March 4, 2019; New Yorker and The Intercept

Advances in technology and the falling costs of clean energy make the Green New Deal’s goal of transforming the US economy to zero emissions by mid-century “eminently achievable,” writes John Cassidy in the New Yorker.

“Last month’s rollout of the Green New Deal,” explains Cassidy, “has sparked a good deal of controversy” for its aggressive carbon reduction targets. Still, often the controversy, as Kate Aronoff points out in the Intercept, stems from fossil-fuel firm opposition.

Aronoff interviewed Derek Seidman, author of a report titled the Anti-Green New Deal Coalition, published last month by the Public Accountability Institute. Seidman notes that the Green New Deal approach “is in tension with their economic and policy ideology, their donor bases, or the gradualist, incrementalist ways” by which US politics has been conducted.

As Seidman explains, “The fossil-fuel industry possesses immense resources and power that it will use to try to destroy the Green New Deal. The top 25 oil and gas companies alone generated $2.2 trillion in sales and $73 billion in profit in 2017. Fossil-fuel-tied industries spent nearly $2 billion lobbying in the US from 2000 to 2016—and that was just around climate legislation. Since 2012, it has thrown at least $333.5 million into federal elections alone.”

One sign of the fossil fuel industry’s pervasive influence: Joe Crowley, the liberal, 10-term Democratic congressman who Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez defeated last year, now works for a law firm that counts “major corporate powerhouses from the defense, private prison, and fossil fuel industry” among its clients.

Still, if the political obstacles can be overcome, the technological hurdles are relatively minor by comparison.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

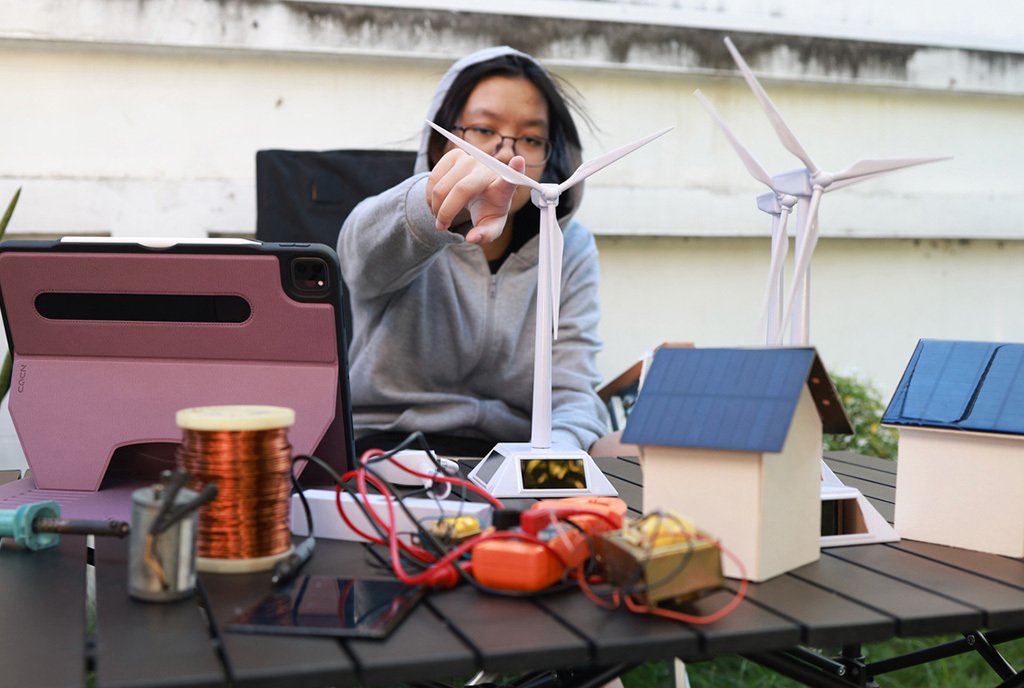

“Right now, we have about 90 percent or 95 percent of the technology we need,” Mark Jacobson, an engineering professor at Stanford, tells Cassidy. In a series of papers, Jacobson and his colleagues have laid out “roadmaps” to a zero-emissions economy. As Cassidy explains, “Just as in the Democrats’ Green New Deal, the central element of these roadmaps (and others) is converting the electric grid to clean energy by shutting down power stations that rely on fossil fuels and making some very large investments in wind, solar, hydroelectric, and geothermal facilities.”

One development that has helped in recent years, notes Cassidy, is a “steep fall in the cost of generating electricity from renewable sources.” Gains in efficiency with wind power have been particularly impressive. Costs have also fallen sharply in the solar-power industry. As Robert Pollin, co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts, points out, a decade ago “electricity generated from sunlight cost about twice as much as electricity generated from coal; now, the costs are roughly equal.”

Some communities are already shifting. For instance, the state of Iowa now generates more than 35 percent of its electricity from wind, yet the cost of electricity is a low 8.73 cents per kilowatt-hour, compared to a national average of 10.48 cents.

Still, as Jonathan Koomey, a special adviser to the chief scientist at the Rocky Mountain Institute, notes, “So far, all the tweaking around the edges hasn’t reduced carbon emissions nearly enough. You need to start shutting down high-carbon infrastructure on a schedule, and you need to stop building new carbon infrastructure. Ultimately, there is no other way.”

Of course, as Cassidy points out, “Even if we did succeed in creating an electricity grid entirely powered by renewable energy, getting to zero carbon emissions for the over-all economy would involve overcoming some tough problems, such as finding practical ways to store large amounts of energy for longer periods of time, and weaning long-distance air travel and commercial shipping from the fossil fuels on which they now rely.” Here too, however. are technological advancements that could make achieving Net Zero emissions far more feasible than it used to be. For example, Mara Prentiss, a Harvard physics professor, emphasizes the possibilities of low-carbon biofuels and synthetic fuels.

According to Jacobson, his plan to convert the US to clean energy would cost between 10 trillion and 15 trillion dollars. If the plan was enacted over 30 years, that would come out to as much as 500 billion dollars a year, or about 2.5 percent of current gross domestic product (GDP). As Cassidy points out, however, even at 2.5 percent of GDP, that is less than half of the annual defense budget.—Steve Dubb