Click here to download this article as it appears in the magazine, with accompanying artwork.

Editors’ Note: This article comes from the Summer 2021 edition of the Nonprofit Quarterly, “The World We Want: In Search of New Economic Paradigms.”

Last summer, millions of people mobilized worldwide to demand change to the policing system that continues to brutalize and murder Black people with little to no consequence. The massive protests have led to a period of reckoning of systemic racism in the United States. Suddenly, many white-led organizations and white individuals have begun to take a much greater interest in the history and experience of people of color. Books about racial inequality have been flying off the shelves. Diversity and inclusion consultants are in high demand. Many nonprofits have felt pressure to make statements about their commitment to the movement for Black lives.1

At the root of this fight for racial justice is the demand to undo the systemic oppression Black people face, and demand reparations to Black people for the harms caused by slavery and ongoing and current racist policies and practices. At the root is also the demand to undo the systemic oppression Indigenous peoples face, and demand reparations to Indigenous peoples for the genocide and other ongoing and current racist policies and practices perpetuated by white settlers.

Reparations is one part of the process of restoring justice for the land theft, genocide, and enslavement committed in the spirit of capitalism, because the generational privilege is still real and the harm to our communities and peoples persists. For Indigenous peoples across the globe, the Land Back movement is at the center of this fight for reparations. Today, over a quarter of Indigenous people in the United States—1.4 million—live below the poverty line;2 and we are still shouldering the burden of yet another pandemic that has only widened the educational, health, and economic disparities that already existed. These inequalities are not by accident; they are by design—the result of continued systematic racism and the coordinated erasure of our existence by this country’s most powerful institutions. Even the studies that examine all such socioeconomic dimensions leave out Indigenous people, which further contributes to the erasure of our issues and needs. There is a real effort to keep Indigenous people invisible.

The collective consciousness that emerged over the past year is focused on creating transformational systems centered in racial, economic, climate, and health justice, and there are critical roles to play and allyship to put into action for philanthropists, elected officials, business owners, nonprofit leaders, and individuals toward this effort. There is also a slower-paced but growing recognition that those closest to the pain need to be in charge of the solutions.

For those who have benefited from white supremacy, support for the Land Back movement can take many forms, including finding ways big and small to pay reparations, divesting from oppressive and exploitative systems, and making direct investments that support Indigenous self-determination.

