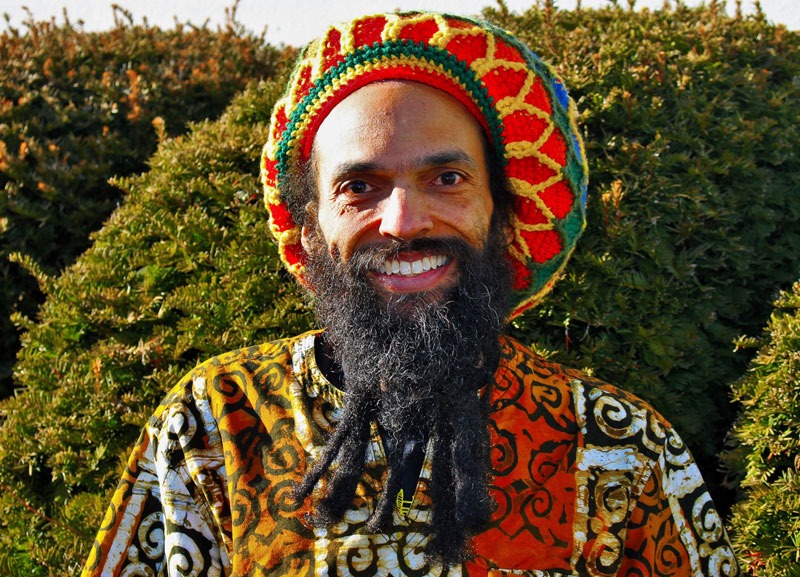

“We built this moment together. The community’s fingerprint is in throughout (the market),” Amaha Sellassie, president of the Gem City Market (GCM) board and co-executive director of Co-op Dayton, told the Dayton Daily News two weeks before the official grand opening of the co-op market. A sign of the co-op’s high profile: A few days before the opening, comedian Dave Chapelle, who lives 20 miles to the east in Yellow Springs, came by to offer his support.

The West Dayton neighborhood store is the first full-service grocer the neighborhood has seen in a decade. On May 12th, opening day, Aliah Williamson of local television station WDTN reported, “Located on Salem Avenue, GCM is the first store in the area in almost a decade and one of the first models of its kind. Inside the store is a health clinic, teaching kitchen, community room, and coffee shop accessible to anyone in the community.”

Any time a new food co-op opens is important for its community, but GCM is more than a community-owned grocery store. As Kenya Baker, community engagement director for Co-op Dayton, the nonprofit organization that incubated the co-op, points out, it’s “not only a grocery store, but it is a movement.”

The movement that would ultimately feed into the co-op organizing effort, as Co-op Dayton’s executive director Lela Klein explains, began on August 5, 2014, when John Crawford III, a 22-year-old Black man, was shot and killed by a police officer in a Walmart store in nearby Beavercreek, nine miles southeast of Dayton. Crawford was walking down the aisle, talking on his cellphone and carrying an air rifle on sale at the store. A white customer subsequently called 911. A video shows the officer responding to the call, shooting at Crawford before Crawford even had a chance to respond.

The shooting occurred just four days before Michael Brown was killed by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri. As in Ferguson, the grand jury failed to indict the police officer responsible. As in Ferguson, prosecutors seemed more inclined to defend the officers than prosecute them. (Six years later, the city of Beavercreek agreed in a settlement to pay Crawford’s family $1.7 million without admitting guilt.)

The August 2014 shooting was captured on Walmart surveillance video and large-scale community protests began shortly afterward. “We all met each other through that,” Klein relates. “Looking back, it was the way we came together that was really special.” Baker observes that because “members of the community, different ethnic groups, religious backgrounds” organized around the protests. This created fertile ground for broader community-building work.

A Public Health Map Spurs Action

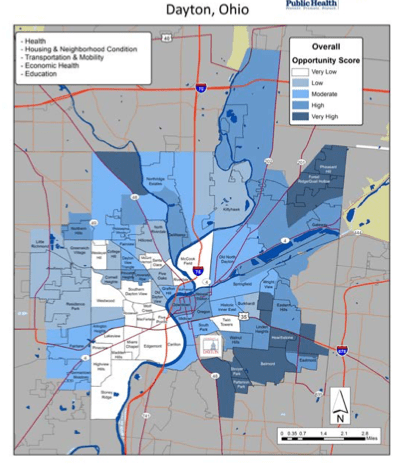

Yogi Berra, the late baseball great known for his many sayings, noted, “You can observe a lot just by watching.” Certainly, this has proven true in Dayton. As Baker explains, it was a public health map that helped spur co-op organizing. Back in February 2015, six months after the police shooting, Baker recalls, “out came an opportunity map, which outlined the opportunities for food, health care, jobs, education, transportation—the major pillars of life.” The map, depicted below, used dark blue to show great opportunity and lighter blue and white shading to show low opportunity. Black communities, she observes, “showed the palest of colors.”

