The Mississippi State Penitentiary, better known as Parchman Farm, is the state’s oldest prison. Constructed in 1901, it is modeled in many ways after a slave plantation. In the early years of the prison, under the convict leasing system, prisoners were forced to perform grueling tasks like picking cotton and building tunnels with dynamite.

In the 1960s, over 300 Freedom Riders were arrested and sent to Parchman as they attempted to challenge segregation laws across the country. Forced to work on chain gangs, they saw firsthand how brutal the conditions at the prisons were.

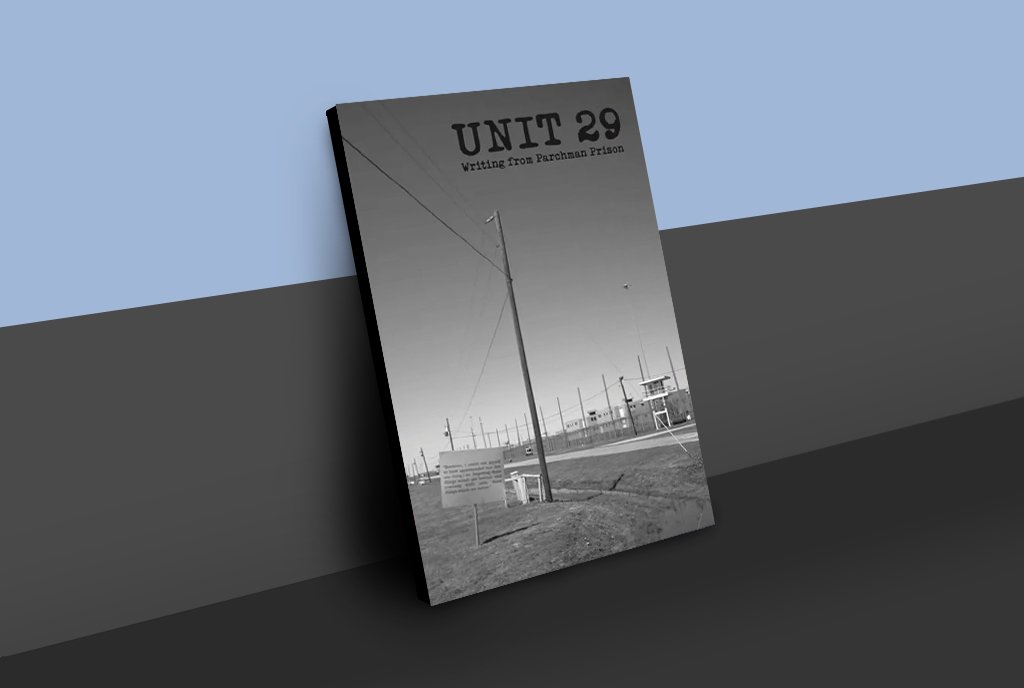

In recent years, Parchman, particularly Unit 29, has become the site of riots as those incarcerated there have protested inhumane living conditions like severe heat and lack of water. Much of this was documented in the 2023 documentary Exposing Parchman, produced by rapper Jay Z.

The increased awareness of the conditions faced by those living in Parchman led to most of Unit 29 closing in 2022—though part of it is still in use.

Against this backdrop, the written work of over 30 incarcerated men at Parchman’s Unit 29 was released in 2024 as a book titled Unit 29: Writing from Parchman Prison.

The Potential of Writing

The men featured in the book had taken a creative writing class taught by Louis Bourgeois, the executive director of the Mississippi Prison Writes Initiative, a nonprofit that aims to teach writing skills to those incarcerated in the state. Unit 29 is the fourth collection from the initiative.

Bourgeois held his first workshops in 2014 after taking over executive responsibilities of Vox Press, a nonprofit with a mission to publish marginalized groups and individuals, support emerging artists, and teach creative writing. Bourgeois said it made sense to try to publish the writings of incarcerated people—even though that had never been done before in the state.

“I contacted Parchman, and they said they would have no issues setting up a workshop to cultivate writing,” Bourgeois said in an interview with NPQ. “From that, the whole thing grew. Another facility that found out about us asked us to come there, and from there, we ended up in several different facilities teaching these classes. The origins are quite simple, but it has run into something of real importance.”

Bourgeois said the men featured in the book were deeply inspired by poet Etheridge Knight.

“[W]e can argue all day about how justice should be administered, but this is not a humane situation.”

Born in Corinth, MS, Knight served in the Korean War, where he was injured. This injury led to an addiction, and ultimately, in 1960, he was convicted of armed robbery and sentenced to eight years in prison. While in prison, he found poetry as an outlet to express himself and find a new life. In 1968, he released his first book of poems, Poems from Prison. The back cover read, “I died in Korea from a shrapnel wound, and narcotics resurrected me. I died in 1960 from a prison sentence, and poetry brought me back to life.”

The idea behind Unit 29 came to be when Bourgeois was teaching a class in Unit 31, another wing in the prison. When the pandemic hit, there was a growing tension in the prison without air conditioning and packed bunk-bed cells. Given deadly riots before the full onset of the pandemic at the end of 2019, Bourgeois said the warden thought the writing class might help ease the stress.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Bourgeois described Unit 29 by noting that it is the largest unit at Parchman, broken up into three sections: one is an open pod, another is for death row inmates, and another is a segregated ward where people are isolated in their cells most of the time.

Eventually, Bourgeois said he was able to teach in the classroom, but at first he had to go cell to cell, teaching people individually.

“I did have students who stuck with me the whole way, but oftentimes you get there and a student I’d been working with for weeks, if not months at a time, was suddenly gone due to a transfer or a death,” Bourgeois said. “There was kind of a high fatality rate back there, which is exemplified somewhat in the book.”

Inhumane Conditions

While teaching the class, Bourgeois found it difficult to disconnect from the prison conditions he saw around him. Although he had taught in Mississippi prisons before, teaching this particular class was intense.

The conditions at Unit 29, Bourgeois noted, were hideous, and the general atmosphere was total chaos—not a healthy place. Smoking is now legal in Mississippi prisons; the fumes fill the atmosphere when you walk in. The incarcerated men also use fire as a form of protest, sometimes lighting a fire in the middle of the zone if they are not fed on time, for instance. And because of how smoke rises, he pointed out, you can barely breathe by the time you get to the second floor.

For some, writing in and of itself is a chance at a better life.

“It’s a very unhealthy environment, and we can argue all day about how justice should be administered, but this is not a humane situation. I’m glad we wrote the book because I think that comes across in the book. I think the experiences back there were translated accurately,” Bourgeois said.

Throughout the book, the men take time to reflect on some of the failures that led to their incarceration. They also describe their living conditions on the inside and write about what they hope their life might look like outside of prison. Although those serving life sentences or on death row are well aware they might never see that life. For some, writing in and of itself is a chance at a better life.

“With this book, my goal was to try and get people to see that all humans should be given another chance.…[I]t’s never too late for a human being to change.”

Such was the case for Nathan Sumrall, who is currently serving life in prison.

First incarcerated in 2009, Sumrall spent 10 years in solitary confinement before being released back to the general prison population in 2023. Throughout his time, he has lost friends to suicide and has dealt with suicidal thoughts himself. One bright spot of his incarceration, he said, has been the writing class.

“My goal was to try and get people to see that all humans should be given another chance,” Sumrall said in a statement to NPQ, “and that it’s never too late for a human being to change.”