February 27, 2014; Civil Society

How can this be? It looks like some philanthropists in the UK don’t think they ought to be emulating the U.S. approach toward incentivizing the charitable giving of wealthy people. Given the top ranking of the U.S. in the annual World Giving Index, it must be a mistake. Those people in the old country must want to be like us, right?

Apparently not. Rhodri Davies, the policy manager at the Charities Aid Foundation and the author of CAF’s new report, “Give Me a Break: Why the UK Should not Aspire to a ‘US-Style’ Culture of Charitable Giving,” thinks that UK policymakers obsess too much about how charitable giving there lags behind ours.

Davies points out a number of contrasts between the systems of the UK and the United States to explain the differences. For example, he suggests that the U.S. has “one charitable tax relief” mechanism, compared to the “UK’s raft of separate schemes.” This isn’t quite true, as most U.S. states have their own state-level tax incentives, sometimes for specific charitable activities such as education and neighborhood development, and even the federal tax code contains additional tax incentives. However, there’s probably nothing in the UK that comes close to the U.S.’s federal charitable deduction. Nonetheless, the complexity of the UK’s charitable incentives is seen as confusing by donors and charities and warranting simplification.

Others suggest that the UK should be doing more to cultivate a culture of giving for the wealthy in which the rich are expected to give. Michael O’Neill, the chief executive of an organization called Stewardship, notes that the U.S. culture of giving begins with nonprofit board members: “In the U.S., there is a very clear expectation that trustees give, and find others to do so,” he said, “but in the UK I have sat on boards where they don’t.” O’Neill may have a slightly rose-colored tint to his glasses when thinking about the giving and fundraising of U.S. board members, but the expectation is often there, even if unfulfilled.

However, a more fundamental issue may be the structure and function of UK government. Davies indicates that the U.S. welfare state is much less well developed than the UK’s, particularly because of the American commitment to limited government, creating “a fertile space for philanthropically funded programmes.” In other words, government there delivers many of the services and programs that might come from charity and philanthropy in the United States.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Davies further suggests that there are “features of the much-vaunted U.S. philanthropic system that, on closer inspection, might not be all that appealing,” such as the charitable deduction that is biased toward high-income taxpayers, the disproportionate amounts of charitable giving that go to religion and to higher education, and the lack of evidence requirements for much giving that creates “a high risk of dishonesty.”

As described on the Charities Aid Foundation website, “While there are clearly things the UK can learn from the U.S., we must be careful not to assume that everything that works in the U.S. will work here. There are features of the U.S. system that we cannot replicate, and features that we wouldn’t want to replicate even if we could.”

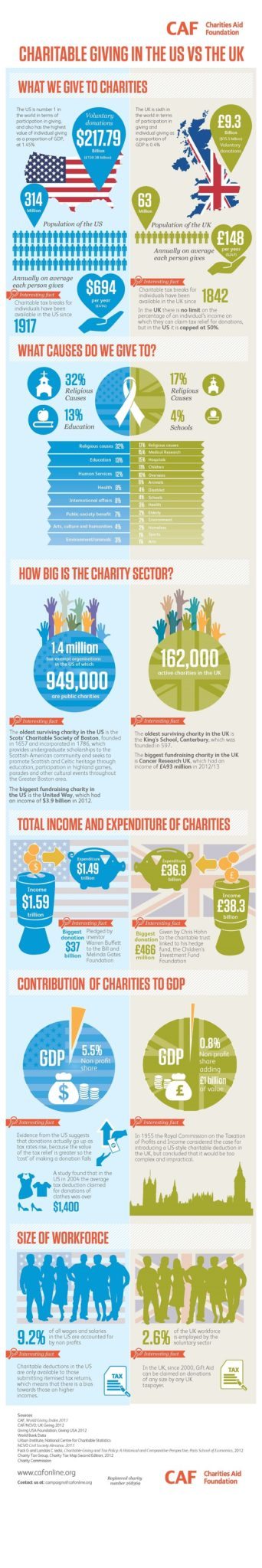

The report is worth a close read, but particularly interesting is an accompanying infographic comparing the U.S. and UK systems:

Particularly interesting items from the infographic are the following:

- Thirty-two percent of charitable giving in the U.S. goes to religion, compared to 17 percent in the UK.

- Education is 13 percent of U.S. charitable giving, giving compared to four percent in the UK.

- The oldest public charity in the U.S. was established in 1657 in Boston; in the UK, the oldest surviving charity was established in 597.

The infographic doesn’t reveal how much the two governmental systems spend on items like education, the homeless, and health, and it doesn’t show how much the government loses as tax revenues in return for the charitable giving incentives offered to donors.—Rick Cohen