Erica Bruton, who Baker describes as a “young budding politician,” had worked since 2010 as a legislative aide for the Dayton City Commission. Bruton saw in the map an opportunity for the community to organize; as Baker describes it, Bruton started to “galvanize” residents, which was not that hard to do in an already mobilized community.

As Baker elaborates, after a series of meetings, a consensus emerged among Dayton activists that “food would be the best route” to community empowerment. The group began to explore a co-op model. The vision was to “create a hybrid store that was worker-owned and community-member-owned—a unique hybrid co-op in the urban core.” It was an idea, Baker concedes, that was “practically untested.”

As Klein mentioned at last month’s virtual Up & Coming food co-op conference, the neighborhood the co-op serves is 80 percent African American, with a median household income of $28,000. About a third of neighborhood residents depend on SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) or similar federal food benefits. There had been no full-service grocery store in West Dayton since the neighborhood Kroger store closed in 2009 at the height of the Great Recession.

Klein, like Baker, lifted up Bruton’s role, calling Bruton “the original organizer” of the effort. In particular, Klein notes the combination of community organizing and institutional support has been critical. As Klein puts it, “The groundwork that was raised in 2014 and 2015. We had raised the issue of food deserts.” And this meant, Klein says, that major funders took the co-op development effort seriously.

If the group had tried in 2013 or 2014, Klein says “people would’ve been dismissive.” But by 2015, “because there was so much community concern, when we popped up with the institutions, they were ready for somebody to come up with a solution.” Klein adds, “We had support from the city from minute one. From the county. From our local bipartisan legislators.”

All told, the co-op raised $5.5 million from a range of partners, including family foundations, the Dayton Foundation, a New Market Tax Credit allocation, and local hospitals, who saw the co-op as a way to address the social determinants of health. These funds covered building and equipment costs. Additionally, the co-op raised about $500,000 in member equity and $1 million in debt from an Ohio-based community development financial institution (CDFI) for operations. When GCM opened, it received Facebook support messages from the state’s two US senators, Rob Portman (R) and Sherrod Brown (D), as well as the state’s Republican governor, Mike DeWine.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Collaboration, Klein noted in her conference presentation last month, has been GCM’s “superpower” throughout. This included conducting a traditional capital campaign backed by Tony Hall, a former ambassador and congressional representative from Dayton. But it also has included deep organizing and widespread community partnerships.

Sellassie made a similar observation on another panel at the same conference, estimating that GCM had as many as 90 partnerships with outside organizations. As for community organizing, Sellassie noted that, “For Gem City Market, from the name of the market to our mission statement to our architectural design, the community has been throughout. We were highly participatory.” Sellassie conceded that engaging in these community-based processes “took a little longer, and it gets a little stressful at times, but it is more authentic.” And, he adds, it also is critical for ensuring the community feels a true sense of ownership in the market.

Klein provides some of the details involved. About 400 people voted on the store’s name, she explains, adding, “Our architect had office hours at the library. Surveys. Focus groups. Community meetings. Door knocking. House parties. Everything. We were very intentional about that.”

Learning from Greensboro

In 2016, a food co-op called the Renaissance Community Cooperative, or RCC, opened in a Black neighborhood in Greensboro, North Carolina. It was unique in its design and was widely celebrated for boosting food access in a low-income, food desert community. The effort garnered national attention, but in early 2019 the co-op was forced to close its doors. Afterward, the Fund for Democratic Communities, a local private foundation that had backed the effort, carefully documented the lessons they learned. And these lessons have been taken to heart by the Dayton co-op organizers.

Sellassie noted that GCM organizers are “direct beneficiaries of Renaissance.” Klein also emphasizes this: “We are so grateful for the wisdom and openness of the Renaissance folks. They have been so honest and self-reflective… we really benefit from that.”