Land Back and Its Origins3

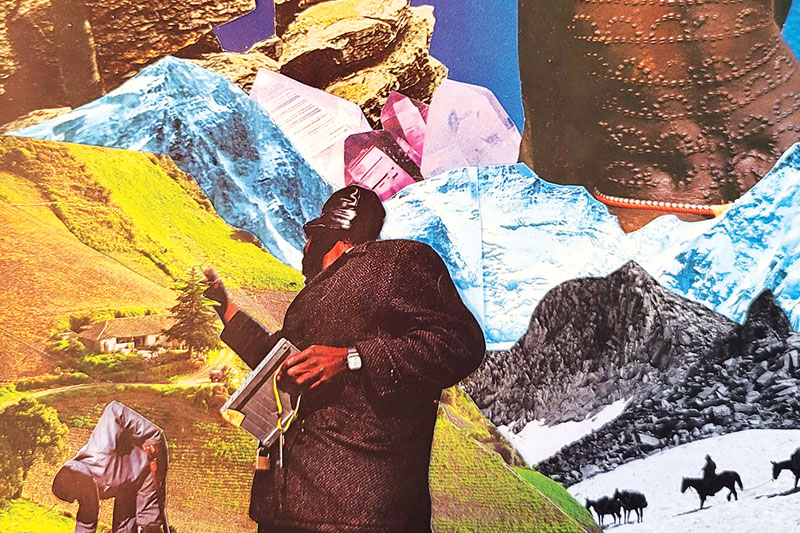

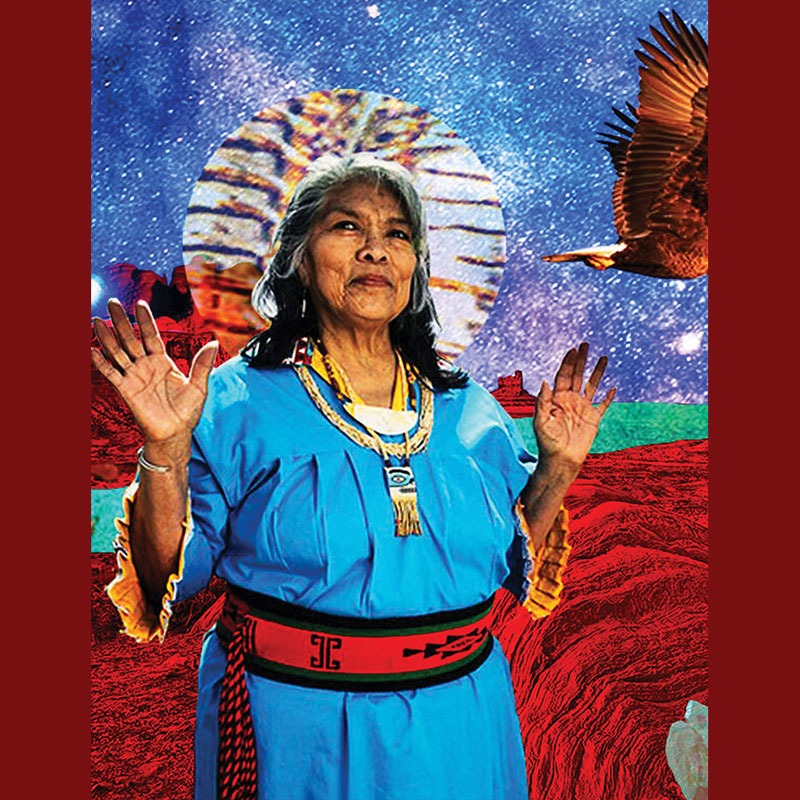

The concept of Land Back, let alone its practices, can be a struggle for non-Indigenous (and even at times for Indigenous) people to understand. Fundamentally, Land Back is the intersectional movement for racial justice by Indigenous peoples, with the end goal of having our lands returned to Indigenous stewardship. Land Back addresses the root of colonization—the theft of Indigenous lands (including their destruction through resource extraction), the violence committed against Indigenous peoples to build capitalism across the country, and the effects that our communities still experience today. The movement for Land Back began over a decade ago. No single group owns or controls the movement, which has spread throughout Turtle Island—the Indigenous name for the lands of North and Central America—and surrounding island Nations. The phrase land back emerged from culture bearers and artisans popularizing the idea through artwork.4 After ten years of organizing, our movement is becoming visible to people in the United States and Canada.

Like Black Lives Matter, Land Back aims to unite many other narratives and provides understanding of myriad issues—in this case facing Indigenous peoples—clearly and accessibly for both those within and outside our communities. Land Back is about reclaiming Indigenous spheres of influence and sovereignty. It is about extending our values to result in better stewardship of ecological, political, and economic systems. Land Back also harmonizes well with the political discourse on reparations and land-centered issues for our Black relatives.

Land Back needs to happen so that all other aspects of Indigenous livelihood can return with it. As a metanarrative, Land Back can serve as a multi-issue and long-term approach for movement-building work to unify Indigenous peoples. The lack of an umbrella for the myriad social, economic, and environmental crises facing Indigenous peoples is one of the biggest obstacles to our collective liberation. Therefore, we need to invest to build capacity and self-determination. Grassroots organizations are often underinvested in and subject to the bureaucracy of the same systemic structures that caused the harm in the first place; to transform and shift the power balance back to oppressed peoples, Indigenous movements must be able to mobilize in multiple domains and sectors.

Today, we believe that Land Back is the most expedient way to support our self-determination, because we understand that (1) increasing visibility by itself is not the answer, because we could lose this moment over time, and (2) nonprofits can kill movements, so we must position this work to be generational, not bound to any one organization, and adaptable to the changing sociopolitical dynamics around us. Under this unifying and organizing metanarrative around Land Back, many voices and movements can become one.

Roots Back to the Doctrine of Discovery

The basis for stealing Indigenous lands was rooted in the “Doctrine of Discovery,” which comprised a series of religious decrees by the Catholic Church that established legal, spiritual, and political justification for seizure of land not inhabited by Christians. The Doctrine of Discovery impacted Indigenous peoples worldwide, encouraging explorers, conquistadors, and settlers from the Western world to colonize lands previously inhabited by autonomous Indigenous peoples. In the United States, the Doctrine of Discovery fueled “Manifest Destiny”—the settler notion that God gifted lands in America to Christians alone, and that it is the responsibility of said Christians to take over lands wrongly occupied by the “merciless Indian savages.”5

The Doctrine of Discovery also binds us together with our Black relatives, many of whom are the descendants of enslaved African peoples stolen by European traders to build the national economy of this country. Reparations are about righting the injustices and continued harm experienced by those hurt most by the founding of this nation.

