March 29, 2019; Kansas City Star

The next mayor of Kansas City, Missouri, is facing a potential sea change in the way the municipality looks at tax incentives for large property development. Activists for the Coalition for Kansas City Economic Development Reform have put together a ballot proposition that will go before voters in June to impose a 50 percent limit on the amount of property taxes the city can abate to incentivize developers to build.

“We definitely would like to see less, at this point, luxury high rises and hotels and more projects that are for your average workforce-type person,” said Jan Parks, a spokeswoman for the Coalition.

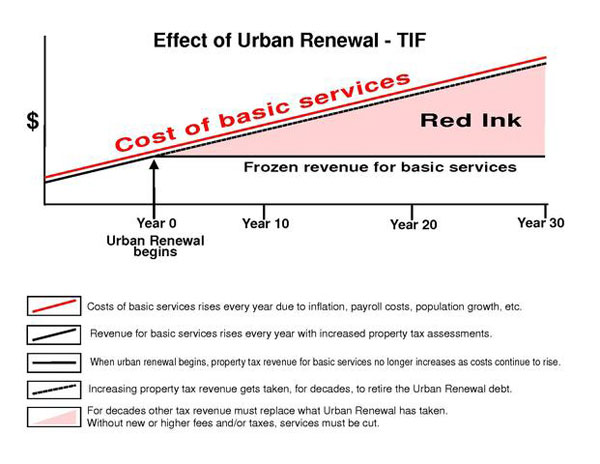

Tax Increment Financing arrangements (TIF) are generally long-term agreements used by the city to encourage development in blighted areas that would not otherwise be feasible. These arrangements use future property and other taxes generated by new development to pay for infrastructure and other improvement costs critical to new development. Specifically, through a TIF, a city borrows against an anticipated increase in tax collections for a specified period (typically between 15 and 30 years). There is risk in this arrangement—you still have to pay even if development fails—but even if the increase does occur, schools and other public services may lack resources, because the increased taxes must pay back the bonds used to finance the development.

Activists call TIF welfare for the rich that takes resources away from other public institutions such as schools. A recent $13.2 million plan to move architecture firm BNIM into a warehouse owned by Shirley Helzberg, a wealthy developer and local philanthropist, inspired a public outcry and an initiative petition to reverse approval of the project. BNIM had applied for a 23-year TIF worth $5.2 million in abatements in what critics claimed was not a blighted area. BNIM ultimately canceled the project before the petition could be voted on.

Most of the 11 candidates running for mayor oppose the measure. Many of them fear that tax abatement caps will stall development everywhere.

A key question is whether TIF subsidies are effective at stimulating economic activity. According to Scholars Strategy Network, on average, they are not. From their 2017 study:

Overall, our analysis finds the level of economic activity in tax-increment financing areas was not discernably greater than the levels in initially similar areas where the policy was not used. In other words, the development in tax-increment financing areas unfolded as we would have expected even if the program was absent. In Kansas City, specifically, the estimated impact of this financing scheme across all instances was very close to zero, which suggests that this city’s program has been ineffective in promoting incremental business development.

Other studies by the St Louis Development Corporation, the East West Gateway Council of Governments, the Upjohn Institute of Employment Research, and the University of Missouri-Kansas City have all concluded that TIF financing does not drive job creation, neighborhood investment, or economic development.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

So, why continue with TIF funded development at all? Are there quality-of-life benefits that can arise from the use of tax abated development financing?

In June 2018, Kansas City celebrated the redevelopment of the Linwood Shopping Center with the opening of the Lipari Brothers Sun Fresh Market. According to the Kansas City Economic Development Corporation, a 2016 Tax Increment Financing Plan enabled the Linwood Shopping Centers nearly $15 million renovation that alleviated “a food desert” in a major East Side corridor. The project was heavily backed by the city, which saw an opportunity to change the character of an entire neighborhood.

Mayor Sly James said, at the beginning of construction in 2017, “If we want to really make a foothold and show we’re making progress on the East Side, this was one of those early visible symbols that had to change.” And Don Maxwell, the previous owner of the site, said during the groundbreaking ceremony, “It’s a ghetto. We’re getting ready to turn it into a gold mine.”

But a look back at the history of the site shows exactly why NPQ has always opposed tax abatements. As was reported in the Kansas City Sentinel:

In January 1991, the Kansas City Star described Maxwell, the president of Community Development Corp., (CDC) as the “developer of the highly successful Linwood Shopping Center at Linwood Boulevard and Prospect Avenue.” Some $5.5 million in public dollars had been invested in that “success.” Maxwell had big plans that would “transform” the inner city.

By 1992, one of Maxwell’s companies was not repaying money that it had borrowed, and the Linwood site was not generating enough funds to repay its loans. In 1993, the city was purportedly providing additional funds to Maxwell because of cash flow issues at the site. In March 1996, Maxwell was reportedly being pursued for $500,000 in defaulted SBA loans, and by November 2009, the Linwood property had gone into receivership. Move forward to in May 2015, and Mayor Sly James has “announced plans to purchase property at the Linwood Shopping Center from Linwood Shopping Center Initiative, LLC, an entity managed by none other than Don Maxwell who had somehow gotten hold of the property again in 2014. In 2016, the city completed the deal.”

So, when Don Maxwell called the site a ghetto to be turned into a gold mine, one wonders: Was he referring to a “gold mine,” or “gold,” as in “mine?”

Tax abatements rarely work, and as the Linwood Shopping Center shows, we can sometimes forget incentivized projects until they come around the bend again, their tired engines tooting the same old horns.—Eric Fullilove