The number of recorded disasters has increased fivefold over the last 50 years, according to the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). To reframe natural disasters as less “natural” and more the result of inequitable human development, a strategy balancing economic growth, social progress, and environmental protections is needed.

The UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is such a strategy. Its sustainable development goals (SDG) framework offers stakeholders, both local and global, powerful tools to address complex challenges of risk, equity, and disaster recovery today.

Disasters don’t discriminate, but neither are they neutral.…Marginalized communities continue to face disproportionate environmental impacts.

The SDGs are particularly valuable now, at a time when equity-driven work is being met with increasing resistance and as climate disasters are on the rise. The 17 individual SDGs are universally relatable objectives that UN member states have adopted and committed to—and they also offer compelling data to support a bold equity agenda.

Historically, data have often been used as tools of oppression. But the SDGs help reverse these traditional power dynamics by disaggregating data demographically, which makes it possible to cross-reference equity outcomes regionally, nationally, and internationally. Further, a central SDG value is “leave no one behind,” mandating equity as central to sustainable development work. Equity-centered work is more difficult to dismiss when it is backed up by data and evidence.

“In the Red”

Disasters don’t discriminate, but neither are they neutral. Due to preexisting disparities, marginalized communities continue to face disproportionate environmental impacts. Disaster risk reduction is critical to mitigating them.

A 2021 report by the UN-affiliated Sustainable Development Solutions Network, In the Red: the US Failure to Deliver on a Promise of Racial Equality, found that majority-White communities in the United States received resources and services at a rate of up to three times higher than other racial groups. The unequal distribution of goods and services impacts a community’s level of disaster preparedness, and its ability to mitigate risk.

According to UNDRR’s risk assessment, rising sea levels could cost the world up to $35 trillion by 2070. Yet most hazardous events start small. Addressing climate-related costs is far more affordable if leaders act in advance rather than waiting for disaster to strike.

Take the case of the January 2025 wildfires in Los Angeles, the largest of which was centered in Altadena, whose residents have been mainly people of color since the 1960s. While fires in the Southern California foothills are nothing new, Altadena’s hazard risk started small and grew over time. A 1994 story republished by Altadena Heritage notes a history of human-caused fires in the San Gabriel Mountains where Altadena is situated going back to the 1880s. The population at this time was largely comprised of White Americans who had migrated from the Midwest.

In 1906, a small house on the outskirts of Altadena caught fire, according to the Los Angeles Herald. A bucket brigade of volunteers formed a line to extinguish the fire. In 1925, 100 fire hydrants were installed in Altadena to lower rising insurance costs. In 1959 a fire in Altadena consumed some 2,400 acres of combustible vegetation and was quelled by 1,300 firefighters, with some brought in from Arizona. In between fires, mudslides frequently filled the canyon.

While the 2025 Eaton fire was certainly the largest fire Altadena has ever faced—consuming over 14,000 acres of land and costing 17 people’s lives—warning signs were evident.

Climate change greatly increased the severity of the recent Los Angeles wildfires. What can be done to reduce the disparate impact from such climate-related disasters? The process of addressing the SDGs, through mechanisms such as the UN’s Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030, offer tools that, if fully implemented, can help mitigate risk—saving both lives and property.

Inspiring Action

International frameworks like the SDGs can be very abstract. How can they inspire meaningful action in low-income communities and communities of color in the United States?

To address this question, ABFE (A Philanthropic Partnership for Black Communities) has developed an interactive curriculum to support cohorts of community foundation leaders from across the country to help them align their existing priorities with the SDGs to advance racial equity. This year, ABFE is partnering with CFLeads and augmenting the curriculum with their Community Leadership framework. The program is supported by a multiyear grant from the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation.

Anticipating concerns about overly technical and complex material, the program first asks participants to consider their current priorities and real-time community concerns in the context of the SDGs. Next, we introduce ABFE’s Responsive Philanthropy in Black Communities (RPBC) framework, using six themes that the RPBC and the SDGs “In the Red” analysis have in common. These are:

- Racial equity is global in nature

- Metrics, benchmarking, and disaggregated data are essential to racial equity work

- Focusing on the least-served is the most effective way to improve overall outcomes

- A systems level approach is needed to understand and overcome structural barriers

- Approaches should apply targeted universalism—that is, setting universal objectives while supporting communities to use tailored approaches to meet them

- Data must inform action, in the form of increased investment, power building, and solidarity

Fortified with an understanding of these frameworks and their relevance today, participants in the cohort will conceive and develop plans for their own place-based initiatives.

More time is needed before we can begin to assess sustained outcomes and meaningful changes. Still, several participant organizations have begun applying the SDG framework. Moreover, some efforts to apply SDGs predate the cohort, and they are encouraging.

Cities and local governments are also well suited to using the SDG framework to advance their existing racial equity priorities.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Applying SDGs in Practice

In 2016, Flint, MI made international news due to lead contamination of its water, the product of a misguided government decision to pursue cheaper water—resulting in devastating impacts that continue to this day.