We will not attempt here to truncate centuries of resulting federal policies, actions, and the socioeconomic impacts on Indigenous and Black peoples. Our main points are (1) that the United States has been a perpetrator of genocide and land theft; and (2) that while it has many different political, legal, and economic levers to move toward justice (because it cannot rectify history), it fails to take urgent national action time and time again to both end the abuse by and transition from the country’s racist laws, policies, and practices.

Four Demands of the Indigenous Land Back Movement

For hundreds of years, the federal government has violated its own treaties and not provided the economic compensation codified in its contracts with Native Nation governments for use of our lands and resources. In the Indigenous context, reparations are not just about financial restitution but upholding the “supreme Law of the Land” and following through on federal trust (and debt) obligations. Consider this: The United States signed nearly 400 treaties and broke nearly all of them. The restitution we are talking about here would be in the trillions of dollars—and this is only taking into account economic compensation and not the other promises made and not kept.6

What many do not understand is that colonization today is still steeped in violence against Indigenous peoples and is still driven by reasons of economy and greed. Other injustices—whether perpetuated on our homelands, in cities, in schools, in foster care, in bank lobbies, or in prisons—are rooted in the violent theft of our lands and natural resources. The colonial tactics develop over time, but the overarching strategy is the same, and the system is still gamed as oppressor and oppressed.

Even existing laws that attempt to preserve Indigenous rights are not effective. Although we have multiple treaties in place guaranteeing the right to free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) before anyone enters our land, those treaties are rarely respected—as can be seen by the continued illegal operation of the Dakota Access Pipeline and Line 3 on sacred Indigenous land.

The core of the Land Back movement consists of four straightforward demands that address the systemic changes and physical and financial reparations needed:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

- Return all public lands back to Indigenous hands.

- Dismantle the structures that forcibly removed us from our lands and continue to keep our peoples oppressed.

- Defund white supremacy and the mechanisms and systems that enforce it and that disconnect us from stewardship of the land, including the police, the military, border patrol, and ICE.

- Move from an era of consultation into a new era of policy around free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC), as specified in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.7

The first two demands are dependent on the last two being met, and all are intertwined. Free, prior, and informed consent means we are truly consulted about who can enter our land, and what is done to it—and that when we say no, the response is to respect our decision and stay away.

The constant overriding of our right to FPIC came to a head last summer, resulting in a peaceful demonstration by Indigenous land defenders on July 3, 2020, in response to a political rally being held at Mount Rushmore Hills, which required consent by Lakota peoples under multiple treaties. When we defended our rightful land, we were met with force by the local police department and the National Guard, and 21 protestors were arrested and faced spurious charges. So long as elected officials freely violate both federal and international law and rely on militarized police forces to back them up, we will not truly have ownership over our lands.

The economic benefits of FPIC being respected are far-reaching. When Indigenous people have a real say in what happens on our lands, we institute sustainable practices around food, water, education, healthcare, housing, and more—counter to the destructive ones employed by current developers of the land. We build systems based on the health and well-being of people and the planet, which will continue to be upheld for generations to come and won’t disappear with a drop in the stock market or the change of a U.S. president.

Reparations in the Context of an Indigenous Land Back Movement

There is not a one-size-fits-all strategy for reparations for Native Nations or Indigenous peoples. Reparations can take the form of national park lands being returned to Native Nation governments, obtaining FPIC in economic development projects, land trusts to return lands to tribes and in some cases individuals, direct grantmaking to Indigenous communities and organizations, investing in physical infrastructure on Tribal lands, and more.

While the case for reparations leans heavily on national policy, there is also a case for philanthropy, as it is both a product and driver of wealth inequality. Ironically, philanthropy often reinforces economic exploitation and extraction by forcing grantees to operate within the rigid rules of white supremacy. It is an enlightening exercise to dive into the history of your local and national foundations to identify their sources of wealth and where their current endowment originated: the blood, sweat, and tears of Indigenous and Black peoples.

Being a concrete part of the push for reparations begins with decolonizing our minds, but we cannot sit quietly in reflection while taking no action in the meantime. Leaders of nonprofits, private companies, elected officials, and philanthropists must apply historical analysis and recognize the reality of Black, Indigenous, and other people of color today. Decisions to repair generations of harm cannot be made in a vacuum; they must be made in partnership with communities every step of the way.

We have the solutions and strategies to get there, but we are looking to the current holders of power to redistribute their wealth, resources, and decision-making to move this work forward.