One lesson, Klein says, is the importance of neighborhood memberships. Often with new food co-ops, having 1,000 members signed up before the store opens is seen as a sign of success. RCC had 1,500. But in hindsight, it was not enough. As Klein explains, many of those 1,500 people bought co-op memberships out of solidarity but did not live in the store’s neighborhood, making them less-than-regular shoppers. Klein adds, “When we had about 1,500 members, we found the same thing—we weren’t meeting our goal. We were hovering around 40 percent in our immediate neighborhood. We had an initial goal of 2,000 members. Once we looked at the data, we set a new goal of 2,000 members in the trade area.” Now, as the store opens, there are 4,300 members, of whom 53 percent are in the trade area.

Memberships in the co-op cost $100, but the co-op worked with partners to subsidize membership for those who could not afford that sum. Low-income members pay $10. The co-op also boosts membership by doing “50/50” matches, where local partners, often area hospitals, pay half the membership fee.

Another lesson was to respect market studies, a message that was reinforced by the Food Co-op Initiative, a nonprofit that advises startups nationwide. The original vision for GCM was to set up the market where an old market had failed, as RCC had done. As Klein explains, “There was a Kroger that was closed in 2009. It was still vacant in 2015. Our initial idea was to open in that location. We did market studies that showed that would not be a feasible location.” Instead, the group sited the market in a place that was “closer to downtown, further north, a better location.”

A third lesson concerns management. How do you hire a person who knows co-ops, the grocery industry, and relates well to the community? Answer: unless you are extraordinarily lucky, you don’t. What GCM has done instead, Klein notes, is “hire the best candidate and with a lot of soft skills and leadership capability who might not have deep grocery or co-op knowledge” and then worked with Columniate, a national organization of food co-op consultants, to codesign customized training. Klein adds that the co-op intentionally had a different manager for the construction phase than for operations, recognizing the two require different skill sets.

Is this enough? Klein is cautious. She notes that in its first two weeks, the co-op’s performance has exceeded projections—a good sign—but it is still early days.

A New Cooperative Design

The GCM co-op is not only unique in terms of its mission and community, but also in its structure and design. The ownership of the market, notes Klein, will be held 70 percent by worker members (the co-op is expected to employ 26 people, who will become members after a year’s tenure) and 30 percent by community members. Board membership will ultimately consist of five worker members, three community members, and one representative from Co-op Dayton, the nonprofit incubator behind the project.

Even the grocery store itself is different than your typical retail grocer. While the building occupies 15,000 square feet, the retail space is roughly 8,000 square feet. As for the remaining space, as Sellassie explains, in addition to the market itself, “We have a teaching kitchen, a health clinic, and a community room all inside of it.”

These resources, Klein notes, will not only provide needed services, but help sustain community support. “Partners are occupying the space with us; it’s theirs. They really own it,” Klein explains. These rooms, Klein says, will host afterschool snack programs, yoga classes, free book giveaways for children, cooking classes, and a smoking cessation program. Klein adds that the store will have two COVID vaccine clinics in the coming week. GCM partners with a grassroots nonprofit to manage the spaces so they don’t become a distraction for store operations.

A Broader Community and Vision

GCM is by far the largest co-op organizing effort in Dayton, but not the only one. Patterned after a similar effort to develop union co-ops in Cincinnati and inspired by the Mondragón cooperatives in Spain, GCM is but one spoke in a broader range of efforts being developed by Co-op Dayton. As Baker explains, these businesses and programs include the Unified Power community land trust, which aims to develop a community-owned building next to GCM, and 937 Delivers, a driver-owned delivery service that serves as a community-based alternative to Uber Eats. The nonprofit hub also supports other projects, including Westside Makerspace (a worker-owned coworking space); Design to Build, a group of architects and engineers that is doing predevelopment work for Unified Power; and TRIBE (Trauma & Resiliency Informed Birth Education), a group of doulas.

At the Up & Coming conference, Sellassie spoke to GCM’s broader vision of a Black renaissance in Dayton and beyond. Co-ops, he emphasized, “are really about learning how to practice participatory democracy at its core.” He added: “We get so stuck. We had 40,000 residents in West Dayton and no full-service grocery store. Some of us accepted that as being OK. Other parts of the community have two or three grocery stores in a mile radius. Why not us? [We are reimagining] what we deserve and, not waiting for Superman, building it ourselves. To me, that is the catalyst and power that Black co-ops and food co-ops in particular have, as we are developing this renaissance in our communities.”