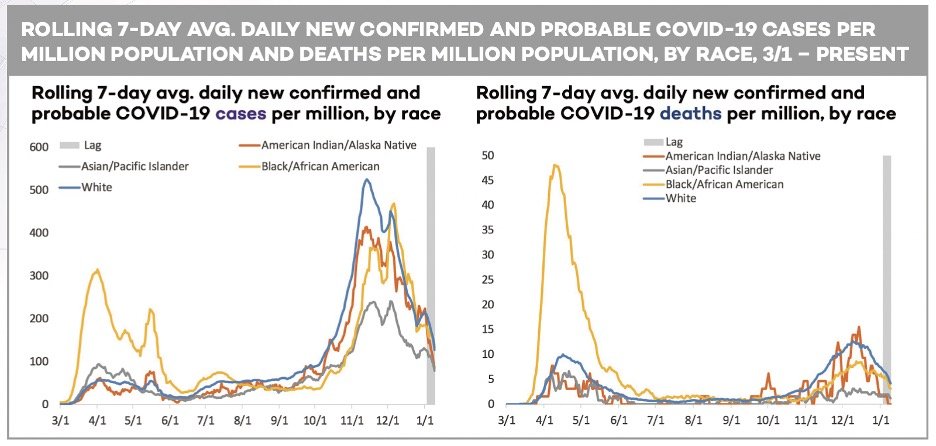

In response, the Community Foundation of Greater Flint prioritized the SDG framework in its work. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the foundation was able to use the SDG framework to track the differential impact of COVID-19 for their grantees and the overall population, quantifying the impact in terms of infection rates, mortality, and other indicators) on Black and Latinx populations.

By applying the universal objectives within Goals 3, 6, and 11 (Good Health and Well-being, Clean Water and Sanitation, and Sustainable Cities and Communities, respectively), the foundation was then able to refocus limited resources to respond to where the performance was lowest. As a result, the foundation was able to show positive results overall, while almost completely eliminating disparities among groups.

The foundation is also embracing the SDG framework and Goal 17 (Partnerships for the Goals) by partnering with Michigan State University’s Social Determinants of Health Solutions Lab. This partnership boosts capacity to collect, track, and interpret data.

Internally, the foundation is using the SDGs to guide its selection of a new institutional data system. The SDGs will also be integral to their upcoming strategic planning process—helping to identify equity priorities, track them, and communicate trends and impact effectively.

A second example is provided by The Cleveland Foundation—the world’s first community foundation, established in 1914. It created the Cleveland Black Futures Fund to strengthen Black communities and Black-led social change organizations.

In 2022, also supported by a Charles Stewart Mott Foundation grant, the Cleveland Foundation held a summit with 17 rooms (one for each SDG goal) to identify synergies and improve internal coordination.

Cities and local governments are also well suited to using the SDG framework to advance their existing racial equity priorities. Goal 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) guides local and regional stakeholders toward creating cities and settlements that are inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable.

A Climate and Health Justice Imperative

“What started out as a natural disaster became a man-made disaster.” This is how President Barack Obama described Hurricane Katrina, referring to both the disparate and devastating impacts on New Orleans’ Black community, and the historical and structural inequity that created the conditions for devastation.

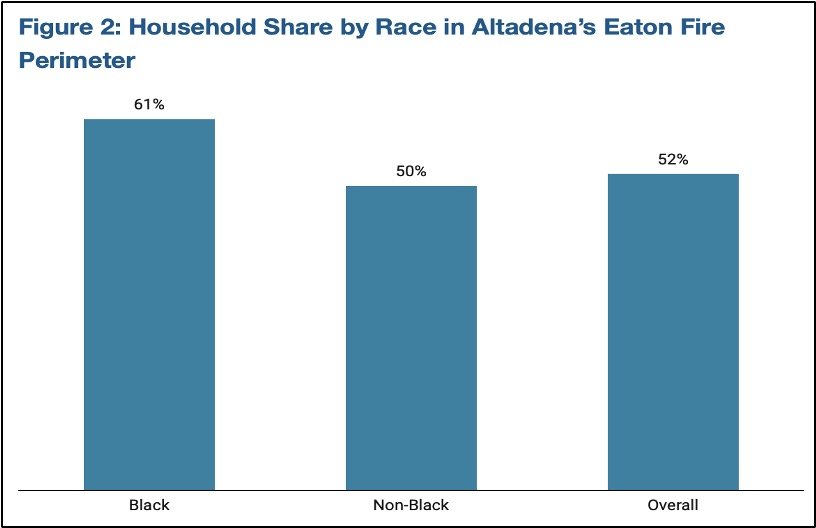

Something similar can be said about the wildfires that ravaged Los Angeles in January, destroying a disproportionate number of homes and businesses in the historically Black neighborhood of Altadena. Altadena is home to a large concentration of Black homeowners, due in part to of redlining dating back to the 1930s.

The growing global climate crisis speaks to the need for new approaches.

Redlining is a race-based exclusionary tactic that was used by the federal government and banks to deny access to home ownership primarily to Black families. This practice barred many Black homeowners and renters from integrating White neighborhoods.

Altadena’s aging and already declining Black population means that this community will have more difficulty recovering and rebuilding, be more vulnerable to predatory lending during that process, and with reduced assets struggle more to build generational wealth, which is closely correlated with positive financial and health outcomes.

The challenges ahead are significant. The cohorts that we are developing to apply SDGs to community resilience and equity are just getting started, and it is too soon to offer concrete results. Nonetheless, the growing global climate crisis speaks to the need for new approaches.

What we know for sure is that wildfires and superstorms are becoming familiar events, and the disparate social and public health impacts of climate change are becoming more visible. It is increasingly clear that to respond effectively, we must, as the saying goes, both think globally and act locally. In this way, we can begin to identify root causes and develop effective responses that advance equity in our communities.