Our Call to Action

As Indigenous peoples, we need to reclaim—and in some cases redesign—our governance systems, the systemic expressions of sovereignty, the ways in which we relate to one another, and the ways in which we relate to our lands. This is essential to successfully retaking our rightful lands and creating a world that is grounded in equity and justice for all peoples and the planet.

For our allies, here are some action steps that you can take:

- Pay rent. This can be done on an individual basis by setting up a relationship with the Native Nation’s government on the lands you occupy, as over 15,000 and counting have done with the Duwamish Nation in Seattle, Washington, under the banner of Real Rent.8

- Contribute to land trusts. Some nonprofit organizations acquire land so as to protect it and, in some cases, return it to Indigenous peoples. Contributions via a voluntary land tax are one way to fund land buyback. This example is especially powerful in urban areas, in terms of creating a presence for Indigenous peoples. An example of this strategy in action can be found with the Sogorea Te’ Land Trust in Oakland, California.9

- Support efforts to return national public lands to Indigenous stewardship. There are millions of acres of land across the United States that were illegally seized, in violation of federal law. However, individuals and grassroots organizations have long supported the return of national public lands to Indigenous hands, and we have achieved some victories along the way. In 2020, for example, Congress voted to return 12,000 acres of Chippewa National Forest to the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe in northern Minnesota.10

The Role of Philanthropy

We hope our words spur passion and a few pathways for philanthropy to join and support the Land Back and reparations movement.

There are many resources philanthropy can access. One ally of ours, Resource Generation (a community of young wealthy inheritors committed to the equitable distribution of wealth, land, and power), has developed a Land Reparations and Indigenous Solidarity Toolkit to help donors progress in their journey.11

Philanthropy is both a product of wealth inequality and a driver behind it. The metrics of success for philanthropy are rooted in capitalism and a settler mindset, which means that fights for real liberation are often underresourced and even opposed by foundations.

Nonetheless, philanthropists can support racial justice and the Land Back movement if they give up power and invest money, time, and social capital to support organizers, with no strings attached. Indigenous peoples need to uplift our solutions without a paternalistic eye watching our every move and pulling money the moment our ideas deviate from funder notions of what success looks like.

Of course, philanthropy by itself will not ensure the centering of Indigenous practices needed to build a more resilient world and forge the practices necessary for Indigenous survival and flourishing. We need the federal government to recognize the continued harm being inflicted on us when they side with corporations and use taxpayer money to force us off our rightful land.

We know we’re a long way from our goal.

We recognize that shifting federal mindsets and policies will require pressure through many channels, including media presence, lawsuits, calls-to-action, changing mainstream narratives, electing Indigenous officials, and more. Philanthropy cannot move government on its own, but philanthropists can support activities that will change policy by helping to resource the Land Back movement. In turn, we can shift what the public deems acceptable in terms of the federal government’s relationship with us, and, at long last, begin to restore right relationship to our lands.

Notes

- See, for example, Jeanne Bell and Nonprofit Quarterly, “Beyond the Board Statement: How Can Boards Join the Movement for Racial Justice? (Part One),” Nonprofit Quarterly, June 25, 2020; and Jeanne Bell and Nonprofit Quarterly, “Beyond the Board Statement: How Can Boards Join the Movement for Racial Justice? (Part Two),” Nonprofit Quarterly, July 1, 2020.

- “Fact Sheet: Hunger and Poverty in the Indigenous Community,” Bread for the World, October 1, 2018.

- Nikki A. Pieratos, Sarah S. Manning, and Nick Tilsen, “Land Back: A meta narrative to help indigenous people show up as movement leaders,” Leadership 17, no. 1 (February 2021): 47–61.

- Steve Dubb, “A Vision for Social and Economic Justice Rises in Indian Country,” Nonprofit Quarterly, December 18, 2020.

- Mark Savage, “Native Americans and the Constitution: The Original Understanding,” American Indian Law Review 16, no. 1 (January 1991): 63.

- Rory Taylor, “6 Native leaders on what it would look like if the US kept its promises,” Vox, September 23, 2019.

- United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, United Nations (New York: United Nations, Sept. 13, 2007), 11, 12, 16, 20, 21, 23.

- “Real Rent Duwamish,” Real Rent Duwamish, accessed May 19, 2021.

- Maanvi Singh, “Native American ‘land taxes’: a step on the roadmap for reparations,” The Guardian, December 31, 2019.

- “Government to return 12,000 acres to Leech Lake Ojibwe,” KARE11, December 7, 2020.

- “Land Reparations & Indigenous Solidarity Toolkit,” Resource Generation, accessed May 19, 2021.