is to advocate for a new outlook seeing illegal drug abuse as a public health problem rather than a criminal justice issue.

One piece of legislation the Consortium is advocating for is the Heroin Crisis Act. Once adopted, heroin addiction medications and treatment would be covered by the state’s Medicaid program. It recently passed the Illinois legislature with bipartisan support and is languishing on Gov. Bruce Rauner’s desk.

In Manchester, New Hampshire’s largest city with a population of 110,000, the problem is excruciatingly acute. As reported in the Daily Beast, the number of people there making use of state-funded treatment programs rose by 90 percent over the past ten years for heroin and an astounding 500 percent for prescription opiate abuse.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

“We have in New Hampshire some of the highest per capita rates of addiction in the United States,” Tym Rourke, chairman of the New Hampshire governor’s commission on drug abuse, told the Beast. “So we are very, very much at ground zero for addiction. […] Right now, we are having an overdose death every day.” Since New Hampshire is a stop on all the early campaign trails, this issue is one that has garnered the attention of presidential candidates.

In Gloucester, Massachusetts, however, the chief of police is providing amnesty for men and women suffering from addiction if they come into the police station so they can be helped. (Since the program started, 109 people have traveled to the police station, some from as far away as California. Eighty percent have yet to celebrate their 30th birthday.) Three towns in Massachusetts and two in Illinois are planning to start similar programs, following Gloucester’s lead. The White House has taken note as well and added $2.5 million to combat the epidemic in New England, Appalachia, and East Coast cities.

“The war on drugs is over,” Gloucester Police Chief Leonard Campanello said recently. “And we lost. There is no way we can arrest our way out of this. We’ve been trying that for 50 years. We’ve been fighting it for 50 years, and the only thing that has happened is heroin has become cheaper and more people are dying.”

The police department is working with a local CVS to fund supplies of Narcan, a nasal medication that can reverse overdoses. For individuals without insurance, doses of the prescription drug can cost $140. Chief Campanello persuaded the drugstore to lower the price to $20; now, the police department provides it for free, paying for it using funds seized from drug dealers during investigations.

Besides working with existing nonprofits in this field, the Police Assisted Addiction and Recovery Initiative, a new nonprofit group of private citizens, business leaders, law enforcement officials and others has been formed to help spread the Gloucester model. Without throwing cold water on the basic concept, figuring out how to make it all work on the ground will take networks and a resourced treatment community as well as research.

In the meantime, how is the existing nonprofit treatment network faring? What headway might be made while attention is focused on the problem? Finally, are for-profit treatment centers viewing this as a business opportunity? We’d love to get your observations.—Gayle Nelson and Ruth McCambridge